In my new book, Lifesavers and Body Snatchers: Medical Care and the Struggle for Survival in the Great War, I explore the evolution in combat among the Canadian Corps and the key role of the medical services that acted, as one 1919 report observed, as a “great machine of healing.” Doctors and nurses faced unimaginable wounds as mangled soldiers were brought into the medical units with exposed brains, shattered bones and punctured organs. Treating these ghastly wounds evolved during the war. Infections were rampant in most wounds, and in the age before antibiotics, surgeons were often forced to cut out great swaths of flesh. Blood transfusions reversed shock and X-rays assisted in locating metal in the body. Both innovations saved lives.

There was a constant process of learning and adaption. With half of all Canadian doctors serving overseas, there was a vibrant culture of lectures and symposiums behind the lines. Slain soldiers were autopsied to provide lessons in how to save the wounded. But my research has revealed an even more shocking story. Canadian doctors were part of an Imperial program whereby they harvested the body parts of killed Canadians. Gas-scarred lungs, shattered femurs and even bullet-riven brains were all removed from bodies. They were stabilized and transported back to England. This was done without informing soldiers’ next of kin. Even more disturbing, and never recounted before in any history book, almost 800 Canadian and British soldiers’ body parts were returned to Canada after the war.

Many of those pathological samples contained evidence of disease and illness. Almost every army up to that point in human history had lost more soldiers to bacteria and viruses than shells and bullets. The medical services on the Western Front reversed that trend, with doctors seeking to prevent disease before it raged through the static armies. In fact, Colonel John Adami, a prewar McGill professor of medicine, wrote, “The great, outstanding feature of the War has been the triumph of preventive medicine.”

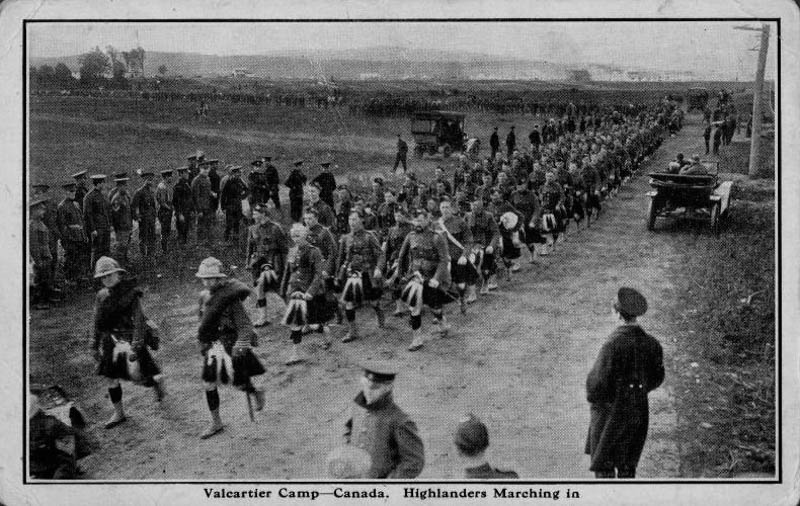

This excerpt presents the important role of the medical officers of the First Contingent in treating the more than 35,000 soldiers who were to arrive at Valcartier Camp in Quebec from late August 1914.

From Lifesavers and Body Snatchers by Tim Cook:

Canadian troops practice shooting Ross rifles during training at Valcartier, Que., in 1914.[Courtesy of Tim Cook ]

If soldiering is rarely glamorous, doctoring in such conditions was often equally mundane.

The Canadian medical services had studied the problem of disease since the South African War, and the destruction of human and animal waste became a priority in preventing sickness and disease. The many latrines at Valcartier were monitored to ensure proper sanitation, with horse manure piled at a distance from water sources and incinerated when possible. The water pumped from the Saint-Charles River along new pipes was frequently tested for cleanliness and chlorinated. If soldiering is rarely glamorous—with drill, marching and occasionally shooting to enliven the drudgery—doctoring in such conditions was often equally mundane. The many foot blisters and weeping sores that were examined and treated sporadically broke the monotony, along with horse kicks and the occasional broken bone from some accident.

An outbreak of cholera, typhus, or typhoid would have been devastating.

A number of tubercular men were identified in the ranks and sent for hospital care in Quebec City, many of them in tears as they were denied going overseas. And while more than a few taunts were directed against the doctors, who were given nicknames like “Doc Feces” or “Lord of the Cough,” the medical services’ enforcement of public health regulations and isolation of sick men safeguarded against an epidemic spreading through the ranks. Such matters were not regularly top of mind for the harried senior officers, but an outbreak of cholera, typhus, or typhoid would have been devastating, and they listened to their medical officers.

Andie Mack, had kept his wooden leg a secret until he was “told to take his trousers down.”

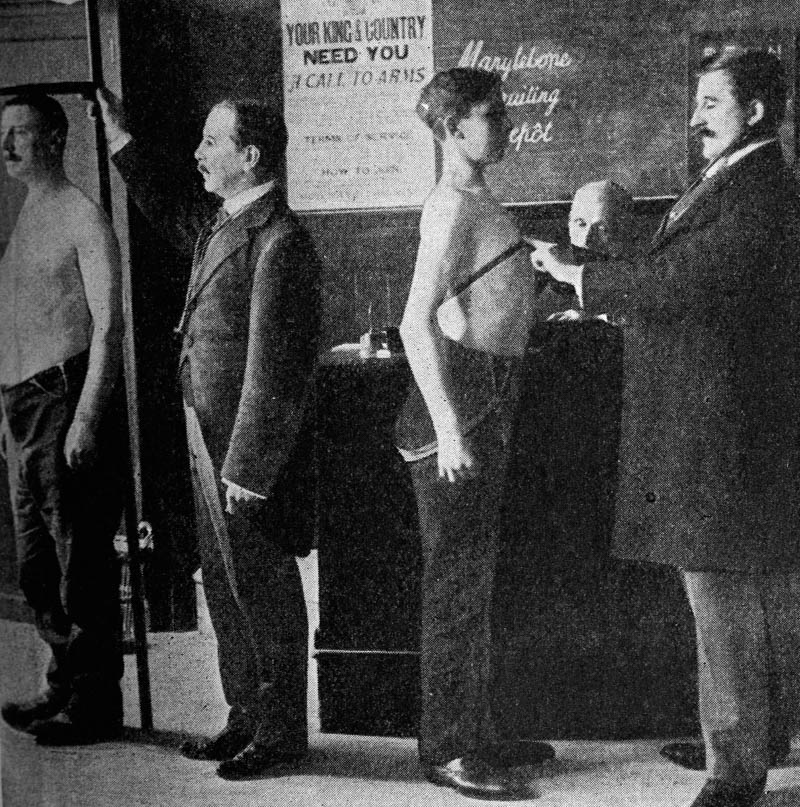

With about 35,000 new soldiers converging on Valcartier, 10,000 beyond what the British had requested as part of the initial force, the medical officers there were instructed to begin a second round of health inspections in order to weed out the ill-suited and unfit, as well as those over 45 or under 19. Thirty medical officers were assigned to the task, with long lines of soldiers snaking away from their examination tents. Like most men, Ernest Davis disliked the process, but although he described his discomfort at being poked and prodded “like so much meat,” he was pleased to make it through.

Not all did, and men with flat feet or poor eyesight were often removed, as were those with more obvious ailments. Captain George Gibson wrote of encountering a man missing a hand who had spent days concealing his wrist in a pant pocket; another soldier, Andie Mack, had kept his wooden leg a secret until he was “told to take his trousers down.” Bad teeth led to some being sent home, even as gap-toothed men protested that they wanted to shoot the enemy, not bite him. Many of the dentally challenged soldiers were accepted a year later when standards were lowered and after military dentists were called in to clear out the mess of broken and missing chompers in men’s mouths.An estimated 100,000 Canadian men were rejected during the course of the war because they could not meet health requirements.

Sunken chests and varicose veins in legs were surprisingly common in many of the malformed recruits who were raised on poor diets that included little dairy or vegetables and who had endured extended bouts of malnourishment. In the first two years of the war, non-white Canadians were usually denied service, as were Indigenous Peoples, although records do not indicate that they were singled out in these examinations. Throughout September, close to 5,000 soldiers were removed from the service, most for medical reasons, making them a part of the estimated 100,000 Canadian men who were rejected during the course of the war because they could not meet health requirements. While this was not a fitness problem faced only by the Canadians, the shameful revelations of unhealthy men would be lamented by social reformers and then employed to launch a new crusade for reforms to aid the impoverished who had been too frail or sickly to serve their country as soldiers.

Fierce debates over vaccination had raged in Canada before the war.

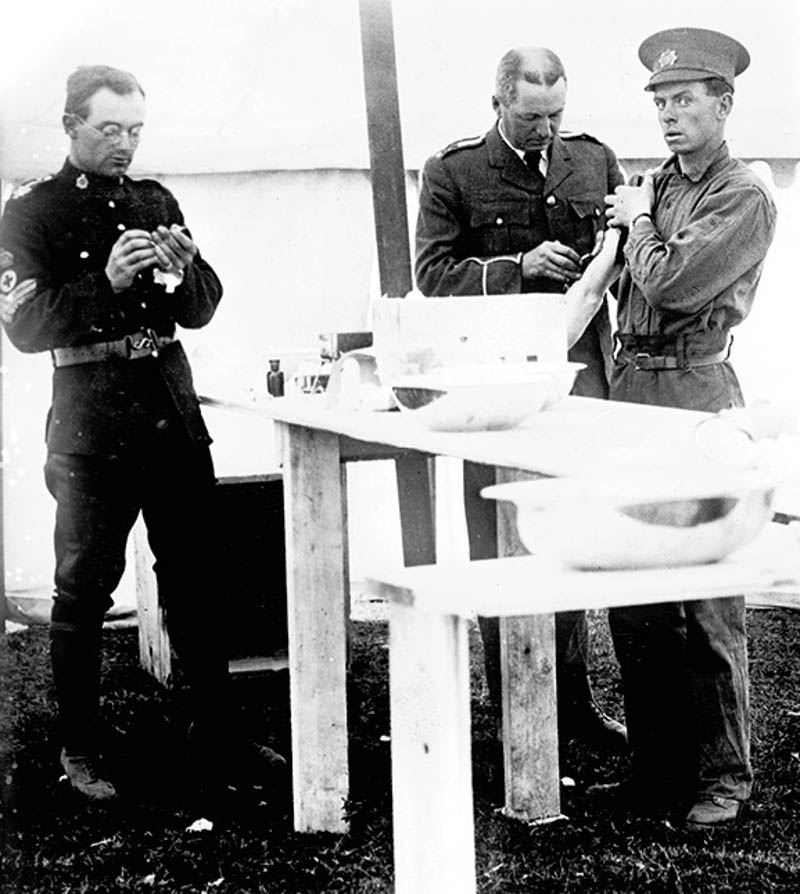

A few men were removed from service because of their refusal to accept inoculation against potential diseases. Fear of the needle, or what was in it, led to their dismissal. Fierce debates over vaccination had raged in Canada before the war, and opponents remained even after the 1885 smallpox outbreak in Montreal that killed thousands. Despite the horror of smallpox, one of the deadliest diseases in human history, those who railed against vaccination to prevent the contagious plague called it a hoax or a government conspiracy to poison children. In this age of evolving medical advances, some Canadians had experienced severe anxiety about what was being injected into their bodies. But the deepening of state intervention through inoculation in the early 20th century, especially in schools, saved lives, and an intense public health campaign was waged to spread positive information about the value of vaccination.

British soldiers found clear-cut evidence for the value of vaccination in saving lives.

There had also been high-profile prewar discussions in Britain over whether to vaccinate soldiers in the British army against their will, which was reported in Canadian medical journals and newspapers. This opposition in Britain led the military authorities to make inoculation voluntary. British soldiers who later campaigned in the Middle East and Gallipoli, with these regions’ inhospitable environments, found clear-cut evidence for the value of vaccination in saving lives. In Canada, Toronto doctor George Nasmith, who served on the Ontario Provincial Board of Health and was appointed as an officer of sanitation despite his diminutive size of four foot six, convinced Minister Hughes to accept the value of vaccination. McGill University’s Lieutenant-Colonel George Adami, one of the most respected doctors of his time, wrote that the soldier who declined the vaccination was to be removed from service: “He was not allowed to endanger the health of his comrades.”

Historian Tim Cook’s latest book explores medical care during the First World War.

[Courtesy of Allen Lane, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited]

—

Excerpted from Lifesavers and Body Snatchers by Tim Cook.

Copyright © 2022 Tim Cook. Published by Allen Lane, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Advertisement