In 1913, the militia was called out during a coal miners’ strike on Vancouver Island. Called the Great Strike of 1912-14, it was to be and remains the longest deployment of the militia in aid of the civil power in Canadian history.

The immediate cause of this strike in Nanaimo, 110 kilometres north of Victoria, was mine safety, union recognition and the firing of a union organizer. However, attempts to resolve the issues failed. After a raucous meeting at Cumberland Hall on Sept. 15, 1912, the miners voted to strike. Canadian Collieries, the owner of the Dunsmuir mine, responded by evicting the strikers’ families from company housing, hiring “scab” labour and refusing to negotiate. The unrest spread to other mines with similar results.

Over several months the confrontations grew stronger. Appeals to the acting premier and attorney general, John Bowser, for extra police saw the recruitment of 100 special constables. But the specials soon realized that the $2.50-a-day wage wasn’t worth facing an angry miner brandishing a two-by-four.

Reports of riots at Nanaimo and Ladysmith, gunfire at Extension, the number of specials leaving, finally pushed Bowser and his Executive Council to call out the militia in aid of the civil power. Scrambling to get the troops into the field, Bowser played fast and loose with the legal requirements. Two government representatives, neither a justice of the peace as required by the Militia Act, were pressed to sign the necessary requisition.

Protection: Troops march replacement workers to the mines during the strike in 1913. [Cumberland Museum and Archives, 1913/C160-005]

Colonel John Hall, who would command the gathering force, was eager to get into the field but angry about the legal machinations. “I understand that except as an honorary colonel, no member of the executive [had ever] worn the uniform of the militia.…So little had the executive thought that the militia could be effective, they had not taken the trouble to inform themselves what legal formalities were involved,” he wrote.

Hall had mobilized British Columbia’s 5th Regiment, Canadian Garrison Artillery, under Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur Currie—who would go on to lead the Canadian Corps in the First World War—along with his own regiment, the 88th Victoria Fusiliers and 50 members of C Battery of the Royal Canadian Artillery of the permanent force.

The fusiliers mustered with two machine guns and 24,000 rounds of ammunition. The troops paraded at 09:00 on Aug. 13, 1913, receiving 20 rounds of ammunition, rations for 24 hours and not much else.

At 10:00, 1913, Hall was told by Lt.-Col. Alexander Roy, the district officer commanding (DOC) of the permanent force, to proceed to the strike zone. It was an imposing force: over 1,000 all ranks that was to enforce law and order in the strike zone.

“I require you to walk out in single file

to the courthouse and anyone attempting

to run away will be bayoneted or shot!”

Hall had made arrangements privately with the Nanaimo and Esquimalt Railway for a train prepared to move at a moment’s notice. He then arranged to have the news become public. It was a time-honoured form of military deception, using a semblance of secrecy to make the tactics appear genuine.

In the meantime he had secretly arranged with Captain James Troup, supervisor of the Canadian Pacific Railway’s British Columbia Steamship Service, for the transport of the troops on the Vancouver boat leaving late that evening. When the order to leave was given, the provincial police cut the telegraph and telephone lines to Nanaimo. At 02:00, Aug. 14, the troops left Victoria, arriving three hours later at Brechin Mine where they landed without opposition.

Surprise—that rule of war—had been achieved and the rumoured 1,500 armed strikers ready to block the road to Extension never materialized. According to Hall, “All the wild stories of shooting and loss of life are without a shadow of truth. There has been a little rough work and perhaps a little horseplay, but there has been no danger to life.”

Welcomed by Nanaimo Mayor John Shaw, the troops marched into the town where, at bayonet point, a meal was obtained for them at the hotels. A detachment found no opposition at Extension, although some mine property was damaged. The families of non-striking miners had fled into the woods to escape retaliation. The troops carried out a rescue operation to collect and succour these unfortunates. Having done that, the troops marched back to Nanaimo to quell a disturbance. There was none.

When he found the phones being tapped,

he had two Seaforth Highlanders transmit

the messages in Gaelic

The troops had been on continuous duty for 24 hours, and had met no resistance. They were hungry, tired and grimy. Once again a meal was obtained at the end of a bayonet. The troops bedded down in railway cars without blankets. So far, the only demonstration of force was not against recalcitrant strikers but unwilling inn keepers who did not want to feed the troops.

As Hall’s detachments were marching, other militia units in Victoria and Vancouver were being mobilized for duty, arriving at Union Bay on Aug. 15. The Seaforth Highlanders, 6th British Columbia Regiment (Duke of Connaught’s Own), 19 Company of the Canadian Army Service Corps and the 6th Field Company of the Canadian Engineers provided another 500 men to what was now called the Civil Aid Force.

Like the units before them, they had little equipment. Still it was an imposing force, nearly 1,000 all ranks. The years of neglect of the militia by Ottawa meant the “support tail” of the Civil Aid Force was non-existent. They lacked everything from maps to field kitchens. This led a prominent Canadian militia officer, Col. William Hamilton Merritt III, to reflect that “the militia is perhaps the most expensive and inefficient military system of any civilized country.”

Still, in true military fashion, the force struggled on. A permanent camp, finally replete with tents, was established at Starks Crossing, five and a half kilometres out of Nanaimo.

Hall marched the militia from area to area, guarding mine property, to “show the flag.” For the troops, it was tedious with little indication that law and order had broken down.

Hall, finding that the telegraph operators supported the strikers, seized the telegraph office. When he found the phones being tapped, he had two Seaforth Highlanders transmit the messages in Gaelic. But there were serious legal issues. Hall’s orders were verbal—not the required requisition— conveyed by the DOC, Roy, from Bowser. Hall realized the dilemma but found that the situation at Nanaimo, as he put it, “required immediate response on my part and the acceptance of the risks of illegal action.”

Based on intelligence reports that representatives from the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), which was providing strike pay, were to arrive at Nanaimo to meet with the strikers and the discovery of a case of 24,000 rounds of ammunition by the artillery and engineers, Hall determined to launch a major operation against the union on Aug. 19-20.

After careful preparation the troops formed up as if they were to attend a church parade. Once the steamer arrived from Vancouver, the British Columbia Provincial Police, backed by the militia, arrested the men as they came off the ship. None offered any resistance. According to Hall this was “the first instance of the restoration of civil control in the strike area.”

Further operations, planned in great secrecy, were carried throughout the strike zone. At Nanaimo, while the striking miners were meeting at the Athletic Club, troops surrounded the building. Cars were driven up and their lights focused to blind anyone leaving the meeting. When the first man appeared, “it [was] impossible to describe the look of blank amazement,” Hall wrote.

The man was ordered to fetch the chairman. When the chairman came out Hall commanded, “I require you to walk out in single file to the courthouse and anyone attempting to run away will be bayoneted or shot!”

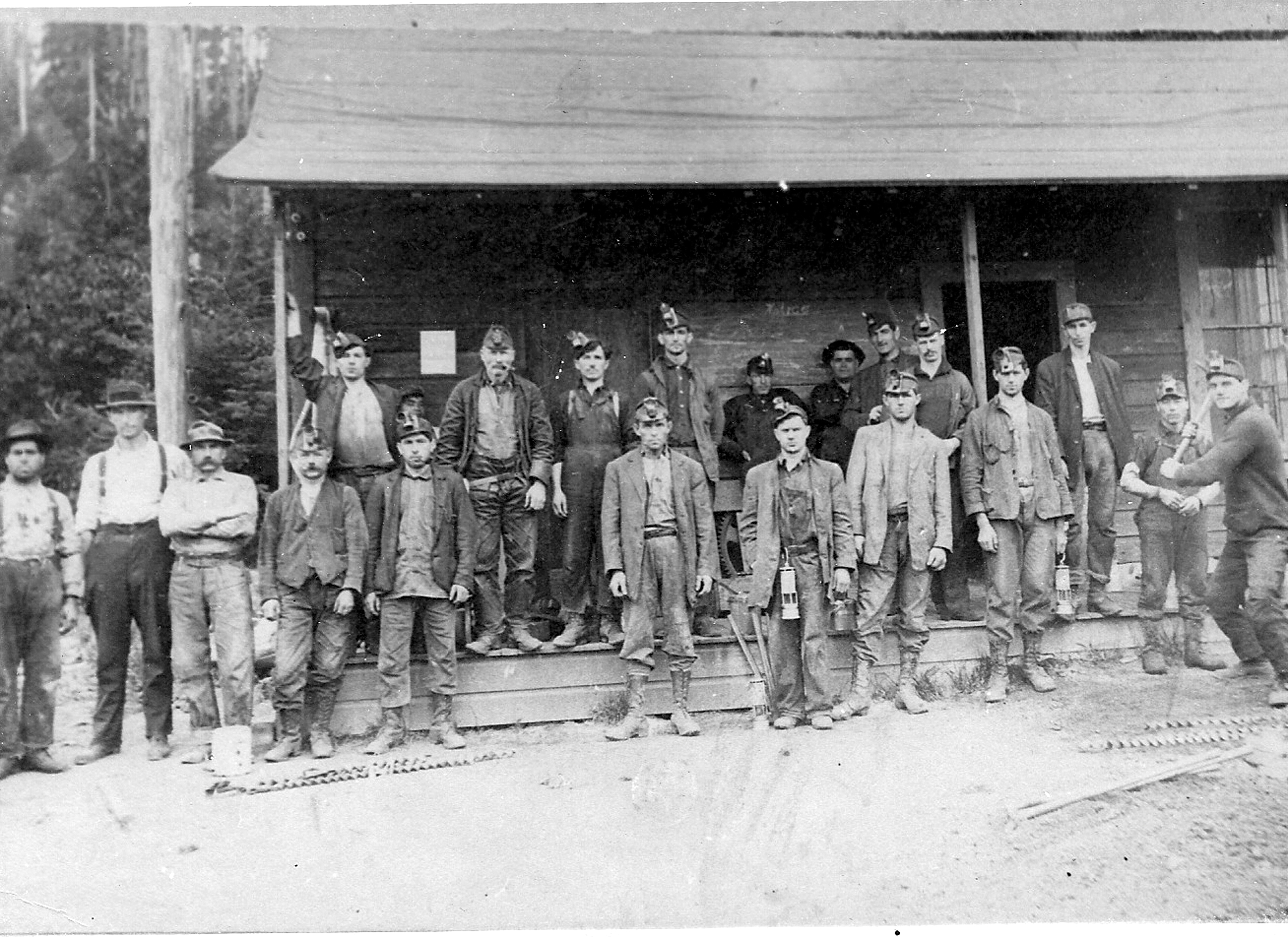

The workers: Coal miners wait to start work at an extension mine operated by Canadian Collieries in 1912. [Ladysmith Historical Society Archives]

At 01:00, the men inside the hall were allowed out. In groups of 10 they emerged into the glare of headlights. According to Hall, “The little walk in small parties for about 100 [metres] inside a double row of fixed bayonets with the unknown something to face at the end, caused a marked change in attitude.”

In all, over 200 men were detained on various charges from unlawful assembly to riotous behaviour.

After that the militia spent its time patrolling, backing up the police, making arrests and in basic military training. It was much needed. According to Capt. William Rae of the Seaforth Highlanders, “The chief difficulty at first was [the lack of] experience of soldiering previous to joining the Seaforths. The impossibility of giving any clear understanding of the real meaning of military discipline to men who attend a few drills a year was clearly shown.”

Granted, but in the true Canadian tradition of soldiering, once on active service, the trooper learned fast, aided by the presence of the regular and ex-regulars, both Canadian and British. The Civil Aid Force, all things considered, performed well enough.

By the end of August 1913, civil order had been restored in the strike zone. That led Roy to relay a message to Hall from Bowser ordering the force reduced to 286 all ranks, who carried on the deployment in the same tedious routines. By this point, issues concerning pay and allowances emerged. The pay for a private soldier was $1 a day with a 10-cent hard lying allowance. For a junior officer it was $2.00 plus the 10 cents. The federal minister of Militia, Sir Sam Hughes, was informed that the pay did not cover the cost of maintaining the soldiers’ families. But as expected, Ottawa was indifferent to the financial plight, and the British Columbia government refused to help.

Eight months after the first boots were on the ground, DOC Roy wanted the Civil Aid Force cut to 85 all ranks. He demanded his regulars back and wanted to replace the militia with provincial police. Hall refused. The issue of force reduction began a droll contest between Hall, Roy, Hughes and Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden.

It was all for naught, for as the Judge Advocate General noted, it was not up to them: “There seems to be nothing for it but to repeat to the DOC (Roy) the information that has been given to him so many times before….The dominion Parliament has placed the militia at the disposal of the civil magistrates…and even the Governor General-in-Council cannot interfere with them.”

The troops stayed.

Then on Aug. 15, 1914, a year and a day since the militia were mobilized, the strike collapsed when the UMWA ceased to cover the miners’ strike pay.

Hall wrote, “This closed a duty unique in the history of the Canadian militia for its long duration, its avoidance of forcible action, and the fact it was handled, for the most part by the active militia.”

By that point, Britain had declared war on Germany. Canada was at war. The Civil Aid Force was stood down on Aug. 15, and the men returned home. Most immediately enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force and went to fight, many to die, in Flanders fields.

Advertisement