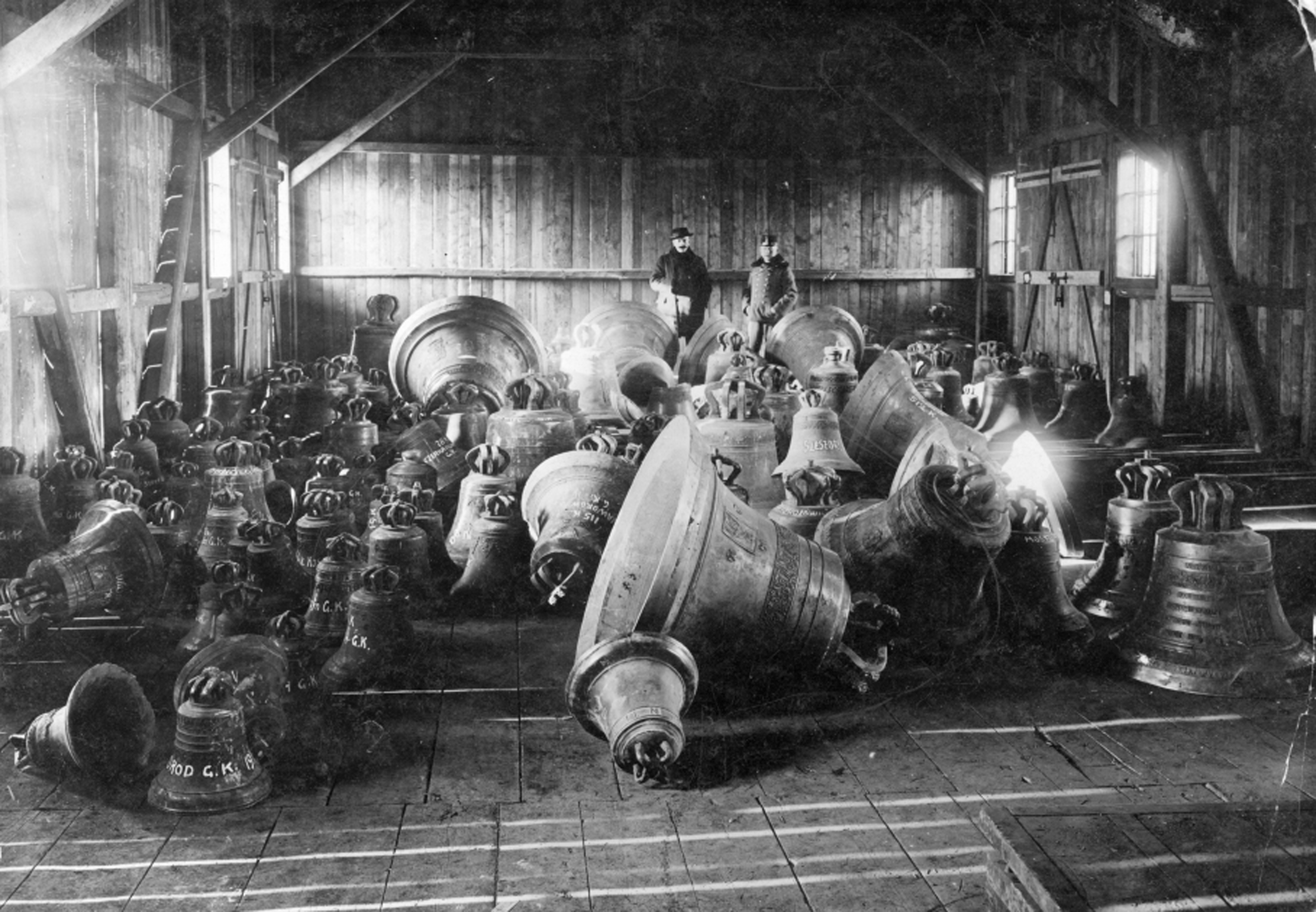

Bell cemetery in Hamburg after the Second World War. [Bundesarchive]

In Germany and across Europe, tens of thousands of bronze bells—some imparting “the songs of the angels” since the 12th century—had been seized and melted down for arms and munitions.

During the First World War, 44 per cent of the bells in Germany alone were lost, many given willingly to support the war effort—and some not so willingly.

In the parish of Kusel in southwestern Germany, Deacon Karl Munzinger had grudgingly resigned himself to the inevitable after resisting a decree ordering the surrender of bells to be melted down and converted to guns and shells.

Six bells of the Vienna Church of St. Leopold on the way to the arsenal for melting down into armaments on Sept. 12, 1916. [Wiener Stadt- und Landesarchiv]

The practice wasn’t limited to the conflict of 1914-18, either.

First World War German gas alarm bell captured in 1918 from the German trenches at Gavrelle near Vimy Ridge in France. [IWM/FEQ848]

Benito Mussolini’s government actually forged a prewar agreement with the Vatican providing for the “mobilization” of Italian bells under which half were to be claimed for war industries. As was the case in Germany, at least one bell designated by local authorities was to remain in every tower.

The bells were to be broken up in Italy and the scrap sent to Hamburg for processing because Italian smelting plants did not have the capacity to meet the deluge.

Bell metal is typically made of a hard alloy usually composed of four parts copper to one part tin. It is known for its hardness and rigidity, but the Germans broke up the bells, then smelted and refined the bell metal, separating the copper, tin and other metals, including lead, zinc, even silver and gold. A tonne of bell metal would typically yield 760 kilograms of copper and 180 of the more sought-after tin.

After the Second World War, Canadian Percival Price, Canada’s first dominion carillonneur and, in fact, the designer of the Peace Tower carillon in Ottawa, was dispatched to help investigate and repatriate as many bells as possible.

Price was serving as a consultant to the Vatican Commission for the Restoration of Bells and the Inter-Allied Commission on the Wartime Preservation of Artistic and Historic Monuments in War Areas, better known as the Monuments Men.

A member of the Canadian army’s Enemy Science and Technology Investigation Section, Price spent two years helping Austrian, Belgian, Dutch, West German and Italian government commissions locate and repatriate bells.

German and Austrian troops remove bells from a church in occupied Romania in August 1917. [IWM]

The current dominion carillonneur, Andrea McCrady, said Price spearheaded a study of the tonal qualities of Europe’s bells. In his 150-page report, Price said he capitalized on the unique opportunity to draw from 12,000 surviving at the Hamburg bell cemetery.

“A lot of these bells dated back hundreds of years,” McCrady said in an interview. The process of replacing lost bells “allowed them to really analyze what bell is well-tuned and what sounds like a broken flower pot.

“After the Second World War, the Dutch and Belgian companies—the bell founders—learned so much that as they were casting new carillons they produced very well-tuned bells. So a modern carillon has a different voice entirely.”

Bells at a Hamburg Glockenfriedhof in 1942. [German National Museum, Nuremburg]

In Buddhist tradition, the bell can represent the heavenly enlightened voice of the Buddha imparting his teachings. For Buddhists, it is also a call for protection and to ward off evil spirits.

Rather than being summoned, Hindus ring the temple bell to inform the deity of their arrival. The bell’s sound is considered auspicious, welcoming divinity and dispelling evil.

After Good Friday services marking the crucifixion and death of Jesus, Christian church bells that traditionally call parishioners to worship typically remain silent until Easter morning, when they declare his resurrection.

“The silence of the bells makes clear that something has fallen apart,” Rev. Rüdiger Penczek, a Protestant pastor based near Cologne, recently told the German broadcast service, Deutsche Welle.

Falling apart, indeed.

The practice of confiscating and transforming church bells into tools of war is not new. It was a longstanding tradition of European warfare that artillery commanders had rights over the bells of conquered villages, towns and cities.

Napoleon, in particular, relished claiming this right, and added to his war coffers by requiring vanquished cities to buy back their bells. If they could not, the commanding general was entitled to dispose of them as he saw fit. Half the revenue would be his, the other half went to the central treasury. The practice was called “Rachat des cloches,” or “redemption of the bells.”

A Second World War Victory Bell made from a German aircraft shot down over Britain.

In the 18th century, bells routinely fed military campaigns. During the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71), the bishop of Nancy authorized every parish in his diocese to take down all but one of their bells to make cannons for the defence of France.

The Hague Conventions of 1910 declared church bells protected and untouchable for war purposes—to no avail.

Fearing the German advance in 1915, Russia removed 300 bells from its own churches, secreting them away at Nikolsy Monastery just outside Moscow to prevent their destruction.

Across Great Britain, regulations introduced under the sweeping Defence of the Realm Act of 1914 limited wartime bell-ringing, relegating them to the role of warning devices. That quieted about 5,000 bell towers across the British Isles. The silence, as they say, was deafening.

Beyond their role in feeding production, bell towers across Europe made ideal sniper nests and observation platforms during both wars—rendering them, in turn, prime targets for artillery, tanks and other destructive forces.

Seizing bells from St. Philip’s and James Church in Velesin, Czechoslovakia, on March 31, 1942.

The carillon, which is by definition made up of at least 23 bells, is the national instrument of both the Netherlands and Belgium. Together, the two countries have more than half the world’s 600 carillons, upwards of 200 of them in Holland alone.

The destruction of Belgian carillons, particularly, during the First World War resonated across the world and was depicted by allies as the brutal annihilation of a unique democratic music instrument created by a courageous people.

Both countries’ legacies were ravaged in the Second World War: The Nazis took two-thirds of Belgium’s bells; British investigators claimed every single bell was taken out of the Netherlands, with only 300 surviving the war in Hamburg.

To add insult to injury, in the early 1940s German occupation authorities had small bells cast in the Netherlands to commemorate their confiscation of European church bells. Bearing the inscription “the bells too are fighting for a new Europe,” they were given as mementos to leading Nazis who played key roles in implementing the seizures.

The only countries in occupied Europe spared confiscation of their church bells were Norway, Denmark, Luxemburg and most of France, where the collaborationist Vichy government struck a deal with the devil, so to speak, by claiming desecration of French cultural heritage and offering up the country’s bronze statues instead.

Bells taken by the Austro-Hungarian army in a storehouse near Lviv, Ukraine, in 1916.

In reality, Marshal Philippe Pétain wanted to ingratiate his traitorous regime with the Roman Catholic Church.

The deal, known as The Vichy Exception, failed, however, to save every Vichy French bell. Many were destroyed in attacks and bombing raids. Price reported that Rouen Cathedral lost its five swinging bells, as well as “Jeanne d’Arc,” at 20 tonnes, the largest bell in France. He said it was reduced to a pile of light ash.

Across Europe, church bells that survived First World War fighting and theft were often used to warn troops of gas attacks—an application, one could imagine, that would forever colour the sound of church bells for veterans of every stripe.

Some fallen or plundered church bells were actually taken out to the trenches themselves, where they proved more effective warning systems than the usual improvised gongs such as frying pans suspended from rope.

Bells were also powerful symbols in the all-important bond drives and propaganda campaigns of both world wars. Upon joining the allied effort in 1917, the United States used the Liberty Bell on propaganda posters and leaflets as a symbol of American freedom and a promoter of Liberty Loans.

First World War Germany also used images of bells to rally support for its war loans.

A German soldier weighs a seized church bell on the eastern front circa 1915. The tally: 567 kg.

Bells were used in early-WW I propaganda to decry “the rape of Belgium.” Reports that the monks of Antwerp had refused to ring church bells to celebrate the German victory were embellished. By the time the story was reported in Le Matin in Paris, it told of defiant monks hung up and used as human clappers.

When the shooting finally stopped at 11 a.m. on Nov. 11, 1918, and news of the Armistice broke, bell-ringers across Britain, Canada and the world spontaneously began to sound their chimes. Where church bells had been lost, clergy and parishioners waved hand bells.

And not particularly well in some places: 1,400 bell-ringers from Britain alone were killed in the war and, with so many more serving at the front, it was reported at the time that communities prevailed upon older ringers, former ringers and virtually anyone who could lend a hand to join in. As part of 2018’s ceremonies, Britain recruited and taught almost 2,800 volunteer bell-ringers to perform on Remembrance Day as symbolic replacements for those who were lost.

Dominion Carillonneur Andrea McCrady at the keyboard in the bell tower of the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa. [Stephen J. Thorne]

“To me, Remembrance Day is the most important time that I play in the entire year,” said McCrady. “After all, the Peace Tower is the Peace Tower, and it and its carillon are dedicated to peace and the memory of those who served Canada and lost their lives. It is very humbling [to play on Nov. 11]—and pretty scary, too.”

Before the National War Memorial was dedicated in 1939, the annual remembrance ceremony was conducted on the Peace Tower steps.

At the dedication of the structure on Canada’s 60th birthday—July 1, 1927—Prime Minister Mackenzie King called the carillon “the crowning feature of the memorial tower and…the most fitting symbol of the peace…the voice of a nation given in thanksgiving and praise which will sound over land and sea to the uttermost parts of the earth.”

The notes of the carillon’s 53 bells, from the 10-tonne bourdon to its 4.5-kilogram littlest brother, went out on CBC airwaves in the country’s first coast-to-coast broadcast, carrying “a message of peace and goodwill to all men in all lands.”

The bells had been cast as a rare set in 1926-27 by Gillett and Johnston of Croydon, England. The foundry, near London, was bombed out of existence during the Second World War.

Advertisement