The disastrous Dieppe Raid of Aug. 19, 1942, is most commonly remembered by a grim statistic—the greatest one-day losses sustained by the Canadian Army during the Second World War. There was ample heroism on the beaches. Less well known are the heroics displayed by a small group of men who were captured by the Germans that day but managed to escape. Even when they were decorated for their exploits, the stories were shrouded in wartime secrecy to protect the lives of European helpers and preserve nascent escape organizations.

The soldiers taken prisoner at Dieppe were initially detained in France. Many were hospitalized. Those who weren’t wounded or were only lightly wounded were held at Verneuil, west of Paris, until the end of August, when they were moved to Germany. Not surprisingly, most of the successful escapes took place while the men were still in France. They had to weigh the hazards of travelling through German-occupied France as opposed to moving through the part of the country controlled by a French government (headquartered at Vichy) which was collaborating with the enemy—a distinction that vanished in November 1942 when German forces invaded even that part of the country that had been nominally governed by their Vichy puppet.

Four of the earliest Dieppe prisoners to escape were members of Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal—privates Guy Joly, Conrad Lafleur and Robert Vanier, plus Warrant Officer Lucien Dumais. All managed to escape before being transported to Germany.

The story of Dumais is the best known because of the books he wrote: Un canadien français à Dieppe and The Man Who Went Back, with Hugh Popham. A street-smart reservist even before the war, he proved a brave, even reckless soldier at Dieppe.

While still training in Britain, he attended lectures on escape and evasion. They included advice about approaching civilians when seeking help: not in the morning but at the end of the day. Women in preference to men. Old rather than young. Poor rather than rich. Country people rather than city people. Priests and doctors rather than merchants or shopkeepers. In his books, Dumais describes the atmosphere of fear that permeated France in 1942—particularly fear of neighbours who might report would-be helpers to the Gestapo or collaborating gendarmes. His military haircut and Quebec accent made him as much an object of suspicion as empathy.

Dumais had been wounded at Dieppe, but still resolved to escape. Within 36 hours of capture, he leaped from a moving train at night, followed by two other soldiers—Corporal E.J. Vermette and Private M.P. Cloutier (both Fusiliers Mont-Royal). They had intended to link up by whistling the opening bars of “Un Canadien Errant,” but failed to connect. His two companions were recaptured on Aug. 27 and spent the rest of the war in captivity.

Dumais had intended to make his way to the coast, steal a boat and row his way back to England. He was soon advised by sheltering civilians that this was impossible—too many guards and obstacles, every boat watched—and was persuaded to turn south. By Aug. 24, near Poitiers, he had made contact with an escape organization that consisted chiefly of people in different towns who were linked by family or friendship. Joining this network actually slowed him, as he had to spend several days in various hiding places. He eventually reached Perpignan, near the Mediterranean coast, and from there was evacuated by boat to Gibraltar with about a dozen other escapees. By Oct. 21, he was back in England.

Dumais was awarded a Military Medal. In November 1943, he went back, parachuting into France. He spent months organizing the movement of downed Allied airmen back to Britain—a story outlined in The Man Who Went Back and told in greater detail in Un Canadien français face à la Gestapo. He was commissioned while still in France and awarded a Military Cross.

Two of the members of Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal—Lafleur and Vanier—had been seriously wounded during the battle. The third, Joly, pretended to be ill and was placed in the same hospital as the other two. The trio resolved to escape, but time was running out. On Aug. 24, they were put on a hospital train bound for Germany—15 coaches, 30 beds per coach, and one coach at the end of the train with 15 armed guards.

A single German orderly was assigned to each hospital coach. The man in their coach was either stupid or lazy; they persuaded him to leave the care of the wounded to them. He said, “Gut, gut, Kanada,” gave them some tobacco, and went away. The windows were locked, but Joly, Lafleur and Vanier disposed of the concertina fabric between the coaches and, around midnight, jumped from between the coaches as the train slowed on a gradient east of Amiens. They landed on hard ground, which jolted the two wounded escapees, but they were on their way to freedom.

They were extremely fortunate in making immediate contact with heroic civilians. The first people they approached—a farming couple—promptly took them in, provided food, baths and civilian clothes, photographed them for false documents, and summoned a doctor who dressed their wounds. On Aug. 26, they started their journey, which took them by car to Amiens, by train to Paris and Bourges, on foot to Saint-Germain-des-Bois, by car to Montluçon, and by train to Lyon, which they reached on Sept. 1.

At one point, French gendarmes, hovering between loyalty to Vichy and dislike of the German occupiers, nearly arrested them. At Lyon, they passed from the hands of relative amateurs to a well-organized escape system that took them to Marseilles, Toulouse, Perpignan, through Spain and finally to Gibraltar. By Oct. 5, they were back in Britain.

All three were decorated with the Military Medal. They subsequently declared their willingness to return to France to assist in escape operations. Vanier did so—and narrowly escaped recapture in circumstances that would almost certainly have led to his execution had he been taken. He was awarded a Bar to the MM for his 1943-44 underground activities, as well as a French Croix de Guerre and an American Medal of Freedom. Lafleur also returned to organize escape routes. At one point, when he was about to be taken prisoner, he shot four Germans and escaped again. This necessitated his immediate evacuation back to England. His underground tour brought him a Distinguished Conduct Medal and a Croix de Guerre.

Escape wasn’t the sole province of non-commissioned ranks; three Canadian officers succeeded in escaping in France against overwhelming odds. Captain George Browne (Royal Canadian Artillery), Lieutenant Augustus A. Masson (Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal), and Capt. John Runcie (Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders) all escaped before the enemy could move them to a German camp.

Runcie was the first. He faked an attack of appendicitis, was transferred to a hospital in Paris, and escaped in pajamas through a window on Sept. 5. His subsequent journey was a remarkable feat, for although he enlisted the help of successive French civilians, he didn’t link up with any organized escape group, and had to improvise his transportation and route.

Guarded by German soldiers, Canadian troops are marched through the streets of Dieppe following Operation Jubilee. [LAC/PA-200058]

Warned that the border between occupied and unoccupied France was heavily guarded, he chose to move through occupied territory to reach Spain. At first he travelled by night, but changed his schedule when he discovered that bridges and highway checkpoints were less rigorously guarded in daytime. Most of the trip was on foot, although he received occasional lifts from French truck drivers and on two occasions from German ones. To the Germans, he represented himself as a Basque mechanic, en route home, but to the French he was always candid about his identity. The most difficult part of the trek was two days spent between Bordeaux and Bayonne in a pine forest with no farms and no accessible water—“as bad as the Sahara,” he described it. Using a crude map supplied by a hotel waiter, he managed to enter Spain without a guide.

Masson, wounded in battle on Aug. 19, was held at a camp near Verneuil, where he and other officers were segregated from non-commissioned ranks and interrogated. On Aug. 28, they were put aboard a train for transfer to Germany. East of Paris, Masson squeezed through a window while the train slowed down to pass through a tunnel. This was especially dangerous because the distance between the coach and the tunnel wall was less than half a metre. He quickly linked up with Browne, who had jumped at the same time, and they travelled together with civilian help until Sept. 10, when they were arrested and separated by French police as they tried to cross into the unoccupied zone.

Masson and Browne had similar adventures. Technically interned by Vichy authorities, their situation changed dramatically in November, when the Germans and their Italian allies occupied the territory hitherto governed by the collaborating Vichy regime. On Nov. 27, Masson, detained at Chambarand, was released with other prisoners by a French commandant who abandoned his loyalty to Vichy. Once free, Masson quickly linked up with an escape organization and slipped into Spain. He departed Gibraltar for England on Jan. 21, 1943.

In the meantime, Browne had made another escape but was recaptured and transferred to Chambarand about Nov. 8. However, he was not liberated by the commandant, who in any case was soon replaced by an Italian officer. Prisoners were loaded into two buses on Dec. 7 and taken away. Presumably the destination was Germany. At Moirans, the vehicles stopped close to dusk. PoWs stretched their legs while drivers and guards put water into radiators before starting up again. The guards were boarding by the front door of his bus just as Browne was exiting by the back door. He was missed immediately, but evaded searchers in the gathering darkness. He spent two weeks making his way across southern France, receiving help from some civilians, refused it by others, until he was smuggled into Spain via Andorra. He reached Gibraltar on Jan. 17 and arrived in England on the same day as Masson.

Browne was awarded a Distinguished Service Order; Runcie and Masson received Military Crosses. In all cases involving these escapes, the reasons for the awards were shrouded in wartime secrecy with the minimum of fanfare and no published explanations as to why they had been honoured.

Soldiers of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, the main assault force for Operation Jubilee, were captured by Germans after being pinned down on the beach in the ill-fated Dieppe raid. [CWM/19900076-952]

Escaping from prison camps in Germany itself was far more difficult. Getting “outside the wire” was just the beginning; the greatest difficulty was staying at large in a hostile environment and finding a way out of the country. Three Canadian soldiers managed this task—Pte. John H. Kimberley (Royal Hamilton Light Infantry), Sergeant Seneca MacMullen (Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders) and Cpl. Gustav A. Nelson (The Calgary Regiment (Tank)).

In all three cases, the men had endured months of imprisonment and the humiliation of shackling for weeks. When they finally escaped, it was the culmination of numerous escape attempts.

In March 1943, Kimberley, then held at Stalag 344 near Lamsdorf, exchanged identities with another prisoner and was assigned to a work party employed at Breslau. He eluded his guards and boarded a freight train, only to be discovered in Dresden. Five months later, he escaped again using the same tactics (identity switch for a work party outside the regular camp). He and a companion reached Czechoslovakia and were sheltered by Czech Partisans for three weeks. When they attempted to continue alone (with Switzerland as their goal), they were identified as escapees and interrogated by the Gestapo for a month.

In March 1944, the Canadian PoWs were transferred to Stalag II-D near Stargard. Kimberley escaped again, this time posing as a French civilian in German employ. He reached Stettin (now Szczecin, Poland), on June 2, but discovered he needed something to bribe his way aboard a ship. He returned to Stargard and virtually broke back into the camp to obtain cigarettes that could be used as barter for sugar that in turn might buy co-operation. Just as he was leaving the camp once more, he was arrested and placed in solitary confinement for a month. Despite this, he managed to join another outside work party and escape from it on Aug. 3, 1944. He was back in Stettin the next day.

Three days later, Kimberley succeeded in boarding a Swedish ship where he and another PoW hid in a dry tank. While the ship was passing Dalarö, Sweden, the two fugitives swam ashore and were sent by the local police to Stockholm. Early in September, Kimberly was flown back to Britain. He was awarded a Distinguished Conduct Medal in March 1945.

Nelson was involved in tunneling work at Lamsdorf, but he failed to get outside the wire until he escaped with MacMullen near Teschendorf. The latter had managed to escape twice before but had never been at large for longer than a week. MacMullen and Nelson volunteered for a work party, and although they were lodged in a wire-ringed compound, security was less vigilant than that of the main camp.

On June 9, 1944, having loosened bars on their barracks, cut the wire and eluded patrols, they escaped. They carried papers that identified them as Swedes working in Germany. These forgeries stood up to numerous inspections by occasional police constables and numerous railway agents, guards and inspectors. They reached Swinemünde (now Świnoujście, Poland), on June 11 and found shelter with an underground contact until June 14, when they boarded a ship bound for Sweden. They too were flown back to England and eventually received Distinguished Conduct Medals.

The Dieppe Raid is remembered chiefly as a tragedy and a failure, occasionally justified on dubious grounds of “lessons learned.” The battle itself was marked by great sacrifice and bravery on the part of many Canadians; the aftermath of escape and evasion, though less studied, nevertheless merits inclusion in records of the event.

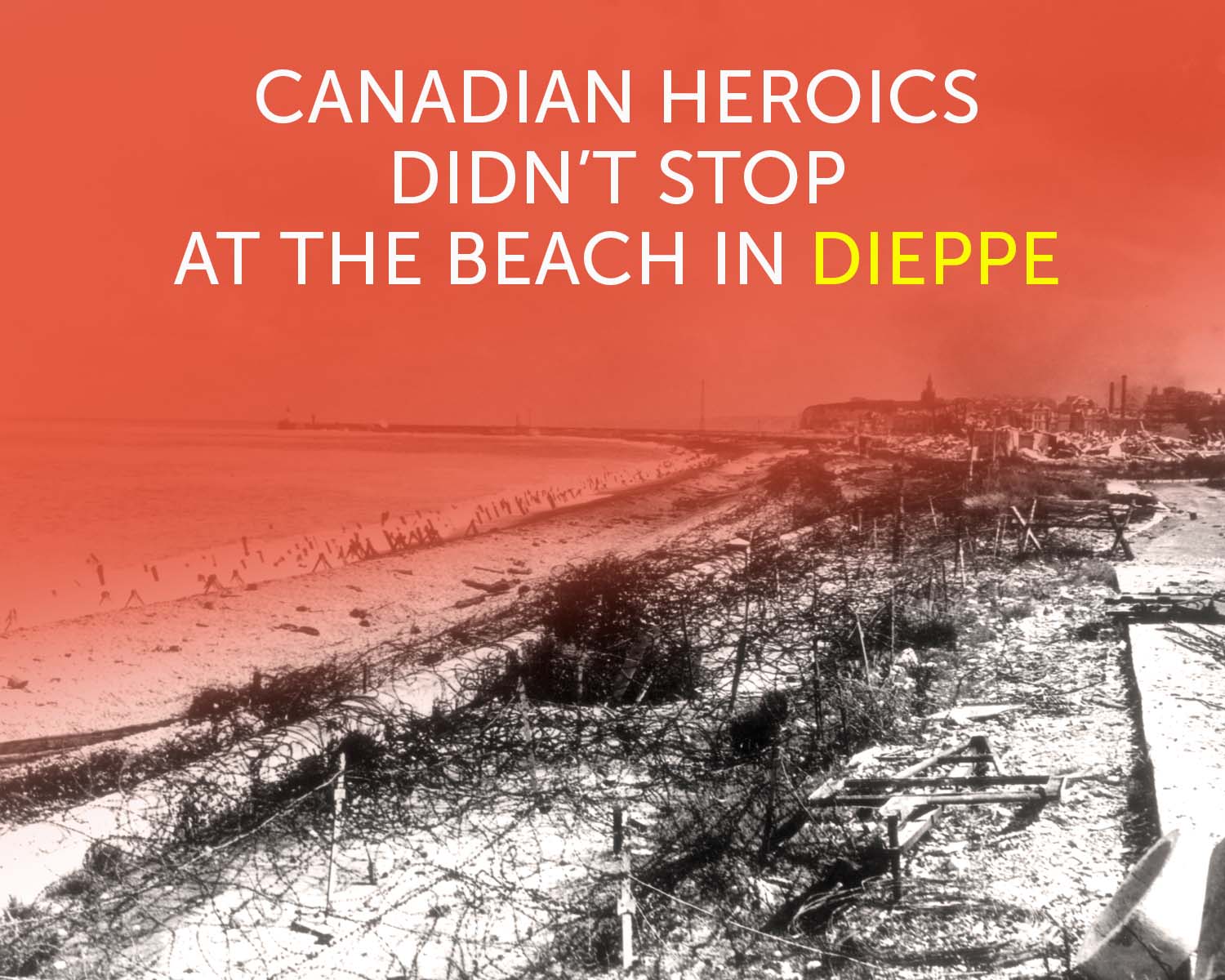

Top Photo: Tangles of barbed wire and anti-tank obstacles fortified the beachfront at Dieppe, France, on Aug. 19, 1942. Of almost 5,000 Canadians in the raid, 907 were killed, 586 were wounded and 1,946 were captured. [Legion Magazine Archives]

Click here to order the WW II Collection today for only $44.95

and receive these three award-winning special issues!

Advertisement