Kherson residents celebrate during a visit by President Volodymyr Zelesnkyy following the Russians’ withdrawal from the city.[Wikipedia]

Rooted out of a café at the centre of the city, partisans gathered grassroots intelligence from rooftops, roadsides, security cameras and farm fields, the latter where they pretended to tend livestock while recording the movements of Russian formations.

In one case, the citizen spies provided photographs and coordinates of an electronics store-turned-Russian field hospital, barracks and storehouse—with enough detail and precision that Ukrainian forces were able to destroy the site.

The café was an intelligence hub. Its 30-something owner Vova, who recently spoke to The Economist on the condition of anonymity, kept his business going throughout the occupation, recruiting and organizing spotters, gathering information and serving as a conduit to the Ukrainian military.

As the information came in, Vova would pass it along to a friend, Denys, with whom he had played paintball and was now fighting the unprovoked invasion launched by Russian President Vladimir Putin on Feb. 24, 2022.

Vova imparted Russian military positions, strength, movements and more.

Officials say thousands of everyday citizens throughout the country are sending pictures and information to the Ukrainian military.

Russians took over the courthouse across the street from the café, and Russian security (FSB) officers billeted themselves in nearby hotels. Wearing black baseball caps and pistols holstered to their bodies, and with SUVs with tinted windows parked in front, they would gather at a restaurant around the corner.

Vova served takeout coffee and shot iPhone video, sometimes through the front curtains of his café. He even mounted his phone on his vehicle’s dashboard and drove around recording video of the homes and hotels housing Russian officials.

With the onset of warmer weather, a retired woman living in a ground-floor flat nearby opened her window and began eavesdropping on conversations between Russian soldiers camped outside.

She took to acting the role of motherly babushka, asking for names, hometowns, news, then she would walk her dog to Vova’s café and relay what she had heard.

Vova made his invaluable reports to Denys daily.

“Throughout the occupation, his voice was like hope for me,” Vova told the newspaper. “He was my connection to the outside world. But I never asked where he was. I knew it was better if I didn’t know.”

Officials say thousands of everyday citizens spread throughout the country are sending pictures and information to the Ukrainian military.

Oleksiy Danilov, head of Ukraine national security, told The Wall Street Journal in December that partisans such as Kherson’s will help the country’s continuing campaign to recapture Russian-occupied territories.

“It’ll be the same in Donetsk, in Luhansk, and everywhere,” he said. “Our guys and girls are everywhere.”

“Restaurants and cafés are in many ways the lifeblood of espionage.”

Protracted military invasions and, particularly occupations, are fraught with risks they will be compromised, even overthrown, not by military might or professional intelligence operatives, but by unarmed, unequipped and untrained citizen spies with little more than two working ears and/or at least one functioning eye.

Beyond the partisan fighters made famous by the French and Dutch Resistance forces of the Second World War, these everyday folks often work in plain sight of, even side-by-side with, the enemy—listening, observing, reporting.

They gather intelligence in places as diverse as farm fields and crowded city intersections. Pubs, cafés and eateries are preferred intelligence-gathering locations.

“Restaurants and cafés are in many ways the lifeblood of espionage,” says former spy Amaryllis Fox, whose 2019 memoir Life Undercover: Coming of Age in the CIA, recounts her post-9/11 adventures infiltrating terrorist networks in 16 countries.

“Restaurants offer the opportunity to meet the people we most seek,” she continues. “Sometimes those meetings are accidental. Mostly, they are planned to look accidental.”

Most often for citizen spies, there is no meeting. It’s passive intelligence-gathering.

During the War of 1812, Laura Secord is famously said to have overheard the chatter of U.S. troops billeted in her commandeered home in occupied territory on the Niagara Peninsula. The Americans spoke over dinner of a planned attack.

The wife of a wounded Loyalist soldier, she stole away in the early-morning hours of June 22, 1813, and walked 32 kilometres from present-day Queenston, Ont., through St. Davids, Homer, Shipman’s Corners and Short Hills at the Niagara Escarpment before she arrived in the camp of allied Mohawk warriors.

The Indigenous fighters guided her to the British lines, where she told Lieutenant James FitzGibbon what she had heard. The British/Mohawk force repelled the American attack two days later at the Battle of Beaver Dams.

No mention of Secord specifically was made in official reports following the battle—possibly to protect her—and her contribution was all but forgotten until 1860, when a visiting Edward, Prince of Wales, awarded the impoverished widow 100 pounds (almost C$22,000 today) for her service. She died in 1868 at 93.

Laura Secord has since become a household name in Canada. She is the celebrated subject of books, plays and poetry; her moniker given to schools, monuments and a museum; her face on a memorial, a stamp and a coin. One of the country’s most popular brands of chocolate bears her name and, ostensibly, her silhouette.

“There are not that many examples of women who actually shot collaborators themselves.”

As a teenager in occupied Holland during the Second World War, Freddie Oversteegen used her feminine wiles to attract Nazi officers, then killed them.[Wikipedia]

She was just 14 when she and older sister Truus started handing out anti-Nazi pamphlets around their occupied city of Haarlem, Netherlands.

Their activities were quickly elevated in 1941 after they were recruited by the area Resistance commander, with their activist mother’s permission, and their tools went well beyond their eyes and ears.

Oversteegen and Truus worked to sabotage the Nazi occupation, dynamiting bridges and railroad tracks and helping to smuggle Jewish children out of the country and escape concentration camps.

They also killed German soldiers and Dutch collaborators, executing drive-by shootings from the backs of their bicycles or luring enemies to the woods under the pretense of a romantic overture, then killing them.

Oversteegen even approached soldiers in taverns and bars and asked them to “go for a stroll” in the forest, where a Resistance executioner awaited them. SS officers were prime targets.

Eventually, the duo focused on Dutch collaborators who arrested or compromised Jewish refugees and Resistance members.

“They were unusual, these girls,” Bas von Benda-Beckmann, a former researcher at the Netherlands’ Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, told History Television in 2018. “There were a lot of women involved in the resistance in the Netherlands but not so much in the way these girls were.

“There are not that many examples of women who actually shot collaborators themselves.”

Jannetje Johanna (Hannie) Schaft was caught and executed by the Nazis just three weeks before the war ended. [Wikipedia]

The Nazis arrested and killed Schaft in 1945, just three weeks before the war ended in Europe. “I’m a better shot,” she uttered to her executioner after he initially only wounded her. They were her last words.

The work and its consequences took its toll on the sisters. Truus became a sculptor and wrote a book about her wartime experiences; Freddie, who fought the urge to help those she had shot, battled insomnia and coped “by getting married and having babies.”

“We did not feel it suited us,” Truss told anthropologist Ellis Jonker for his book Under Fire: Women and World War II. “It never suits anybody, unless they are real criminals.”

Both sisters died at age 92—Truus in 2016; Freddie in 2018.

No one was safe. Husbands and wives informed on each other, and relatives and friends snitched when someone stayed at another residence.

East Germany’s Stasi, or ministry for state security, elevated the concept of citizen spies during the Cold War, by recruiting hundreds of thousands of informants, or inoffizielle Mitarbeiter, between 1950—a year after the Germanys were partitioned—and the start of reunification with West Germany in 1989.

Their role: to spy and report on the doings of their fellow citizens. The Soviet Union, under Josef Stalin, employed citizen spies and informants, but it was arguably the Stasi that gained the most notoriety for its methods.

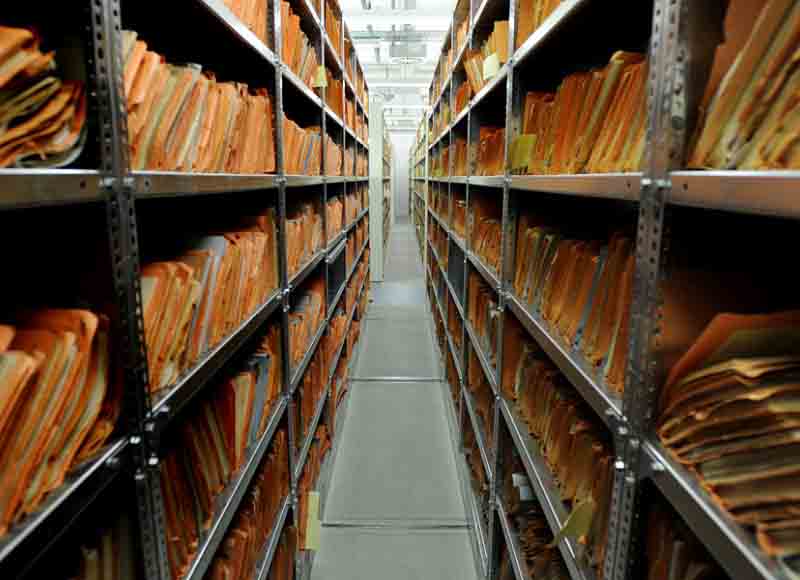

Surviving Stasi files are housed in a massive archive. After the collapse of the east bloc, personal files could be viewed on request.[The Cuban Economy]

Based on the volume of material destroyed in the Communist regime’s last days, the office of the Federal Commissioner for the Stasi Records has said there could have been as many as 500,000 informers. A former Stasi colonel estimated that the figure could be as high as two million, counting occasional informants.

With its headquarters in East Berlin, the Stasi’s network of civilian informants formed the foundation of its domestic operations. The citizen spies were responsible for the bulk of the 250,000 arrests the Stasi made.

The agency was ubiquitous, present in virtually every aspect of East German life. Full-time officers were posted to major industrial plants and one tenant in every apartment building was a designated watchdog, reporting to an area representative.

No one was safe. Husbands and wives informed on each other, and relatives and friends snitched when someone stayed at another residence. Tiny holes were drilled in apartment and hotel room walls through which Stasi agents filmed citizens.

The ministry infiltrated schools, universities, clubs and hospitals.By the time the regime collapsed in 1989, about one in 63 East Germans were collaborators.

Informants were made to feel important. They were given material or social incentives and a sense of adventure. Only 7.7 per cent, according to official figures, were coerced into co-operating. Blackmail, however, was not uncommon.

Many informants were tram conductors, janitors, doctors, nurses and teachers—people in frequent contact with the public.

Stasi ranks swelled after East Bloc countries signed the 1975 Helsinki accords. East German leader Erich Honecker considered the binding clause to respect “human and basic rights, including freedom of thought, conscience, religion, and conviction” a grave threat to his regime.

The number of citizen spies peaked at around 180,000 in 1975 after slowly rising from 20,000 to 30,000 in the early-1950s and reaching 100,000 for the first time in 1968.

By the time the regime collapsed in 1989, about one in 63 East Germans were collaborators. By some estimates, the Stasi maintained greater surveillance over its own people than any secret police force in history.

The Stasi employed one secret officer for every 166 East Germans, compared to the Nazi-era Gestapo, which deployed one per 2,000. Counting part-time informers, the Stasi had one agent for every 6.5 people.

Numerous Stasi officials were prosecuted after the reunification and its surveillance files on millions of East Germans were declassified so that anyone could inspect their personal files on request.

Today, particularly since 9/11, the Canadian Security and Intelligence Service employs everyday people to monitor their fellow citizens, especially in communities the spy service deems vulnerable to outside influence.

“We would hear them talking about collecting hands and feet from the wreckage.”

The Russians in Kherson started infiltrating what had become known as the Telegram Network, after the encrypted messaging app the citizen spies preferred. The infiltrators began spreading disinformation.

“We would get reports that there were 1,500 troops and 200 tanks in a certain village,” a Ukrainian officer told The Economist. “But then we would check with our people in a neighbouring village and they hadn’t seen anything.”

Over the summer, people Vova knew started disappearing—classmates, friends, paintball teammates. But Vova, who did not hide and was often seen with his newborn son, went untouched.

At the end of June, Ukrainian forces had acquired American-made high-mobility artillery rocket systems, or HIMARS. With a range of 80 kilometres, their impact was immediate.

The new rockets took out barracks, headquarters and tank emplacements. They punched holes in an important bridge, denying the occupiers a key supply route.

Russian troops were soon demoralized.

“We heard their conversations in which they would say ‘the Ukrainians have this new superweapon; we can’t hide from it,’” the officer said. “We would hear them talking about collecting hands and feet from the wreckage.”

One day in September, Vova’s military contact, Denys, told him he should close the café for a day. Vova suspected a rocket attack on the court building opposite was imminent. But he feared closing his business would draw suspicion.

Around 1 p.m., he saw people pouring out of the building, jumping into cars and racing away. It appeared the Russians had been tipped off.

No rocket strike came. The Ukrainian military changed gears, held off and bided its time.

On Sept. 16, 2022, Vova was in the square, his son asleep in his stroller. The barista noticed a significant number of important-looking people gathering at the courthouse. Vova informed Denys immediately, then took his son to a nearby park.

Less than a half-hour later, he heard and felt the HIMARS strike. He called his wife to come pick up their son, then made his way back.

“Ambulance sirens screamed,” The Economist reported. “Soldiers barked ‘Everyone leave!’ Neighbours later told Vova they saw corpses being brought out of the building all night.”

The café suffered only a few broken light bulbs.

On Nov. 9, the retreating Russian army announced it was pulling out of Kherson. The first Ukrainian troops entered the city two days later.

Then one day, Denys appeared at the café door.

“He weighs 100kg and he was wearing armour,” Vova told the newspaper, “but I picked him straight up in the air and hugged him.”

Advertisement