What does the Canadian public think about the treatment of its war veterans?

Do Canadians believe these men and women are getting the benefits and services they deserve?

How familiar is the public with the programs that were created to assist those who have come home after serving their country in some of the most dangerous places on the planet? How satisfied are the veterans themselves with what is offered through Veterans Affairs Canada? Legion Magazine wanted to know and so it commissioned both a scientific national public opinion poll and a readers’ survey. The results, which are printed on the following pages, will surprise you.

In addition to sharing the results with you, we present—in the form of a practical guide—information on veterans financial compensation and services. But first, we begin with a short history.

Click to download the Infographic (PDF)

————————————————————————————————————————————

The Promise Made To Veterans

By Tom MacGregor

As soon as the first casualties began returning home from the First World War it became clear that the federal government had very little experience in dealing with veterans—and even less in dealing with disabled ones.

Neither Canada, nor the world, had ever experienced anything like the mobilization of troops that occurred with the First World War. Out of a country of less than 7.8 million, Canada enlisted 620,000 men and women for war service. Of them, approximately, 66,600 were killed and more than 172,000 were wounded.

Compensation for those who fought in Canada on the Plains of Abraham in 1759, in the War of 1812, the rebellions of 1837, the Fenian Raids and even the Nile Expedition had been somewhat improvised. One of the most popular methods was a grant of land or scrip. Veterans of the Fenian Raids in the 1860s and 1870, for instance, were given 160 acres of land on the Prairies.

In 1931, 160 surviving veterans of the 1885 Northwest Rebellion were awarded $300 each in lieu of scrip they had been entitled to but had never received.

However, giving away parcels of unsettled land was hardly enough to deal with this sudden influx of returning veterans. Indeed, something more had to be done, but what?

In August 1914, Sir Herbert Ames, a wealthy Montreal businessman and member of Parliament, established the Canadian Patriotic Fund. This was a private charity with the governor general as the patron and the federal minister of Finance as the treasurer. Its advertising material urged Canadians “to fight or pay.”

Patriotic funds had existed in Canada for more than 100 years. They accepted donations from individuals and businesses and dispensed money to either the families of the men fighting or provided pensions for those disabled by their service. Each fund would have its own rules for dispensing the money that was gathered.

The Canadian Patriotic Fund was hugely successful at first, raising more than $50 million. It set up a network of volunteers who visited homes and determined the level of need. A wife could receive $5 to $10 a month with $1.50 to $6 for each child.

These volunteers worked as social workers dispensing advice—whether wanted or not—on budgeting, child care, nutrition and personal hygiene. All this was done with a high sense of moral furor with any family deemed to be undeserving dropped from the program without appeal.

This was clearly not enough and the public began to call on the government to take responsibility for the welfare of veterans and their families.

In 1915 the government created the Military Hospitals Commission (MHC) to serve wounded and ill veterans. Buildings were acquired and converted into hospitals. A factory was established in Toronto to produce prosthetics.

The MHC was responsible for those who were returning from the trenches with tuberculosis. Sanatoriums were built or expanded, often in remote locations where the air was thought to be better for a soldier’s recovery.

Those coming back with operational stress injuries were often coldly referred to as shell shocked. Many were sent off to institutions for the mentally ill or disabled.

Pensions were also introduced at this time. The Canadian Board of Pension Commissioners was established in 1916 to set pension rates for returning veterans.

Training courses were developed to help the disabled reintegrate into civilian life and find gainful employment. Those who were physically fit and willing to farm could benefit from land offered through the Soldiers’ Settlement Act of 1917.

In 1918 the Department of Soldiers’ Civil Re-establishment was created to administer the hospitals and medical care for the sick and wounded. It also took responsibility for pensions and training programs. All these were meant to be temporary measures while the soldiers settled back into civilian life and self-sufficiency. But that was not the case for many disabled veterans who would live with their disability for the rest of their lives.

In the postwar period, rumours and faulty information caused a great drop in morale among returning soldiers. The government embarked on an advertising campaign to fight the misinformation. Ads were placed in newspapers to tell soldiers that pension rates would continue to depend on injuries incurred during military service and would not be reduced by the earnings a veteran might make working in industry or elsewhere.

It was during this time that various veterans’ advocacy groups started to form, including the largest of such groups, the Great War Veterans Association (GWVA). The GWVA would eventually join forces with most of these groups in 1926 to form the Canadian Legion of the British Empire Services League.

In reacting to the calls from veterans groups the government passed the Pension Act in 1919. It was to provide compensation for death and disability related to military service during the war and was also intended to facilitate the repatriation of more than 500,000 Canadians who served in the Canadian Expeditionary Force. More than 70,000 of the returning veterans had sustained permanent injuries.

In addition, the Pension Act was to provide for the surviving dependants of the more than 66,600 Canadians who died in the war.

The coverage provided under the act falls under two principles: the insurance principle and the compensation principle.

The insurance principle provides pension coverage 24 hours a day for wartime service. This was later to include service in specially designated Special Duty Areas, usually during peacekeeping operations.

The second principle is the compensation principle which provides pension coverage for disability or death which is directly related to, or permanently worsened by peacetime service factors or events.

The Pension Act also includes a clause that the board—when considering an application—should give the veteran the “benefit of doubt.” Often the most misunderstood part of the Pension Act, benefit of doubt was to recognize that in wartime medical and other records were often poorly kept, misfiled or lost. Often it is difficult or impossible to connect disabilities with particular injuries sustained while serving.

A pension is both recognition of duty to country and compensation for loss. A 2004 study of the Pension Act conducted by Veterans Affairs Canada notes, “apart from providing compensation and support, the [pension] program was established as an expression of national gratitude and recognition for the sacrifice that veterans made on behalf of Canada in the war.”

Eligibility and the amount of a pension were determined by the Board of Commissioners which eventually became the Canadian Pension Commission (CPC). Veterans who were not happy with the decision of the CPC could appeal to a different body, the Veterans Appeal Board.

Once entitlement to a claim is established, then there is the adjudication process which determines the extent of the disability. The extent of disability is expressed as a percentage, with a total disability assessed at 100 per cent. When a pensionable disability is assessed at less than 100 per cent, the pension is proportionally less.

In 2013, a pension for 100 per cent was set at $2,593.32 per month. An assessment of 50 per cent was $1,296.66 while an assessment of 10 per cent was $259.33 per month. Those whose disability is assessed at less than five per cent receive a one-time payment but no pension.

Establishing eligibility put the onus on the applicant, creating an adversarial system. Realizing many veterans would require help navigating through the system, the GWVA, and later the The Royal Canadian Legion, established the Dominion Command Service Bureau with paid service officers to assist veterans with submitting their claims.

The government itself established lawyers within the system in the 1930s to assure veterans that no stone would be left unturned in considering applications.

In many ways the compensation set up for returning veterans of the First World War became a paradigm for other compensation programs developed by government such as unemployment insurance, welfare, Canada Pension Plan and baby bonuses.

When the Second World War started, the government knew it would have to do a better job at re-establishing the returning service personnel than it had done after the First World War. Many government policymakers were themselves First World War veterans and by then, the Legion was a strong voice for veterans.

The Department of Pensions and National Health was split up in 1944 and the separate Department of Veterans Affairs was created. It had sole responsibility for pensions and programs for returning veterans. It is in this period that the original Veterans Charter was created.

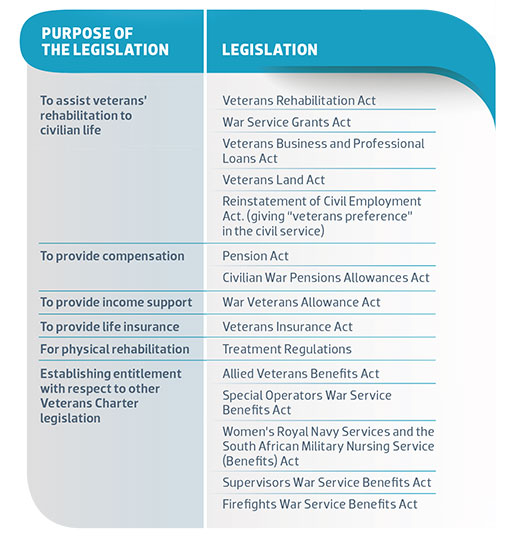

Established in 1946 just after the Second World War, the Veterans Charter is a package of 15 pieces of legislation to help re-establish veterans. Using a chart created by Veterans Affairs Canada, the charter can be broken into categories as follows:

Over the years VAC developed a number of programs to help veterans. These programs are known as the Health Service Line and include long-term care, prescriptions and payment for medical devices such as hearing aids.

Perhaps the most sought-after benefit is the Veterans Independence Program (VIP) which is designed to help aging veterans remain in their homes longer before having to enter a more costly, and less enjoyable, long-term care facility. The VIP provides funding for such services as housekeeping, Meals on Wheels, grounds maintenance and home adaptations, including the installation of ramps and grab bars in the bathroom.

To get these services the veteran must have a disability attributable to military service or be a low-income veteran receiving war veterans allowance. To get a pension, a veteran must have an assessment of a minimum of five per cent. However, even if the disability is assessed at one per cent, the claimant can gain access to the Health Service Line. Getting that assessment is often called the “gateway” to all these services. It should be noted too that it has been a long-standing position of the Legion that frail veterans should be eligible for VIP, regardless of where they served or whether they suffered a disability.

The clients who served in the First World War, the Second World War and the Korean War became the centre of most of VAC’s work for next five or six decades.

In the 1990s, in an attempt to overhaul the system and speed up the time it took to process a claim, VAC delegated responsibility of processing first applications to staff inside the department.

The Canada Pension Commission and the Veterans Appeal Board were abolished and a new quasi-judicial body, the Veterans Review and Appeal Board (VRAB), was created to provide two levels of redress for those unhappy with the initial decision on the first application. A review hearing is the first level of redress and it is the only time in the process when applicants may appear before the decision makers to tell their own story.

The second level of redress is the appeal hearing. It is a second opportunity for the representative, which could be a lawyer, pension advocate or Legion service officer, to make oral or written arguments in support of a claim.

Members of the VRAB who were involved in the review are not enlisted to hear an appeal of the same case. This is to ensure that the case is heard by a second set of ears.

As the number of traditional veterans declined, VAC and the Canadian Armed Forces found they had a rising number of younger veterans of the CAF who had quite different needs. The average age of a veteran being released from the Canadian Armed Forces was 36. Many were struggling to find jobs at an adequate salary and dealing with family stresses. In the 1990s with deployments to places such as Bosnia and Rwanda, veterans were coming home with different, sometimes more complex injuries than those of the Second World War or Korean War.

Consultations began with veterans groups and other stakeholders to “re-imagine” veterans’ benefits. To do this they looked back for inspiration at the original Veterans Charter.

The result was the Canadian Forces Members and Veterans Re-establishment and Compensation Act, commonly referred to as the New Veterans Charter (NVC). Unlike the Pension Act, which was designed to help someone live permanently with a disability, the New Veterans Charter put an emphasis on wellness. Access to rehabilitation services and financial service was based more on need than on being able to establish a gateway to the Health Services Line.

The New Veterans Charter provides a tax-free payment—up to $298,587.97 in 2013—in compensation for loss of income and non-economic issues like pain and suffering. Originally this was a lump-sum payment but recent changes have given veterans the choice of receiving a lump sum, an annual regular sum or a combination of both. It provides financial benefits to supplement monthly income, to replace loss of earning and to compensate for the reduced capacity to save for retirement.

There are rehabilitation programs to restore health and vocational training to help a disabled veteran find suitable employment. Other features include case management, career transition service and family support.

Most importantly of all, the government has promised the New Veterans Charter would be a living document which would change as inequities and gaps were found in the system. However, government programs do not change easily. The New Veterans Charter showed gaps within the first year. One of the first points that needed to be addressed was the disability award which came as a lump-sum payment. It took five years for the government to make the first round of changes in 2011 which included giving more flexibility to the disability award which could be taken as a lump sum, spread out over annual payments or a combination of both.

Three years after the first changes were introduced, veterans groups are pushing hard for the government to make more changes. The Legion is among veterans groups calling on the new minister of Veterans Affairs, Julian Fantino, to conduct a thorough review of the financial compensation in the NVC. More attention needs to be paid to the families of wounded soldiers, sailors and airmen and women. As well, the 2013 federal budget specifically called upon the minister and his department to work with the Legion in addressing pressing issues to deal with funeral and burial regulations which have adjusted the survivor estate exemption of $12,015 since 1995 and do not grant eligibility to low-income Canadian Armed Forces veterans. Much work is still to be done.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the start of the First World War. For the federal government there has been 100 years of learning how to look after veterans and their families. While veterans advocates will always be looking at ways to improve the system, a system is there to guarantee that a grateful nation will look after those who serve their country and come home wounded in body or mind. ♦

Advertisement