This year marks the 100th anniversary of not only the end of the First World War, but also the extension of the federal suffrage to most Canadian women, a development spearheaded by tenacious Canadian suffragists and abetted by the war itself.

Like the Allies’ victory in November 1918, the Canadian suffragists’ important, but incomplete, victory in January 1918 came after a long, hard struggle. But theirs was a bloodless one. For the most part, it involved petitions to lawmakers, private members’ bills and public education, but not the fiery militant tactics employed by their British counterparts. Led by Emmeline Pankhurst, they would chain themselves to London railings and sometimes resort to bombs and arson.

The Canadian women’s suffrage movement began sprouting clubs across the country in the 1870s, driven by the conviction that women were at a distinct disadvantage because they did not enjoy political equality at every level of government. By the end of the 19th century, the movement was well underway, with groups established in all parts of Canada except in extremely conservative Quebec, where Roman Catholic nationalism reigned.

Not all women favoured the vote for women. Some opposed it outright while others, perhaps most, were indifferent. As for Canadian males, the majority of them probably agreed with British MP Lord George Hamilton, who declared that to “put women on an equality with men is contrary to Heaven’s Act of Parliament, and to the everlasting law of nature and of fact.”

Closer to home, Premier Sir Rodmond Roblin of Manitoba had a more guileful justification for opposing the extension of suffrage. “I think too much of woman,” said Roblin, “to have her entangled in politics. She would be stooping from the pedestal on which she has sat for centuries.”

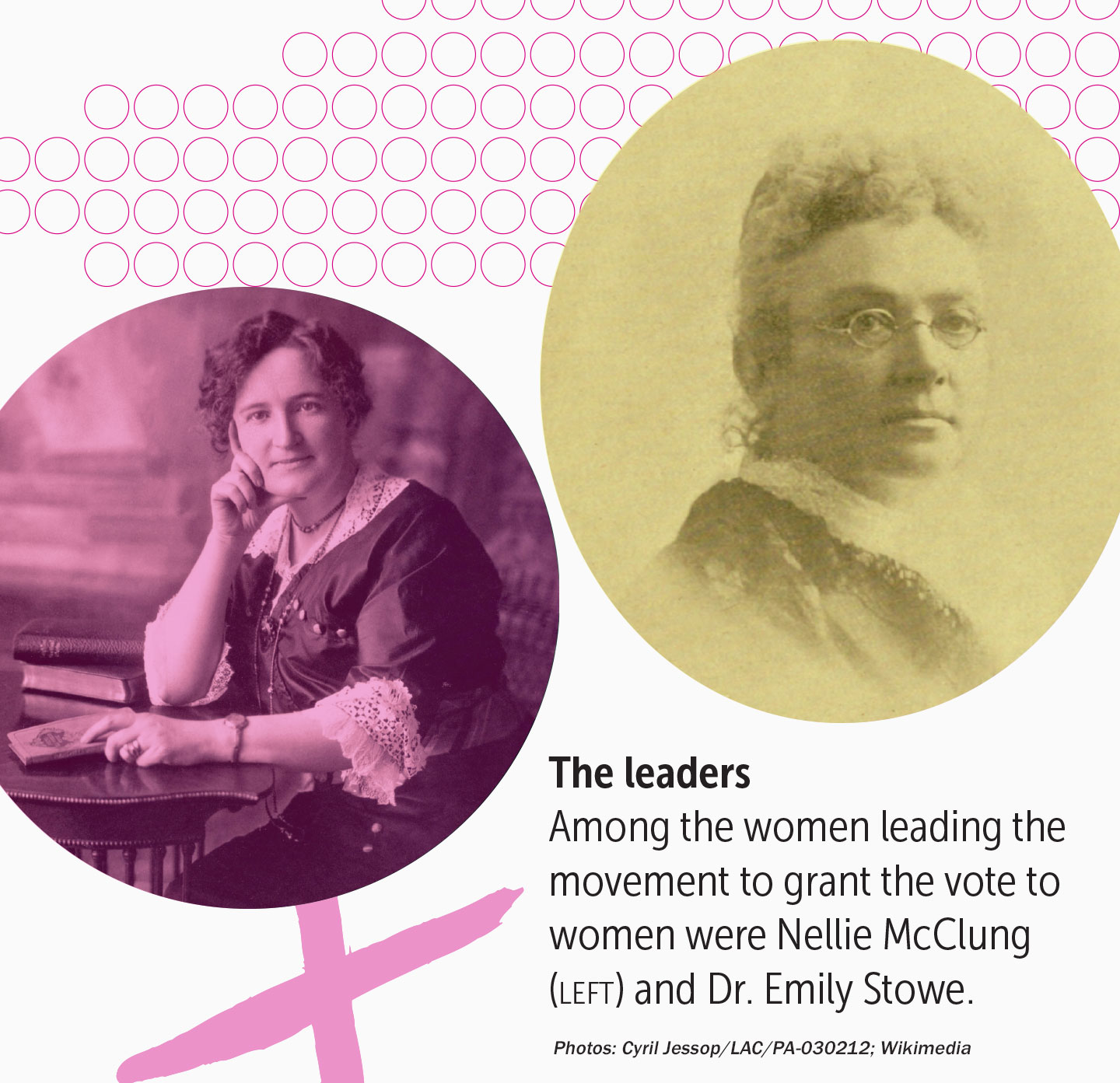

Those who fought for the cause were invariably white, English-speaking members of the well-educated, urban middle class, many of whom belonged to other supportive organizations such as the influential Women’s Christian Temperance Union, which championed suffrage. Among the first suffragists were many female pioneers in the professions such as medicine, where they had encountered discrimination. One of these trailblazers was Canada’s first female physician, Dr. Emily Stowe, who founded the Toronto Women’s Literary Club as a front for suffrage activity. In 1883, it changed its name to the Toronto Women’s Suffrage Association.

Besides campaigning for the vote for women, Canadian suffragists fought for social reform, setting their sights on improved public health, social assistance, workplace safety, child labour, the “Canadianization of immigrants,” and the prohibition of alcohol. In their view, these social issues, particularly “the curse of alcohol,” could only be attacked effectively if women could bring their valuable maternal instincts to bear on them.

Manitoba, the first province to grant the vote to women, was the home of Nellie McClung, Canada’s best-known suffragist. This irrepressible activist believed firmly in the perfectibility of society. But first, certain obstacles had to be removed. One was the demon drink, the other was political inequality. To win the vote for women, she threw herself with gusto into the Manitoba suffrage campaign, as she would later in Alberta.

A mother of five and a popular author and journalist, McClung used her acerbic wit, gift for repartee and organizational skills to full advantage in the fight for female suffrage. This maternal feminist contended that true democracy would be realized only if every adult, regardless of gender, could participate in government. “The time will come, we hope,” she wrote, “when women will be economically free, and mentally and spiritually independent enough to refuse to have their food paid for by men; when women will receive equal pay for equal work, and have all avenues of activity open to them; and will be free to choose their own mates, without shame or indelicacy.”

“Votes for Women” campaigns were erupting in other Canadian cities when McClung and her colleagues led a broad-based suffrage delegation to the Manitoba legislature in Winnipeg on Jan. 27, 1914. In its chamber, the delegation made a formal request to the Manitoba government for voting rights for women. As one of the principal spokespeople, McClung presented the case for female suffrage with wit and irony. A sympathetic report of the speech appeared in the Grain Growers’ Guide.

“There is nothing inherently vicious about politics, and the politician who says politics are corrupt is admitting one of the two things—that he is party to that corruption or that he is unable to prevent it. In either case, we take it that he is flying the white signal of distress and we are willing and even anxious to come over and help him. (Applause and laughter),” it reported.

Assuming his usual paternalistic manner, Premier Roblin pointed to the havoc wrought by the suffragettes in England and cited a crumbling of family life in the United States after women started voting. Women might eventually be granted the vote, but, he hoped, not in his lifetime.

Following this rebuff, McClung and fellow members of the Manitoba Equality League staged a mock parliament in Winnipeg’s packed 1,800-seat Walker Theatre the following day. In the play’s main event, the Prairie activist did such a remarkable job of parodying Roblin’s patronizing speech of the day before that the audience, mostly women, but including some men, broke into gales of laughter. In the words of the Winnipeg Tribune, the event was “the best burlesque ever staged in Winnipeg.”

No doubt, many actions of western suffragists contributed to Manitoba becoming the first Canadian province, on Jan. 28, 1916, to extend the suffrage, but few likely had a greater impact than this suffrage comedy. Manitoba’s example was followed by Saskatchewan (March 14, 1916) and Alberta (April 19, 1916). Ontario and British Columbia were next (1917), then Nova Scotia (1918), New Brunswick (1919), Prince Edward Island (1922), Newfoundland, which was then an independent dominion (1925), and Quebec (1940).

It is not surprising that the newly settled West appeared more receptive to the idea of women’s suffrage. According to historian Veronica Strong-Boag, its openness to female suffrage was partly governed by at least one ignoble consideration: The vote might attract white newcomers who would help to guarantee the displacement of indigenous peoples.

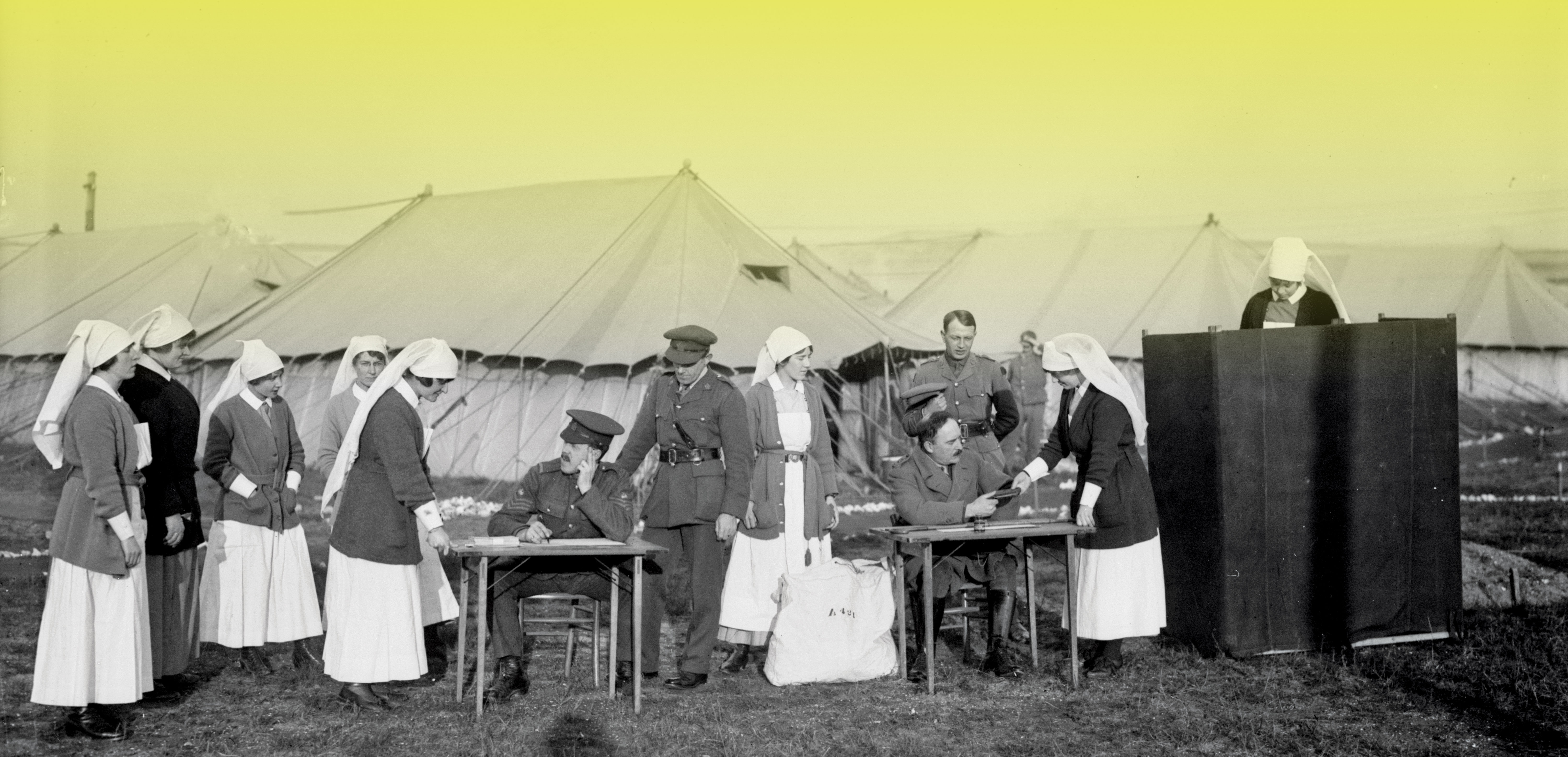

First-time voters: Nursing sisters at a Canadian field hospital in France line up to vote in the 1917 federal election. [William Rider-Rider/DND/LAC/PA-002279]

As for the extension of the federal franchise, it took the First World War to bring it and prohibition about. With female suffrage steaming ahead in the provinces, pressure mounted on the federal government to broaden the federal franchise. For its part, the government recognized that it should acknowledge the tremendous contribution that women were making to the war effort. Thousands of them worked in munitions factories and other war-related industries as well as in banks and offices, which formerly had employed only men.

Ultimately, however, the immediate impulse for widening the federal franchise was political. When the First World War began in 1914, Canadians never dreamed that it would be a long one. Yet in 1917, it was still being waged, with soaring casualties and plummeting enlistments. After returning from a trip to England and France in May 1917, Sir Robert Borden decided that his unpopular Conservative government would have to abandon voluntary enlistment and resort to conscription.

It was a measure sure to inflame passions across the country, particularly in Quebec, which was vehemently opposed to it.

Determined, nevertheless, to introduce it and thereby increase Canadian strength at the front, Borden spearheaded the formation of a coalition Union Government in October 1917. This government and its predecessor introduced two measures that were transparently designed to increase the ranks of pro-conscription voters and help the government win the December 1917 federal election.

The first of these was the Military Voters Act, which enfranchised soldiers under the age of 21 and inadvertently benefited women serving as military nurses in the war effort. According to Elections Canada, those who voted at a field hospital in France in December 1917 were, because of time differences, among the first women to vote in a federal election.

The second law, the Wartime Elections Act, which came into effect on Sept. 20, 1917, disenfranchised citizens of enemy alien birth who had been naturalized after March 31, 1902, and those who were conscientious objectors. But it awarded the vote to mothers, wives and sisters of soldiers. This was an intolerable situation that could not be allowed to persist for long.

As a result, the re-elected Borden government, on March 21, 1918, introduced a bill to provide for universal female suffrage at the federal level. Not surprisingly, it did not receive universal approval. MP Jean-Joseph Denis, for example, declared, “I say that the Holy Scripture, theology, ancient philosophy, Christian philosophy, history, anatomy, physiology, political economy and feminine psychology all seem to indicate that the place of women in this world is not amid the strife of the political arena, but in the home.”

The efforts of Canadian suffragists were finally crowned with partial success when the Act to Confer the Electoral Franchise upon Women received royal assent on May 24, 1918. Thanks to it, most women 21 years of age and older could vote in federal elections. (Exclusions of people of Asian origin and aboriginal peoples would be lifted federally in 1947-48 and 1960, respectively. In 1982, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms guaranteed all citizens over the age of 18 the right to vote.)

Nellie McClung and her fellow suffragists had at last won their long-sought victory.

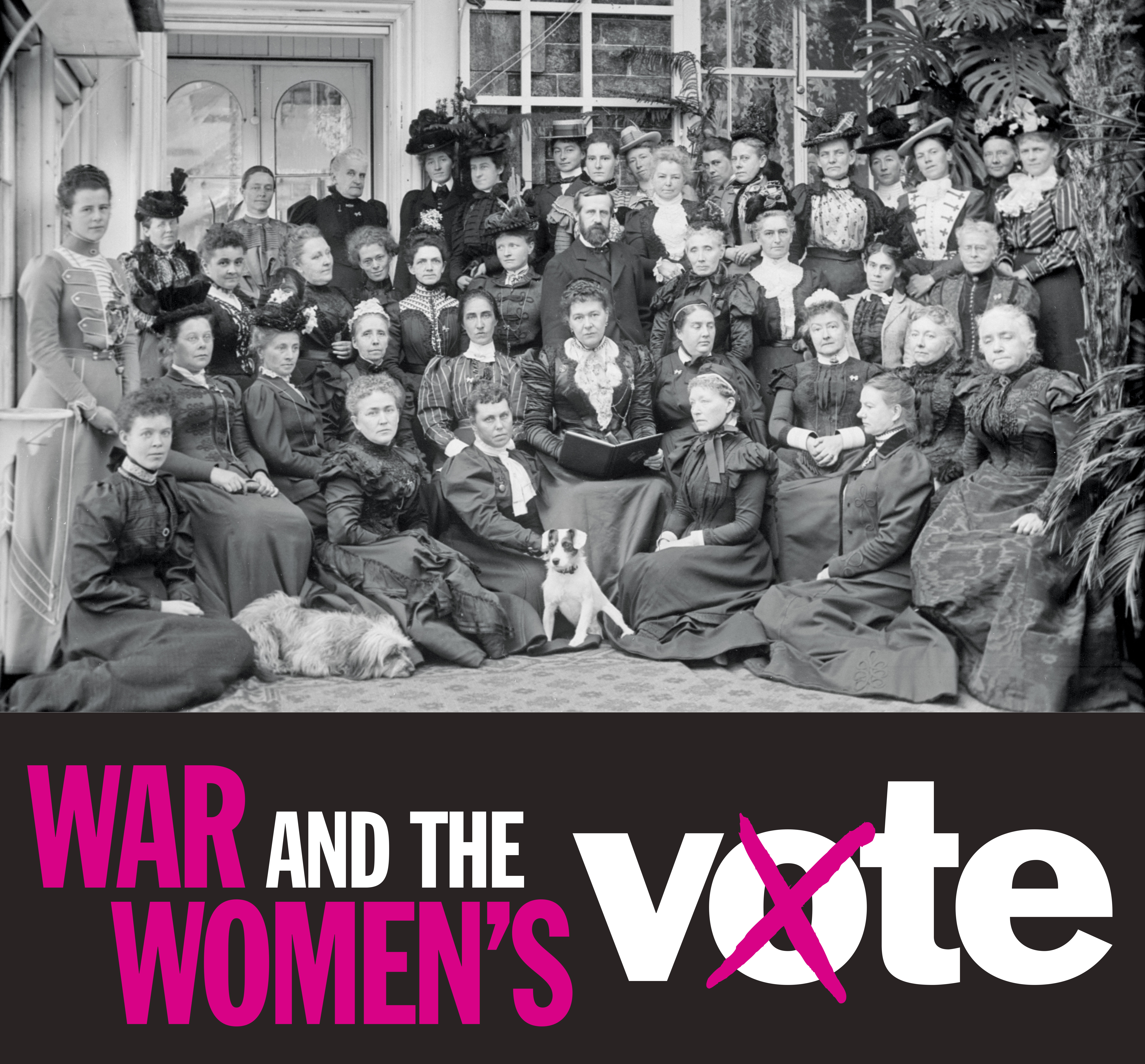

(Top Photo) Making their case: The National Council of Women join the governor general, Lord Aberdeen, and Lady Aberdeen at Rideau Hall in October 1898.

Advertisement