U.S. Marine veteran John Peck received a double arm transplant recently after losing his arms in combat. [John Peck Journey Organization]

In August, eight years after United States Marine Sergeant John Peck lost his arms and legs in an encounter with an improvised explosive device in Afghanistan, he threw out the first pitch at a baseball game—a feat made possible by a double arm transplant in 2016.

This would have been in the realm of science fiction when Curley Christian, believed to be Canada’s, indeed the Commonwealth’s, only surviving First World War quadruple military amputee, came home, one of some 4,000 who had lost limbs due to military service.

Ethelbert Christian, known throughout life by his nickname Curley, was born in the U.S. in the early 1880s, but emigrated to Manitoba. He enlisted in the Canadian Forces in Selkirk in 1915, and served at the front with the 78th Battalion, known as the Winnipeg Grenadiers.

Credit: USA Today

At Vimy Ridge in 1917, Private Christian was delivering supplies to the front lines when enemy shellfire buried him in a trench beneath rubble and dirt.

He was trapped for two days. Two stretcher-bearers determined he was still alive, but as they carried him off the field, artillery fire killed both. Christian was picked up by a second recovery team.

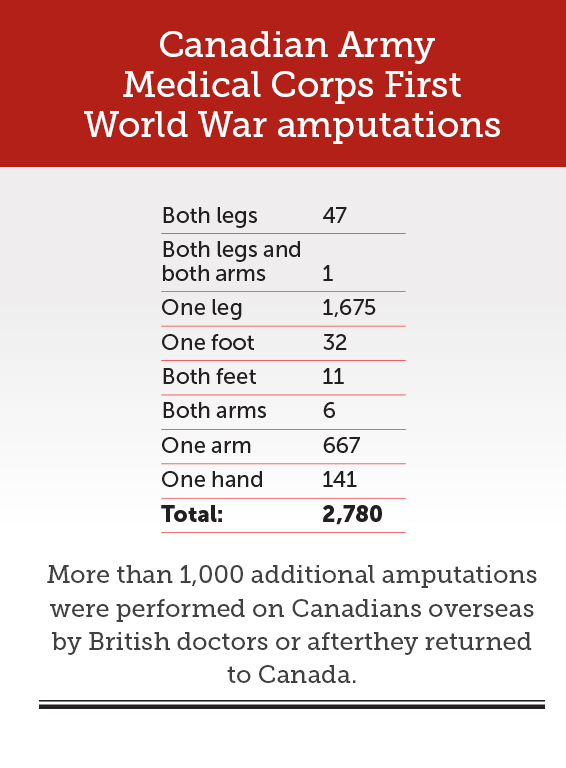

By this time, his wounds had long been exposed to the filth and bacteria in the battlefield dirt, his limbs irreparably damaged from lack of blood. Gangrene had set in. Doctors amputated both legs five inches below the knee, his arms four and five inches below the elbow respectively.

In the age before antibiotics, Christian was not expected to survive this highly risky surgery and perilous recovery. But survive he did.

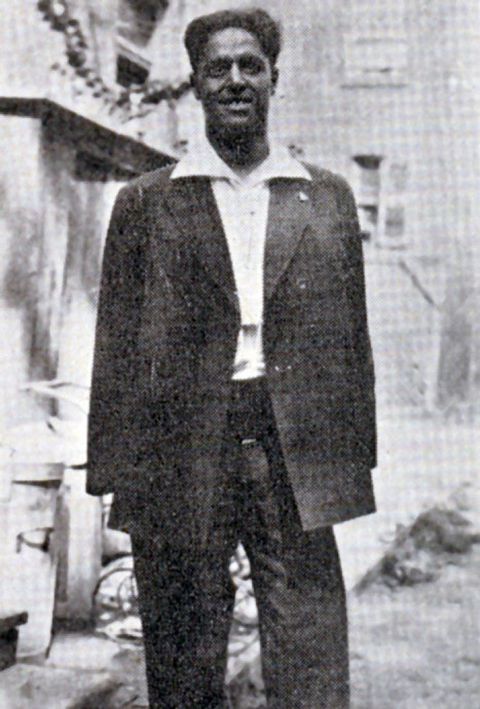

Ethelbert “Curley” Christian lost both his arms and legs after being severely wounded at Vimy Ridge. [THE WAR AMPS OF CANADA]

In September 1917, he was sent home, where he was fitted with prosthetics and began rehabilitation, eventually moving to Euclid Hall in Toronto, the Military Hospitals Commission home for veterans with incurable conditions.

There Christian met his wife, nursing aide Cleopatra McPherson. They married in 1920, settled in Toronto and had a son who served in the navy in the Second World War.

Christian lived a full, if circumscribed, life. His amputations left him unable to pursue his pre-war trade as a chain maker and labourer, but he was by no means a social wallflower. Newspaper accounts in the 1930s describe him as happy-go-lucky and cheerful.

In 1936, he was one of 6,200 Canadian veterans attending the inauguration of the Canadian National Vimy Memorial in France, where he chatted with King Edward VIII and introduced him to blind veterans. He also met King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, who were visiting hospitalized veterans during their 1939 royal tour across Canada.

For years, Christian was in and out of hospital, his wife becoming his full-time caregiver, at grave financial cost to the family. The hospital director argued that it would be cheaper to pay Cleo to care for Christian at home. He launched one of many citizen appeals to the government for financial aid for those supporting severely disabled veterans, often giving up their own source of income to do so. The government finally began paying an allowance to caregivers of veterans disabled by war wounds, the roots of caregiver benefits that survive to this day.

He kept active after rehabilitation, thanks to government-provided prosthetics, contributing to family income by selling cigars, and being a supporter of, and advocate for, veterans.

When it became obvious that private manufacturers could not meet demand for prosthetics, the Military Hospitals Commission took over production, and covered all costs for Canadian veterans, including replacements. Although some prosthetics had specialized attachments for participating in sports, Curley himself developed a specialized attachment for his prosthetic arm that enabled him to write letters of support for, and advice to, other military amputees.

He wrote a letter to the first quadruple amputee of the Korean War, Pte. Robert Smith of the U.S. Army, who lost his hands and both legs in 1950. Wounded in fighting around the Chang-Jin reservoir, Smith lay for three days in bitter November weather, playing dead as Chinese troops stripped off clothing. By the time he was rescued, his hands and legs were frostbitten and surgeons amputated to prevent gangrene.

“You’ll have to get a new outlook,” Christian wrote. “It’s not a question of bravery but a question of facing the situation. It’s a matter of looking forward, not back.

“You’ve got to be wary of sympathy and you’ve got to have patience and a sense of humour,” he advised. “But the greatest secret is to know for sure that God will take care of you.”

An inspiration to generations of Canadian amputees, Christian died in 1954, age 70, and is buried in Prospect Cemetery in Toronto.

Advertisement