Montrealer Gustave Biéler spent the Christmas of 1943 in France. It was likely to be his last. The Nazis had launched a manhunt for him and his comrades in the French Resistance. The spy, known only by his code name Guy, wrote a few lines on the back of a photograph and handed it to his host, Camille Boury. “If misfortune overtakes me some day, write to this address.” His pre-war employer could contact Biéler’s wife, whose name was also kept secret, to prevent reprisals against family. “Tell her how I spent Christmas…tell her how I thought of them.”

Three weeks later, the Nazis did catch him. They tortured him for information, and when he gave none, tortured him some more. For months. They beat him, broke a kneecap, nearly drowned him. Sent him to Flossenbürg concentration camp in Germany where he was kept in solitary confinement in the dark, starved and beaten some more. He never gave them so much as his own name.

On Sept. 9, 1944, D-Day past, Paris and Rome liberated, the Allies beginning their long slog from the Netherlands to Berlin, the man known only as Guy the Canadian limped to his death, accompanied by a German honour guard.

Members of the French Maquis, rural resistance fighters, confer in La Trésorerie. [Jacqueline Biéler]

He was killed by firing squad, this quick death a measure of respect. Fellow Canadian spies captured before they even had a chance to go to work were sadistically murdered, a horror ordered from on high. Heinrich Himmler, leader of the dreaded SS (Schutzstaffel), which ran Nazi concentration and extermination camps, said all spies should be killed “but not before torture, indignity and interrogation had drained from them the last shred and scintilla of evidence which should lead to the arrest of others. Then, and only then, should the blessed release of death be granted them.” The means used were more often murder than execution.

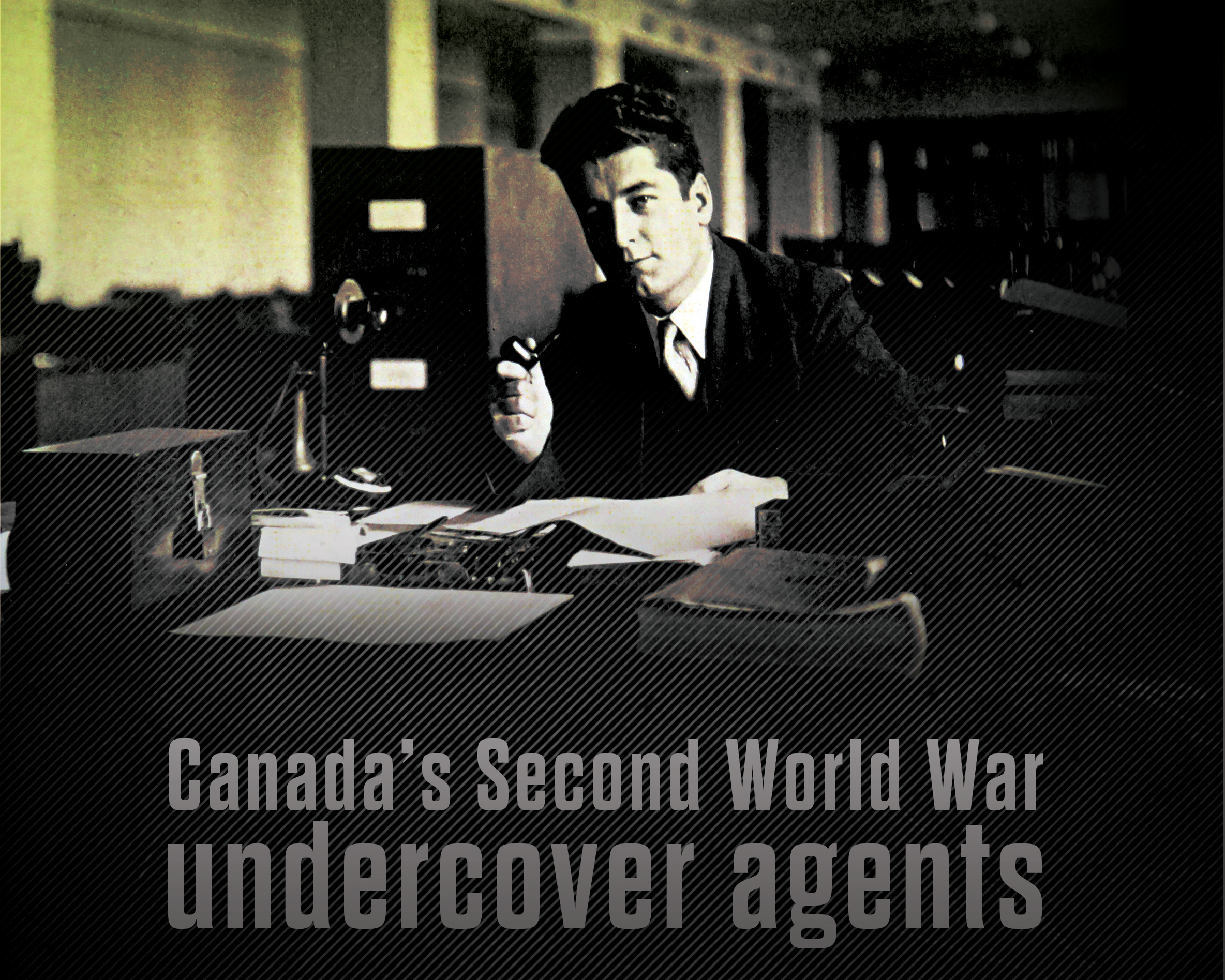

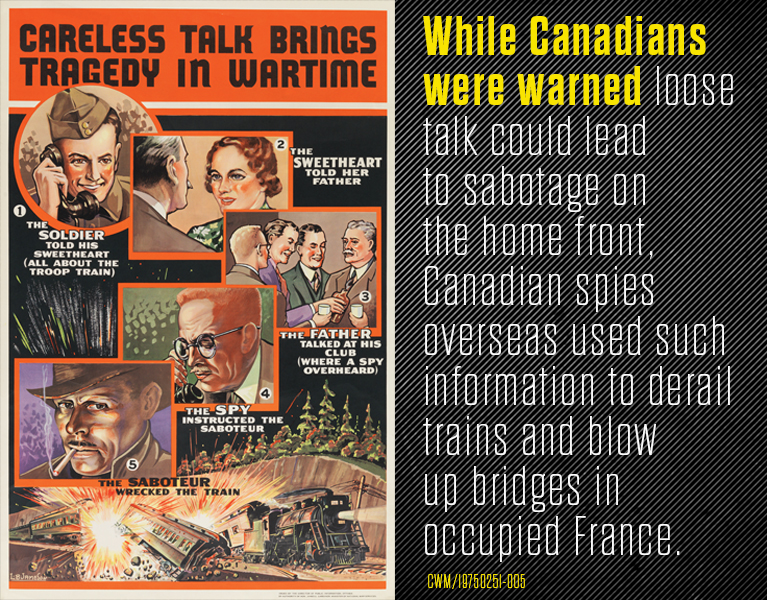

Despite constant danger, with torture and death distinct possibilities, Biéler was among some 200 Canadians who volunteered to become undercover operatives working behind enemy lines in Europe and Asia in the Second World War.

“You cannot permit what these Germans are doing to spread,” Biéler told a friend.

“He had a deep sense of duty,” said his daughter Jacqueline Biéler of Ottawa, who has spent much of her adult life collecting documents about her father, who left when she was so young that she has no clear memory of him.

Biéler, a translator for an insurance company in Montreal, was born in France and raised in Switzerland. He became a teenager during the First World War, was familiar with its dreadful toll in France: 1.4 million dead and six million casualties overall, ghost villages obliterated by shellfire.

Biéler emigrated to Canada in 1924, became a citizen a decade later, married and had two children. But with a brother in Paris and a sister in London, he had more than passing interest—and alarm—at the rise of Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Party in Germany. When war was declared, he started officer training school, and went to England with the Régiment de Maisonneuve in 1940, eventually becoming their intelligence officer.

By the summer of 1940, times were desperate for Britain. There was a serious threat of invasion. The Nazi juggernaut had rolled over France as it had over Czechoslovakia, Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway and Poland. Supply ships were under relentless attack and food rationing had begun.

While the British battled the enemy by air and sea and prepared with the Allies for an eventual invasion to liberate Europe, what could be done on the ground? They looked to a secret army—citizens in occupied countries. “We have got to organize movements in enemy-occupied territory comparable to the Sinn Fein movement in Ireland, to the Chinese guerillas now operating against Japan…to the organizations which the Nazis themselves have developed,” wrote Hugh Dalton, the British minister for economic warfare. Patriots and rebels could disrupt supply lines and communications, tie up enemy manpower by the need for security, policing, manhunts and guarding prisoners. They could report on enemy movement, help military personnel and civilians stranded behind enemy lines to escape, and take up arms when liberating armies arrived. The British set up two secret organizations to organize, train and supply them—the Special Operations Executive (SOE) and MI9 (Directorate of Military Intelligence, Section 9).

The SOE established networks in occupied countries to conduct sabotage and gather intelligence. One report estimated “tens and even hundreds of thousands” in France were willing to fight against oppression, and three resistance groups had already formed. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill briefly summed up SOE’s mission: “Set Europe ablaze.”

Few people had the right stuff to be agents for either organization. Their safety depended on blending in with the local population, so each agent needed to be familiar with an occupied country and fluent in its language. But they also needed tough minds, hard bodies, the skills to set up and run networks and the discretion to keep them secret. They had to have stamina, courage and the ability to think on their feet and on the run. They needed the resolve to carry on under constant threat of capture, torture and death.

SOE had four sections that accounted for some 1,800 operatives sent to France between 1941 and 1944. The independent French Section—Section F—sent in nearly 500 agents and was always short of French-speaking wireless operators. And there were also shortages of agents able to speak the languages of Eastern Europe. Canada’s immigrant population and French Canadians provided a ready pool of candidates for the two covert operations. Civilian and military candidates were sifted for applicable skills and characteristics, and the best were sent for rigorous training in facilities across Britain.

Several dozen were screened, selected and given initial training at Camp X, the secret spy school in Ontario run by Sir William Stephenson, code-named Intrepid. “We were trained to live by our wits, in any circumstance,” said Joe Gelleny, a Hungarian Canadian SOE recruited out of the Canadian Army. They learned to load, fire, dismantle and reassemble guns, how to handle explosives. “We learned how to kill a person a dozen ways, including how to do it without your victim being able to make a sound.”

Biéler, who spoke French with a European accent and was already familiar with intelligence work, was a prize catch. He was recruited in England in 1942, the first Canadian SOE volunteer to serve in the field. That year Raymond LaBrosse of the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals became MI9’s first Canadian recruit.

Training for those with assignments in Europe began with commando school in remote Arisaig, Scotland, soon referred to as “the Looney Bin” for the bizarre psychological testing, said Guy d’Artois, of Richmond, Que., a commando with the Canadian-American First Special Service Force, sometimes called the Devil’s Brigade, before he was recruited by SOE. At Arisaig and other “schools” recruits learned commando tactics, weaponry, silent killing, evasion techniques. At “cookery school” they learned how to handle, make and set explosives.

Gelleny’s skills were put to the test in Hungary, where he was captured and tortured, freed by Hungarians, recaptured by the Germans, escaped again, and captured by the Russians at the end of the war. Persuading his captors he was British, he was allowed to rejoin the Allies, 230 kilometres away.

But he had to walk.

SOE agents learned how to parachute from aircraft, use Morse code, organize a saboteur group, and communicate with handlers in Britain. They were given code names, cover stories, false identity papers, and taught how to avoid detection (including language training: a French Canadian accent might not give them away, but using Canadian expressions would). They were also advised to keep silent for 48 hours after capture to give other members of their networks time to escape. MI9 agents were outfitted with clandestine equipment such as fountain pens that fired tear gas,

buttons concealing compasses and silk maps.

Canadian officers who served as Special Operations Executive agents arrive home in December 1944: (front, from left) Lieut. J.E. Fournier, Lieut. P.E. Thibeault, Capt. H.A. Benoit; (rear) Major P.E. Labelle, Capt. L.J. Taschereau, Capt. Guy Artois, Capt. J.P. Archambault. [LAC/PA-213624]

Biéler was adept at it all. One commanding officer wrote he was “the best student we’ve had…conscientious, keen, intelligent, a sound judge of character; good-natured, absolutely reliable, outstandingly thorough, a born organizer.” Agent Gabriel Chartrand, a friend Biéler had recruited for SOE, was told “if you’re half as good as Guy, you’ll be magnificent.” And Chartrand needed to be; his networks were betrayed several times, forcing him to switch identities. Once, after delivering an American pilot to an escape network, Chartrand was arrested, threw his bicycle at his captor and dodged a hail of bullets, escaping from two Gestapo agents.

Biéler was, Chartrand said, “the great Canadian war hero.”

Biéler was in pain from the moment he parachuted into France Nov. 18, 1942, when he seriously injured his back on landing. SOE offered to transport him back to Britain, but Biéler insisted on staying. He spent six weeks in hospital under a false identity, then began organizing his network, code-named Musician, while recuperating at the home of Eugène Cordelette, leader of a French resistance unit. Musician was one of the most successful SOE networks. Centred in Saint-Quentin, 130 kilometres northeast of Paris, Musician teams disrupted the transportation hub where war matériel was shipped from French industrial centres to supply the German army, navy and air force.

Musician teams derailed a score of trains. “We called it the big smash-up,” resistance member Raymond Bezin said in a 2005 documentary. “We would unbolt and remove the tracks so the trains would derail and fall over.” They wrecked an engine repair shop and a dozen locomotives, and damaged another score with abrasive lubricant. They cut the main rail line from Saint-Quentin to Lille every other week and the Paris-Cologne line a dozen times.

Held in high esteem by his trainers and handlers, le Commandant Guy was also loved by the French, as his daughter Jacqueline discovered on trips to France decades later. Streets were named after him, and people fondly remembered him. “My father had a very easy personality,” she said. “He was very friendly, easy-going, jokey. He made friends easily.”

He is especially remembered for the care he took to ensure the safety of innocent people. He once refused an assignment to target a munitions train on a siding next to some houses, said Cordelette, because too many civilians could be killed or injured.

After air force bombing of a train engine factory in Denain, where about 30 civilians had been killed, Biéler pleaded with London to let his teams handle such demolition in future, for they could be more precise in destroying targets. He demonstrated this after bombers failed to damage canals down which supplies, including parts for U-boats, were transported. Biéler and two members of the resistance hid themselves in a punt and drifted undetected down a canal to place bombs below the waterline on a lock gate. They later took out 40 barges loaded with parts for U-boats. It took the Germans weeks to reopen the canal.

“He visited many families,” said his daughter. “And he would always tell them to lock the door. If the Gestapo came, he would find another way out, so he would not be found in their company.”

The penalty for aiding the Allies was dire, not just for members of the resistance, but their families and communities. SOE refused to let d’Artois and fellow agent and future wife Sonia Butt work together, because they knew the Gestapo forced unco-operative captured resistance members to watch as family members were tortured. Whole communities could be punished, too. On June 10, 1944, in retaliation for activities by a resistance cell in a neighbouring village, 190 men of Oradour-sur-Glane were rounded up in barns by the SS, shot in the legs, their bodies doused with gasoline, and set afire. The village’s 247 women and 205 children were herded into the church, which was torched. Those who tried to escape were machine-gunned. The village was then set on fire. (The ruins have been preserved as a memorial to the massacre).

“Every minute when you’re a secret agent is dangerous,” surviving spy Allyre Sirois said in the 2005 documentary. Everyone recruited for undercover work behind enemy lines was told capture would mean torture and certain death. “They warned me it could be dangerous. I was prepared to take that chance. I was determined to get rid of the Nazis.”

Despite every precaution to keep identities safe, Biéler knew there were collaborators, double-agents and plenty of scared people willing to turn in his team in order to save themselves. His luck ran out Jan 15, 1944. Biéler and his radio operator were arrested at a café in Saint-Quentin, followed by nearly 50 of Musician’s members. But the careful Biéler had taken precautions when setting up the network. The identities of members of Musician’s 25 teams were unknown even to each other, so some of those teams remained undetected and were active right up to D-Day, when they took part in the fight for liberation, using arms delivered by parachute drops Biéler had organized.

Among those rounded up was Cordelette, Biéler’s host while recuperating from his back injury, who saw Biéler in Saint-Quentin Prison just after their arrest. “He was chained hand and foot. His face was horribly swollen, but I could read in his eyes this order: ‘Whatever happens, don’t talk!’ In spite of all torments, he showed no weakness.”

Consequences were dire when a network was blown. In 1943, Frank Pickersgill, of Winnipeg, and his radio operator John Macalister, a Rhodes Scholar from Guelph, Ont., were parachuted into France to join a network which had been penetrated by a double agent. Within a week they were arrested by the Gestapo. Messages they were carrying to SOE agents were discovered, along with Macalister’s radio sets, codes and security checks. Hundreds of resistance members and dozens of agents were subsequently rounded up, and 425 tonnes of arms and explosives captured. The Germans pretended to be Pickersgill for 10 months, using Macalister’s radio to order drops of arms, supplies, money and agents, who were seized as they landed and sent for interrogation and execution. Only weeks after Paris was liberated, Pickersgill and Macalister and 14 other agents were hanged from meat hooks and slowly strangled to death with piano wire at Buchenwald concentration camp.

MI9 agents were in no less danger, though escape and evasion, and not sabotage, were their specialties. Allied air force officials estimated that by 1943, air crew parachuting into occupied territory had a 50 per cent chance of getting out safely. After the war, it was estimated that escape networks helped several hundred soldiers and about 5,000 air crew. Air crews were told to seek out a church if they went down behind enemy lines, because priests could be relied upon to help. Or to go to an isolated farm. Or to approach a railway porter on a train.

Sometimes evaders were immediately turned over to the Germans, but most often they were passed along to an escape network. Initial reports about the number of citizens in occupied France willing to help were not exaggerated. Local people provided safe places for evaders to hide, sometimes for several months, and supplied clothing and food, rationed at the time. They found doctors willing to secretly treat the sick and wounded. Downed air crew had to be moved by train from one place to another, so had to be coached on how to blend in. Locals passed escapers from one hiding place to another and guided thousands through occupied territory to safety. If caught, they faced the same certainty of torture and death as the spies. And they risked the lives of their families, too. One source says one escape- line worker died for every person led to safety.

Despite the risks, SOE’s Allyre Sirois, only 20, was hidden for three months by the resistance after his network was betrayed by someone bribed by the Gestapo.

Raymond LaBrosse’s mettle was tested in early June 1943, when the network in Brittany was blown and its operations chief and 57 hidden air crew were arrested. LaBrosse had to escape, and he took the terrible risk of leading 29 remaining fugitive air crew with him, south from Brittany, through occupied France, across the Pyrenees and into Spain, then Gibraltar.

Safe in London, LaBrosse volunteered to go back into occupied France to set up another escape route in Brittany. He was teamed with Montrealer Lucien Dumais, who had been among the nearly 2,000 captured after the debacle at Dieppe in August 1942. Dumais escaped, jumping from a train taking the prisoners to Germany, and made his way to Gibraltar with help from the resistance and friendly French people.

Together, LaBrosse and Dumais parachuted back into France on Nov. 19, 1943, where they established the Shelburne Line, one of MI9’s most successful evacuation routes, credited for saving more than 300 Allied airmen.

“It was a risky business,” said LaBrosse. “You were not going into France to blow up a bridge with only a few people in the know. You were dealing with bodies, human bodies with human problems. How do you keep, say, 75 airmen tucked away in Paris for a considerable period of time? How do you do it without anybody knowing about it and how do you move them from there to point A or B? You’re always out in the open, subject to enemy control. You had to depend upon other people for help in feeding, clothing, guiding the airmen. It had therefore to be a big organization, but the bigger it was the more likely it was to be penetrated.”

Casual discovery was also a problem, particularly in the early days when LaBrosse had to carry his radio equipment with him. Every time he used it, he risked being picked up by German direction-finding equipment.

Safe houses and networks of resistance workers were needed at both ends of the line: in Paris, where evaders were gathered and hidden until they could be safely moved, and in Brittany, where the “packages” were picked up on moonless nights from a secluded beach near Plouha, about 480 kilometres west of Paris. Groups of evaders travelled from city to city by train—often in the same car as German soldiers, and at every station, under the watchful eye of guards who could demand identity papers at any moment.

But the line was working like a well-oiled machine on March 16, 1944, when pilot Ken Woodhouse, from Prince Albert, Sask., bailed out of his plummeting Spitfire 100 kilometres north of Paris. A passing farmer, a member of the resistance, hid him in a pile of hay in the back of his truck and misdirected an inquiring German patrol. The pilot was hidden in a safe house, given identity papers and, along with six Americans, put on the train to Paris two days later. They arrived just as hundreds of German soldiers were leaving a troop train; the overwhelmed Gestapo agent didn’t check their papers.

Woodhouse was moved from safe house to safe house in Paris. He was given new papers, and finally joined a group being guided from Paris to Brittany, likely led by resistance member Mirielle Herveic whom Woodhouse described as “audacious ingenuity at its frightening best.” Security along the coast was tight, and when German soldiers on the train began questioning her, Herveic flummoxed them by replying in sign language. In Brittany, the group passed through several more safe houses before being guided down a cliff, led through a minefield on the beach, and picked up and taken by boat to England. Astonished comrades at Biggin Hill air base welcomed Woodhouse back a mere 10 days after his aircraft was lost.

After the war, Biéler’s Christmas wish was carried out. Camille Boury did contact Bieler’s wife Marguerite (née Geymonat), who had worked during the war for Radio Canada International, broadcasting to troops in Europe. “They corresponded for years,” said Biéler’s daughter Jacqueline.

Every Canadian SOE operative captured by the Nazis was killed, but there were many successes. “Canadian-led efforts seriously hindered the ability of the 1st and 2nd Panzer Divisions to intervene in Normandy,” after D-Day, Sean Maloney reported in the Canadian Military Journal in 2003. Canadian-led operations also harried the logistic structures supporting the V-1 and V-2 blitz against London in 1944.

The Chiefs of Staff said the 750,000 partisans supported by SOE in Europe and the Balkans alone “created a substantive military problem for the Germans.” U.S. General Dwight Eisenhower was blunt: “The Resistance in France shortened the war [in Europe] by nine months.”

These spies worked and sacrificed in anonymity; secret agents don’t keep field notes, and many records were destroyed after the war. There remain few records and only a few people who can tell the stories of Canada’s hush-hush heroes.

Top photo: Gustave Biéler: was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Order and Most Excellent Order of the British Empire for his work behind the lines in France.

Advertisement