The Long and complex history of the Independent State provides critical context to Russia’s “Special Military Operation”

When Russia began a full-scale invasion of Ukraine in the early morning hours of Feb. 24, 2022, Western experts were puzzled about Russia’s strategy.

It seemed obvious that the roughly 200,000 Russian troops amassed along the Ukrainian border would not be sufficient to conquer and control all the country, a nation about the size of France and with a population of some 44 million.

Russian tactics during the first phase of the war also seemed unequal to the task. The plan involved landing paratroopers on an airfield near the Ukrainian capital, then attacking strategic targets in Kyiv with small groups of lightly armed, mobile infantry.

Oleg of Novgorod helped lay the foundation for the first known state centred around Kyiv.[Ivan Vdovin/Alamy Stock Photo]

This gambit seemed to assume that taking control of the Ministry of Defence and the presidential administration buildings would cause Ukrainian defences to disintegrate. The bulk of the Russian forces could then be used to extinguish the remaining “hotbeds of resistance” in central Ukraine and isolate the western provinces.

Such a campaign was clearly based on a Russian perception of Ukraine that diverged from that which was understood by Westerners and Ukrainian authorities.

Now that the original Russian war plan has failed, it is valuable to consider what Russian President Vladimir Putin and his advisers misunderstood about Ukraine.

On the morning of the invasion, Putin gave a rambling televised speech that was unlike anything heard in Europe since the Second World War. He said that Ukrainian territory was historically a part of Russia, repeating a stance he had taken in a speech three days earlier. In that address, Putin also said, “Ukraine is not just a neighbouring country. It is an inalienable part of our own history, culture and space.”

Putin’s denial of Ukraine’s legitimacy as a nation or culture is important background information for those who see his army’s alleged war crimes during the conflict as genocide. For centuries, these two arguments have been recurring themes in Russo-Ukrainian relations. The imperial narrative, which Putin has reinterpreted, obscures and rewrites the complex history of the region.

A large convoy of ground forces moves toward Kyiv days after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.[Satellite image © Maxar Technologies]

At the dawn of the Ukrainian and Russian histories, the power relations in the region of Eastern Europe that the two countries now occupy did not benefit the latter.

It was Scandinavian warriors and traders known as Rus’ (pronounced “roos”) who, in the ninth century, created the first known state in the area centred around Kyiv. Within a century, the distinction between the Norse and the local Slavs disappeared as elites of the two groups intermarried and began adopting Slavic names.

Kyiv, on the western bank of the Dnipro River that connected the Scandinavian and Mediterranean regions, prospered as the trade and administrative capital. Medieval Slavic literati called this country—then Europe’s largest—Rus’ land, and later historians referred to it as Kyivan Rus’.

In the late ninth century, Kyiv adopted Christianity from the Byzantine Empire, but the separation between Eastern and Western Christianity was not yet set in stone and the grand princes of Kyiv freely intermarried and built military alliances with other European states.

In the 12th century, the gradual migration of the Rus’ to the northeast saw the territory’s border move to where Moscow now stands, claiming the area from the local Finno-Ugric tribes. The settlement in the area was likely just a small fort with a wooden stockade.

The late, prominent Ukrainian historian Mykhailo Hrushevsky compared the relations between Kyiv and the northeastern frontier to the connections between ancient Rome and its Gaul provinces in present-day France. Modern Russian historians have struggled to reject the political and cultural superiority of medieval Kyiv. Putin, too, won’t acknowledge that the “mother of all Rus’ cities,” as the Primary Chronicle, a history of Rus’ land from about 850 to 1110, called Kyiv, is now the capital of Ukraine.

As Kyivan Rus’ expanded, the grand princes of Kyiv granted their brothers and sons new areas, which eventually grew more autonomous and established their own dynasties.

When the Mongol army arrived at the borders of Rus’ in the 13th century, the Rus’ princes’ defence was easily overcome. On Dec. 6, 1240, the Mongols broke through the Kyiv walls and laid waste to the city. Kyivites not killed were enslaved, and a fire destroyed most of city’s wooden buildings.

In Ukrainian history, the fall of Kyiv is seen as a tragedy and its date remains a meaningful reference for Ukrainians today; its anniversary is marked publicly, and commentators often compare subsequent calamities, including very recent ones, to that infamous catastrophe.

The Mongol conquest is interpreted very differently in Russian history. The princes of Moscow grew to prominence under Mongol rule. They were faithful subjects of the Mongol khans and their efficient tax collectors. The title czar, or tsar (from Latin Caesar for emperor), was originally applied to the khan before any Muscovite prince dared claim it for himself.

In the 20th century, some Russian political thinkers argued that the Russian tsars and Bolshevik commissars inherited the historical mission of the Mongol Empire, which they interpreted as controlling the vast land spaces of Eurasia stretching from Eastern Europe to the Pacific. Some scholars say Putin and his advisors are directly influenced by such Eurasianist theories.

By the 15th century, the Mongol authority was in decline and the Rus’ lands were divided between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the west and the Principality of Moscow in the east.

One hundred years later, Lithuania formed a constitutional union with Poland to create the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, with most of the Rus’ lands reassigned to its Polish part. Its residents, who called themselves Rusyns, became familiar with European political concepts, including the rights and freedoms of the ruled, which were protected by a social contract with the rulers.

Residents could study Latin at European universities. And Rusyn princes and nobles could reach the highest ranks in the Polish-Lithuanian army, as Prince Kostiantyn Ostrozky did in the 16th century. He served as the supreme military commander of Lithuania and in 1514 defeated Moscow’s 80,000-strong army in the Battle of Orsha (the 30th Mechanized Brigade of the Ukrainian army is now named after him).

The Rusyns, however, remained committed to Eastern (Orthodox) Christianity, which separated them from the Catholic Poles and Lithuanians. Ostrozky’s grandson funded the printing of the first complete Bible in Old Church Slavonic and founded a college for Orthodox Rusyns. Of course, they had this religion in common with the Muscovites, who otherwise had very different political and cultural views.

The grand princes of Moscow and, later Muscovite tsars, saw themselves as absolute rulers who “owned” their entire domain, including its subjects. Moscow also rejected Latin learning as heretical, segregated upper-class women and isolated foreigners in special residential blocks.

A painting depicts the Battle of Orsha, where Moscow troops were defeated in Rus’ land, part of present-day Belarus, in 1514.[Hans Krell/National Museum in Warsaw/Wikimedia]

It took a major social crisis in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, where the Rusyn peasants resisted the spread of serfdom to push them toward the Muscovites. By the 17th century, many Rusyn noble families in the Commonwealth—including Ostrozky’s great-grandson—converted to Catholicism and assimilated into Polish culture.

In 17th-century Ukraine, the Cossacks also came to see themselves as protectors of the Orthodox faith and Rusyn people.

Growing social and religious discontent led peasants to flee the southern steppes, where frontier guards called kozaky (Cossacks) protected Poland from Ottoman and Tatar raids. Cossacks were known throughout Europe as a

formidable, if sometimes unruly, cavalry that was credited with saving Poland from the immense invading army of Sultan Osman II during the Battle of Khotyn in 1621.

In 17th-century Ukraine, the Cossacks also came to see themselves as protectors of the Orthodox faith and Rusyn people. Their leaders, called hetmans in the Polish tradition, were statesmen as well as generals.

In 1648, with social and religious tensions rising, a Western-educated Cossack officer named Bohdan Khmelnytsky launched a massive uprising against Polish rule and proclaimed himself a hetman. Peasants joined en masse, claiming the status of the Cossacks and the personal freedoms that came with it.

A skilful military leader and diplomat, Khmelnytsky engaged in a prolonged and violent war with Poland. This eventually resulted in the king granting full autonomy to the three Ukrainian provinces constituted as the Hetmanate—a semi-military civil government divided into regiments and headed by an elected hetman.

By 1654, Khmelnytsky was forced to seek an ally in Russia. Tsar Alexis agreed to accept the Ukrainian Cossacks “under his hand,” the exact meaning of which is still disputed by historians. Regardless of the accord’s interpretation, it started the gradual process of the Russian influence in Ukrainian lands.

while another work shows frontier guards, known as Cossacks, in what is now Ukraine standing their ground to an ultimatum from the Ottoman Empire in the late 17th century [Ilya Repin/The State Russian Museum/Wikimedia]

During the reign of Catherine the Great in the late 18th century, the Russian Empire dismantled the remnants of Cossack autonomy. The country’s last empress regnant gave explicit instructions to erase any administrative and cultural differences between Russia and Cossack Ukraine, which imperial bureaucrats called “Little Russia.” Catherine forced the last hetman to retire in 1764, and the Russian army destroyed the Cossack stronghold of Zaporozhian Sich on the lower Dnipro River in 1775.

The families of many Cossack officers assimilated into the Russian nobility. Some, however, eventually began to imagine the Ukrainian nation on a new foundation—that of the peasant language and customs. Like elsewhere in Europe, ethnicity came to define modern nationalism in Ukraine, here in the form of the folk songs and embroidered shirts of peasant serfs and the memories of the Hetmanate.

Modern ethnic identity in Ukraine has another dimension, too. The Hetmanate did not include all the former Rus’ lands; Poland also retained significant territories, where ethnic Ukrainian peasants constituted a majority. And the Ukrainian Cossacks who distinguished themselves at the Battle of Vienna in 1683—the last Ottoman attempt to conquer central Europe—came from that part of Ukraine, west of the Dnipro.

While Catherine II had managed to see Russia take the largest chunk of these lands during the partitions of Poland in the late 18th century, some westernmost Ukrainian lands ended up in the Habsburg Empire. That monarchy referred to Rusyns as Ruthenians, a term derived from Latin, and allowed them much greater cultural and political freedom.

Beginning in the 1860s, Ukrainian intellectuals in the two empires established close contacts, at first based on their mutual admiration for the national bard Taras Shevchenko, a renowned poet active in the first half of the century who had been born a serf.

The notion of ethnic unity between Little Russians and Ruthenians informed the first maps made of Ukrainian ethnolinguistic territories in the 1870s. By the turn of the last century, patriotic activists in both regions began calling themselves “Ukrainians” and some embraced the idea of a united and independent Ukraine.

The First World War would give Ukrainians a chance to build their state. In the decades leading up to the conflict, the Russian Empire continued to deny that Ukrainians were a separate ethnic group—a stance recently revived by Putin. Russia also banned Ukrainian-language publications. Conversely, in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Ukrainians were recognized as one of 11 main ethnic groups and were politically active. But that was the extent of Ukrainian autonomy.

The war changed all that. The Habsburg commanders allowed the creation of a Ukrainian volunteer unit, the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen. Meanwhile, Ukrainian political activists shared lectures about the right to national self-determination with Ukrainian PoWs in German camps. And while Russia didn’t allow ethnic Ukrainian units until 1917, its earlier acceptance of Czechoslovak and Polish legions legitimized the ethnicization of the war. Both Russia and Austria also distinguished the ethnicity of the enemy, which only reinforced the concept.

Russia’s denial of Ukraine’s right to independence—or even any cultural differences from Russia—is a recurring theme.

The collapse of the Russian monarchy in March 1917 ignited mass enthusiasm for the creation of Ukrainian units. The army command had no choice but to approve them, just as the Russian Provisional Government had to accept the autonomy of the Ukrainian People’s Republic.

Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin, who acknowledged Ukrainian nationalism in the early 20th century, gives a speech in Moscow in 1920. [Wikimedia ]

In 1918, the republic was briefly replaced with a monarchy under hetman Pavlo Skoropadsky, a Russian general of distant Ukrainian lineage. But the republican forces returned in December.

The Habsburg Empire had also collapsed by then, and another Ukrainian republic sprang up in the western region of the present-day country. The two republics united in a solemn ceremony in January 1919. Independent Ukraine, however, didn’t survive beyond 1920 because the Allies refused to support it, preferring to either restore Russia or enlarge Poland. The Bolsheviks, ultimate winners of the Russian Civil War, had little choice but to create their own puppet Ukrainian republic, later part of the Soviet Union.

Then Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin acknowledged the strength of Ukrainian national feeling, as well as the new international order in which nation states were becoming the norm. Granting Ukrainians a republic within the Soviet Union was an inventive way of keeping them within the reconstructed Russian Empire. This step was unavoidable after the independent Ukrainian republic emerged in 1917, then claimed its authority over all Ukrainian ethnographic lands.

During the 1920s, in an effort to make the Soviet Union more worldly and to mobilize political support within the country, the Bolsheviks supported Ukrainian cultural development and social advancement. That period ended, however, within a decade as Soviet leader Joseph Stalin engineered a massive famine that killed some four million peasants in the early 1930s. The secret police also arrested and executed leading Ukrainian cultural figures.

During the

First World War, the Habsburg Empire allowed the creation of the Ukrainian

Sich Riflemen volunteer unit.[wikimedia]

Together, these events in 1932-33 are considered by Ukrainians as part of a genocide called the Holodomor (literally translated from Ukrainian as “murder by starvation”). The Holodomor truly ended the period of Ukrainian revolution that had begun in 1917.

By August 1939, when Stalin and Adolf Hitler signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact to divide Poland, Ukraine (then officially known as the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic) was firmly under the Soviet dictator’s control. When the Red Army stormed Poland from the east following the Nazi invasion from the west in September, Stalin claimed he was liberating large parts of eastern Poland in the name of Soviet Ukraine. While he encountered the radicalized successors of the original Ukrainian nationalists, they were ruthlessly repressed.

The Ukrainian experience of the Second World War was therefore inherently complex. Most Ukrainians were either fighting Nazism with the Red Army or supporting loved ones doing so. This meant rooting for the victory of one dictatorial regime over another.

Hitler planned to make Ukrainians slaves to German masters. They were to be denied medical care and education beyond elementary school. The Nazis starved Ukrainian cities—claiming the provisions were needed for their army and the Reich—and millions of Ukrainians were sent to Germany as slave labourers.

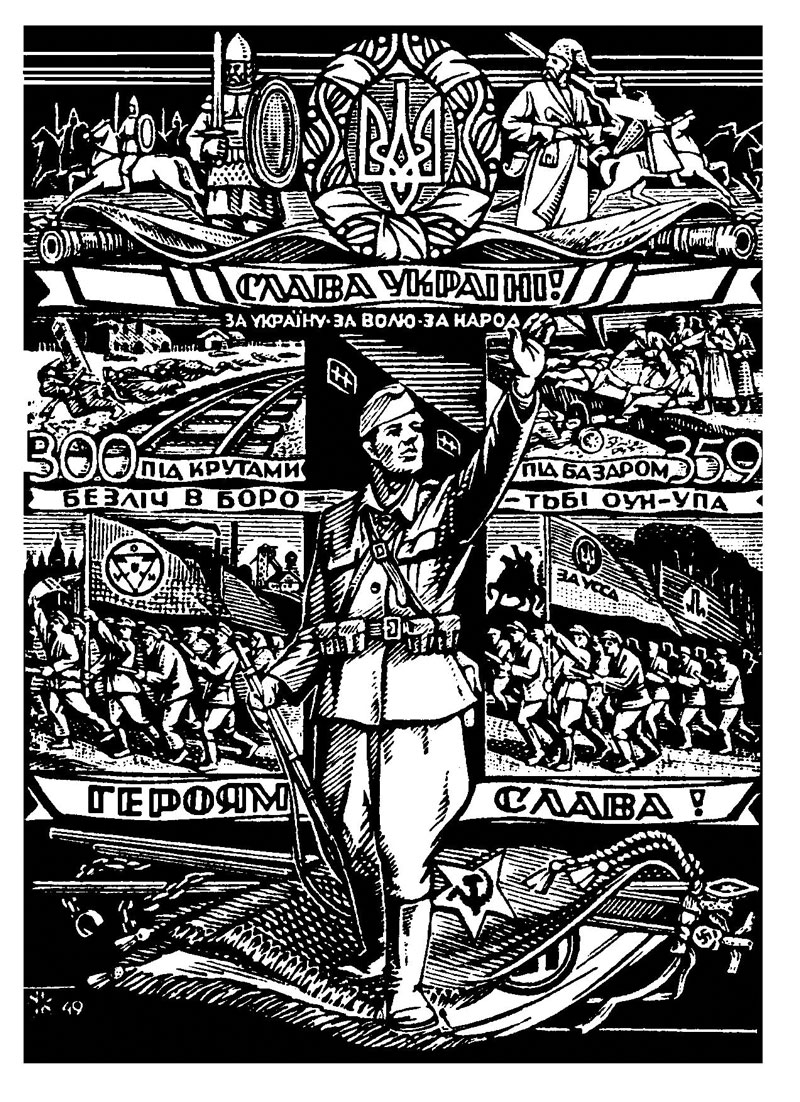

Nevertheless, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) at first hoped that Hitler’s violation of the Treaty of Versailles would benefit them. Those hopes ended on June 30, 1941, when German-led forces captured Lviv. When the OUN attempted to declare Ukrainian independence in Lviv, the first major city taken from the Soviets, the Germans arrested the leadership of the group’s largest wing, the Banderites, and began killing its supporters.

Some Banderites had been working as police in occupied Ukrainian territory and participated in the Holocaust and other Nazi war crimes, as Putin has highlighted. Likewise, the smaller wing of the OUN, the Melnykites, helped create the German 14th SS Volunteer Division “Galicia” in 1943, ostensibly for local defence from advancing Soviets. The Nazis, however, did not allow the term “Ukrainian” in the division’s name. They also never made peace with the Banderites, who formed the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) in 1943 to fight both the Nazis and the Soviets.

A propaganda poster for the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, which formed in 1943 to fight both the Nazis and the Soviets, includes the phrase “Glory to Ukraine — Glory to (her) Heroes.” [Wikimedia ]

After Ukraine regained its independence in 1991 following the fall of the Soviet Union, the country acknowledged two trends in anti-Nazi resistance: one pro-Soviet, the other nationalist. Because the Nazis had occupied all of Ukraine, modern Ukrainian school textbooks frame the Second World War as a tragedy, which included limited Ukrainian collaboration. The Holocaust is an important part in the Ukrainian story of the war, as well as in state ceremonies and memorials unveiled or under construction.

This interpretation has produced commemorative practices increasingly at odds with Soviet-style celebrations of the state’s military might. In 2015, Ukraine established May 8 as the Day of Remembrance and Reconciliation; it also adopted the Western remembrance symbol of the poppy and the motto, “Never again.”

In contrast, Putin’s Russia has continued the Soviet tradition of the “Great Patriotic War” with massive parades on May 9 (Victory Day, Moscow-time). The story of widespread Russian collaboration with the Nazis and the Soviet Union’s alliance with Nazi Germany between 1939 and 1941 is suppressed. Russian historians and diplomats dismiss the Red Army’s war crimes, such as the mass rape of German women, as “fake news.”

The role of the Western Allies during the time is minimized in Russian school books, and Stalin is still given credit for the victory, which explains the consistently high opinion of him in Russian polls. This narrative of the war serves to legitimize Putin as a new dictator who is not only employing Stalinist methods but, ironically, also repeating some of Hitler’s miscalculations.

Just as Hitler believed that the Soviet Union was a weak state run by “Judeo-Bolsheviks” that would collapse the moment his armies attacked, Putin, it appears, believed Ukraine was run by Nazi nationalists whose authority would disintegrate the moment Russian helicopters dropped a small landing party of paratroopers in Kyiv. Of course, neither the Jewish identity of Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, nor the stance of his Servant of the People political party, fit the description.

Putin seems to have modelled his “special military operation” in Ukraine on the Anschluss, the 1938 annexation of Austria by Germany. On March 12, the Germans invaded. The following day, a Nazi government was established, and Hitler proclaimed the union of the two countries.

Today, however, the 1930’s rules of ethnic politics no long apply. Modern nations, rather, are multiethnic, political communities held together by shared ideas rather than blood and race. So, when a quick victory failed to materialize, Putin’s forces applied more firepower and pushed the legal limits of war to their extremes—at least one Russian pleaded guilty to war crimes and numerous other unlawful incidents are under investigation. Some Western leaders have labelled some of Russia’s actions genocide.

Citizens flee the city of Irpin, northwest of Kyiv, in March 2022 following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. [Dimitar Dilkoff/AFP via Getty Images]

Russian attitudes toward Ukraine are not only grounded in the distant past and fuelled by imperial nostalgia—they have also been shaped by relatively recent events. After the Second World War, the Soviet Union faced a staunch insurgency from Ukrainian nationalists in western regions that continued until the early 1950s. That era gave rise to Soviet propaganda framed around the idea of Nazi Ukrainians—not just UPA fighters, but any patriotic Ukrainian. Putin has revived this notion.

Ironically, one of the reasons the Soviets transferred the Crimean Peninsula to Ukraine in 1954 was to make the country more Russian. However, historically, the Crimea is neither Ukrainian nor Russian. It was the homeland of the Crimean Tatars, whom Stalin had deported in 1944. It was postwar settlers moving into deserted Tatar homes that made the Crimea “Russian.”

Likewise, the ethnographic model of national identity that developed in Ukraine after the Second World War reinforced Russian cultural attitudes of superiority. Then, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the state-abetted cultural assimilation in Ukraine led outsiders to assume that all Ukrainians spoke Russian, with Ukrainian heard only in villages and in “nationalistic” western regions. Ukrainian identity was characterized by dancing and folk songs, rather than by its democratic institutions and multi-party political system.

The difficult post-Cold War economic transition fuelled nationalist resentment in Russia and among Russians in the Crimea. The loss of each Soviet republic was a blow to Russia’s imperial pride, but Ukraine’s departure hit hardest because it challenged both Russia’s historical greatness and its undeveloped sense of ethnic identity which, for many, included Ukrainians. The bitterness was directed at Ukraine.

As Russia crept toward authoritarianism, Ukraine was viewed as politically chaotic.

While Russia’s economy flourished in the new century thanks largely to its mineral wealth, having no similar resources Ukraine’s continued apace. And as Russia crept toward authoritarianism, Ukraine was viewed as politically chaotic—though it really was democratic. This is, perhaps, the most underappreciated reason behind the Russian invasion.

Russian economic prosperity coincided with the tightening of political controls and the rise of Putin, whereas Ukraine has remained a democratic state where presidents have changed regularly. Ukraine also has a robust civil society, which twice in the 21st century has rebelled against attempts to impose Russian-style authoritarian rule—during the Orange Revolution (2004-05) and the Revolution of Dignity (2014). Between these two events, Russian authorities also focussed on suppressing 2011-12 protests within Russia against Putin’s continued rule. Putin claimed the protests within Russia were Western-sponsored and inspired by the Ukrainian example.

Following the 2014 revolution, which saw the ousting of President Vikor Yanukovych, who had pursued closer ties with Russia, Russia annexed the Crimea and sponsored the war in Ukraine’s Donbas region near the Russian border. The aim was to punish Ukraine and teach Ukrainians a lesson. Russian-backed separatist rebellions in other eastern Ukrainian regions didn’t work, thus depriving Russia of a land bridge to the Crimea. Russian troops performed reasonably well, however, against the underfunded Ukrainian army in the Donbas. To Putin, this confirmed the inferiority of Ukrainian identity.

But the setbacks Russia has encountered during this year’s invasion—tens of thousands of troops lost, more than a dozen generals dead, its flagship Black Sea warship sunk—revelaed Putin’s error. A notion of Ukraine as a democratic, political community is animating this struggle. Putin dismissed the power of democracy at his peril.

Advertisement