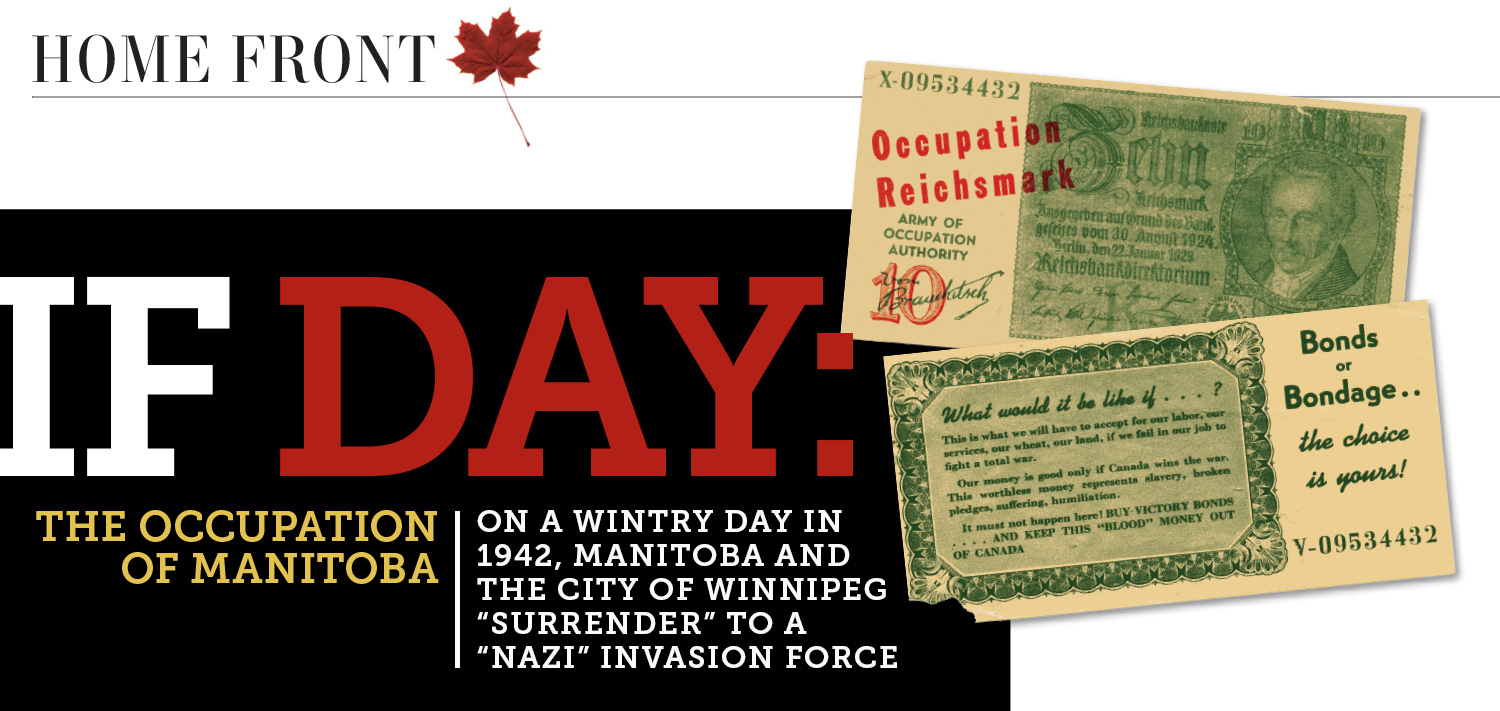

TOP: Currency An “occupation Reichsmark” was used as currency. A notice warns of the consequences of losing the war. BELOW: Raising the flag German soldiers raise the Nazi swastika within the walls of Lower Fort Garry. [Winnipeg Free Press Archives; courtesy of Diane Edgelow]

On the frigid Winnipeg morning of Feb. 19, 1942, Diane Edgelow’s mother sent her out to buy a loaf of bread. She was 12 years old and got the shock of her life when she crossed the bridge into downtown. “They were guarded by German soldiers; they seemed to be everywhere,” she recalls. “I was so scared.” Paying for the bread, she was handed a German Reichsmark in change.

It wasn’t supposed to be a surprise. Two days earlier, the Winnipeg Tribune had run front-page stories of a planned mock Nazi invasion (“Winnipeg to be ‘Occupied’— What would it mean to Manitobans if Nazi hordes spread across the province?”) but not everyone read the daily newspapers. “No one in our house would read the paper,” says Edgelow, now a retired nurse. “I don’t think my mom would have sent me down to the store if she knew there were going to be soldiers dressed like that. Maybe I wouldn’t have been so scared if I had been told before.”

Being scared was part of the intended effect. The operation, the largest military manoeuvre in Winnipeg history, was in support of an effort to boost sales of Victory Bonds, and was widely publicized all over North America. Much of the public had been viewing the war as something far away overseas; bond sales needed a lift. Dubbed ‘If Day’, the exercise was to give Manitobans a taste of what it would be like to give up the everyday civil liberties they take for granted, enticing them to buy bonds to fight the Axis Powers.

The manoeuvres had been planned for months. Realistic German army uniforms were rented from a Hollywood supplier complete with helmets, belts, badges and boots. Donning the outfits and acting as storm troopers were members of the Young Men’s Section of the Winnipeg Board of Trade. “Defending” the city was a mobilized force of 3,500 soldiers drawn equally from active and reserve forces.

It was meticulously designed to be as realistic as possible, affecting all walks of life, particularly those that would suffer under a Nazi regime: homes, shops, schools, churches, restaurants, city hall, libraries, hotels, newspapers, radio stations, even the provincial Legislature. Progress of the invasion and its defence was broadcast throughout the province. Coverage was to be continent-wide: Life magazine, Associated Screen News of Canada, and most major North American newspapers and newsreel organizations were in town anxious to cover every aspect.

The invasion was launched on the morning of If Day with a 7 a.m. siren signalling a blackout. Street lights were shut off and residents doused their lights. Starting from a three-mile perimeter from the city centre, the German troops advanced on the dark city. Artillery first opened fire in East Kildonan. Royal Canadian Air Force aircraft with temporary Luftwaffe insignia flew overhead in mock bombings—to “soften up” resistance. To shoot them down, cars with anti-aircraft guns loaded with blanks boomed from the streets. Fixed ack-ack units were stationed at city hall, the Canadian National Railway depot, Osborne Stadium, and the Paris Building. Smoke pots obscured main intersections where defenders were stopping all cars to check registration cards.

At 7:30 the defenders strategically withdrew to a two-mile ring. But by 8:30 they could no longer hold and 15 minutes later had to further withdraw to bridges and avenues leading to downtown.

As the blitzkrieg advanced towards downtown, nothing was in their way. “I was one of the young guys in the militia,” recalls George Hoffman, then a 19-year-old private with the 1st Cavalry Division Service Corps. He remembers getting up at 4:30 that minus 8-degree morning and being picked up at Minto Barracks. “They stuck us in the suburbs at the cross-streets, out in the boonies more or less, mostly in the residential areas. We were there for awhile.”

Hoffman, now 94, says the “German” forces didn’t take prisoners. “No, in fact we were briefed on what we should and should not do. One of the things we were not to do is get physical with these guys because it was all a big act and we didn’t want anybody to get hurt.”

By 9:30 the attacking forces had overrun most of the defenders. As the overwhelmed defence forces retreated towards downtown, demolition squads launched their scorched-earth policy, setting off dynamite charges to “destroy” bridges including Main, Provencher and Louise, to slow the enemy advance. A deafening explosion blew river debris onto the Norwood Bridge. Great volumes of smoke rose from its centre supports—officially it was blown up and destroyed. The dynamite had actually been placed on the ice near the bridge but it had the intended psychological effect. Rifle fire continued to crackle across the bridges in the breaking dawn.

As the battle progressed, ambulances and converted light delivery trucks brought in the “wounded” to the casualty clearing station in the Dominion Motors building. The only real casualties were a soldier’s sprained ankle and a housewife who had slashed her thumb during the blackout.

After the 9:30 surrender, the Nazis quickly started their work on the citizenry. Churches are stormed, priests arrested, signs posted: “Verboten: It is forbidden to hold services of worship here.” Schools are occupied and teachers arrested. In one school, “Principles of Democracy, Our Way of Life” was erased from the blackboard and orders were given to teach only the Nazi “truth.” Private homes are forcibly entered, pillaged and looted.

The realism continued. Local radio stations commenced broadcasting Adolph Hitler’s speeches and playing martial music. On William Avenue, occupying troops rushed into the library and soon emerged with armloads of books, tossing them into a bonfire, laughing gleefully. “I caught a glimpse of the burning books,” says Hoffman, who was at first alarmed. “But then I read in the paper that these were books the library was going to destroy anyway, so they were used to build this bonfire. But a lot of people didn’t know what was going on.”

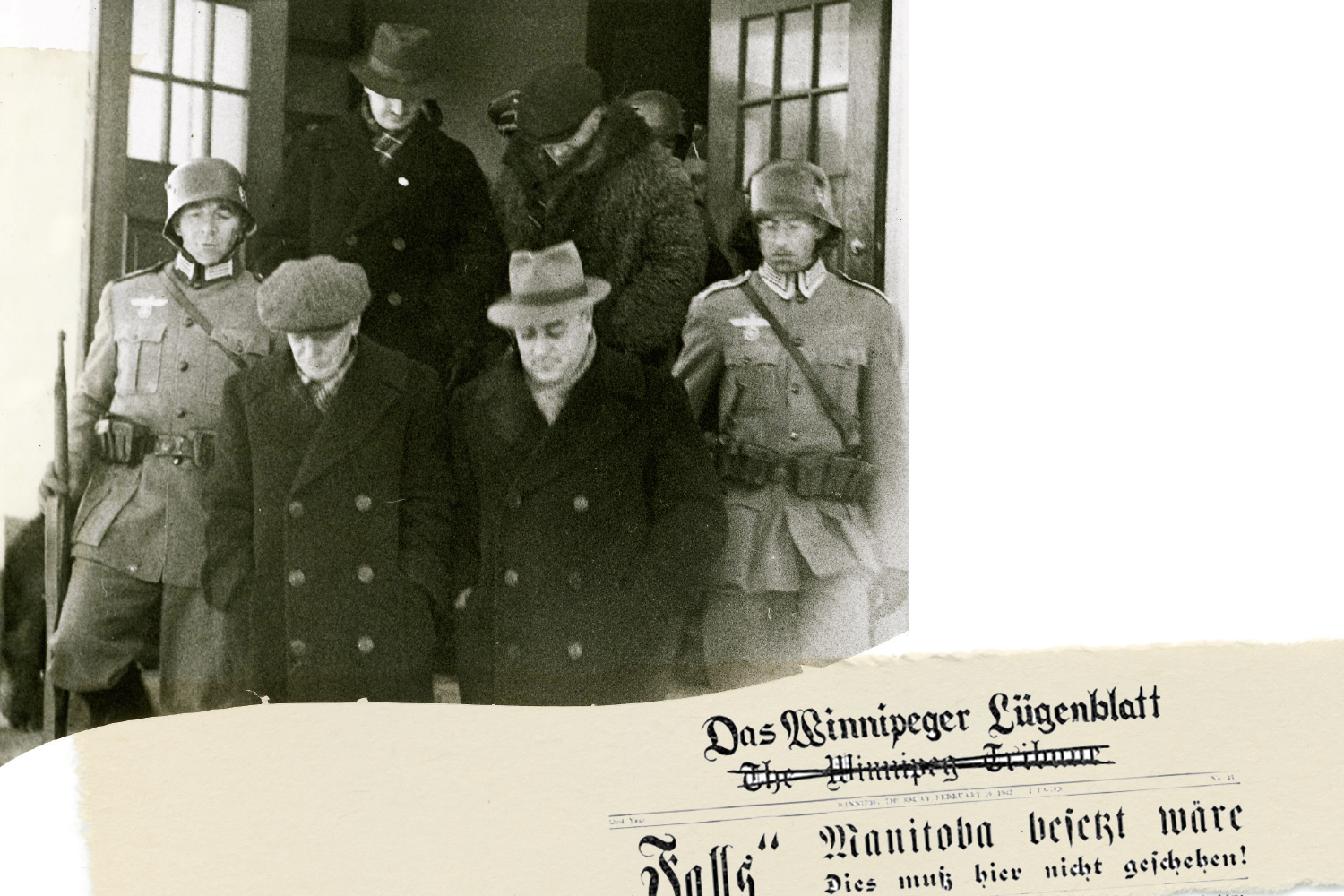

On the street, newspaper vendors were hassled and their papers torn up. The Winnipeg Tribune became Das Winnipeger Lugenblatt.

Then, led by a monocled German officer, six soldiers rushed into the Legislature Building and arrested government officials. Out they came with Lieutenant-Governor R.F. McWilliams, Premier John Bracken, his minister of mines and resources, his attorney-general, his minister of education and four other ministers. At city hall, Winnipeg Mayor John Queen, several aldermen and the city clerk were arrested and imprisoned along with the provincial officials in Lower Fort Garry, commandeered as the German internment centre. The Union Jack was burned and the swastika flag hoisted. Installed in Mayor Queen’s office was a Gauleiter, a regional leader of the Nazi Party, named Colonel Erich von Neuremburg.

Neuremburg set to work immediately, ordering proclamations pasted on telephone poles announcing new restrictions on citizens: a 9:30 nightly curfew, restricted gatherings, enforced home billeting for German soldiers, farmers to report all grain and livestock holdings, and no national emblems may be displayed except the swastika. Organized resistance will mean death without trial. He declared the city would now be known as Himmlerstadt.

Captured Municipal officials (top) in Selkirk, Man., are arrested by German soldiers. The Winnipeg Tribune is renamed Das Winnipeger Lugenblatt. [Winnipeg Free Press Archive; Manitoba History and Historical Documents]

The action wasn’t all confined to the provincial capital—many other Manitoba towns played along. Flin Flon sounded its siren at 7:15 a.m. to announce the advance on Winnipeg and the radio station brought updates on the capital’s battle. Eventually even Flin Flon city hall and the radio station were occupied by “enemy” forces.

Hoffman reckons the operation was realistic enough and effective.

“A lot of people were very uneasy and quite intimidated about this thing,” he says. “Maybe it made them think that it could happen here. They didn’t know how far these Nazis would go. Would they rough the population up? Of course us younger guys had visions of going over and fighting them but at the same time you were a little apprehensive. Anyway it all blew over.”

The following day, the freedom of Manitobans was restored and the city returned to normal. A giant billboard with a map of the province was erected at Portage and Main. It was divided into 45 sections—each one representing $1 million in bonds sold. As the campaign worked towards Manitoba’s $45 million quota, on each section was placed a Union Jack until the entire map was covered. The momentum was unstoppable. The province had beat its quota—a cumulative $47,073,500 was raised. That’s about $658 million in today’s dollars.

For Hoffman, the exercise helped fuel another patriotic reaction. “Two months later in April my buddy and I went down to Minto Barracks where our officer was working and told him we wanted to join the 18th Reconnaissance which was eventually the 12th Manitoba Dragoons,” he said. Posted to Europe, his firefights with Hitler’s troops soon went from shooting blanks on Winnipeg streets to the real thing.

And Diane Edgelow still has her souvenir Reichsmark.

Advertisement