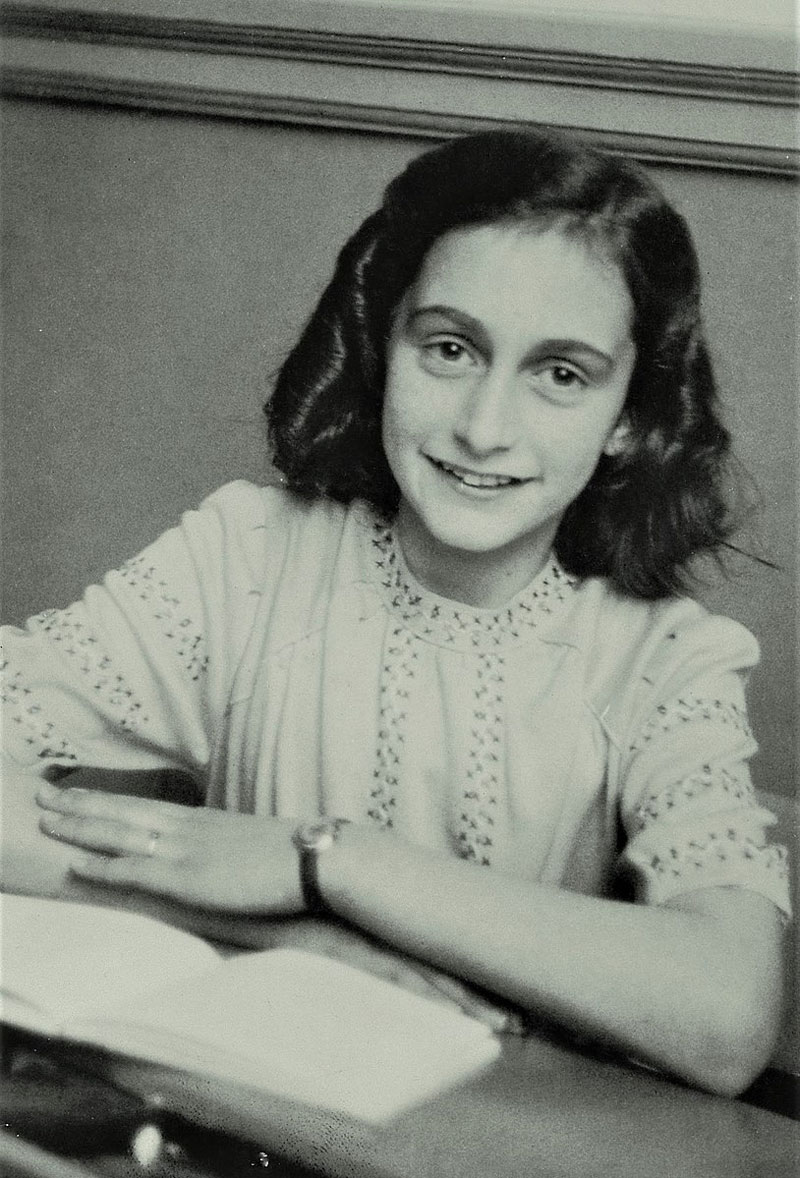

Anne Frank’s diary, written over two years while her family was in hiding, was first published in 1947. It’s since been translated into over 70 languages and read by millions. [Wikimedia]

Ambo Anthos, Amsterdam-based publishers of The Betrayal of Anne Frank: A Cold Case Investigation, sent an e-mail to the book’s Canadian author and the investigators who spent six years gathering evidence, saying the study’s principal findings need another look.

“A more critical stance could have been taken here,” director Tanja Hendriks said in the e-mail. “We await the answers from the researchers to the questions that have emerged and are delaying the decision to print another run.

“We offer our sincere apologies to anyone who might feel offended by the book.”

The book’s English-language publishers, HarperCollins, declined comment. The American publishing house financed the project along with a grant from the City of Amsterdam.

The team of historians and investigative experts said it’s likely Arnold van den Bergh, a Jewish notary in Amsterdam, gave up the Franks to save his own family. The accusation spawned a firestorm of criticism from others close to the story who contend there’s not enough evidence to reach such conclusions.

Van den Bergh was a member of the city’s Jewish Council, which implemented Nazi policy in Jewish areas. The council was disbanded in 1943 and many of its members were said to have been sent to concentration camps.

But the research team, assembled six years ago by Dutch media producer Pieter van Twisk and headed by an ex-FBI agent, discovered van den Bergh was not sent to a camp, and instead continued living in Amsterdam.

The six-year probe by a team of historians and professional investigators identified Arnold van den Bergh, a Jewish notary in Amsterdam, as the person who gave up the Franks to Nazi authorities. [Wikimedia]

The team acknowledged it had struggled with the revelation that another Jew was possibly the betrayer but said it found evidence suggesting Otto Frank, Anne’s father, knew van den Bergh had given them up and kept it secret.

The investigators found a copy of an anonymous note sent in 1945 to Otto Frank, the only family member to survive the Nazi concentration camps. It identified his betrayer as van den Bergh, who reportedly died of throat cancer in 1950.

Anne’s father turned the note over to a Dutch detective who conducted an investigation in 1963, but the detective dismissed it.

The 298-page book, written by Canadian poet, biographer and anthologist Rosemary Sullivan, reached number 1 on the Toronto Star’s bestseller list, even as it was met with scepticism and consternation in some quarters.

David Barnouw, author of the 2003 book Who Betrayed Anne Frank?, was among several Dutch historians who voiced concerns about the findings by van Twisk’s team. Barnouw said he had initially identified van den Bergh as a suspect but later ruled him out because he found no evidence of his involvement beyond the note.

Emile Schrijver, director of Amsterdam’s Jewish Cultural Quarter, told The New York Times the evidence contained in the book is “far too thin to accuse someone.”

“Big conclusions demand big proof.”

“This is an enormous accusation that they made using a load of assumptions,” Schrijver added, “but it’s really based on nothing more than a snippet of information.”

“They came up with new information that needs to be investigated further, but there’s absolutely no basis for a conclusion,” said Ronald Leopold, executive director of the Amsterdam museum at Anne Frank House, where the 13-year-old and her family hid in a secret annex from July 6, 1942, until they were caught Aug. 4, 1944.

Leopold said the museum would not present the findings as fact, but perhaps as one of several theories formulated over the years.

“Big conclusions demand big proof,” historian Johannes Houwink ten Cate told The Times of Israel. “I cannot believe that a member of the Jewish Council traded addresses for freedom. After the council was abolished, its members were sent to camps, if they did not go into hiding.”

Houwink ten Cate, professor emeritus of Holocaust studies at the University of Amsterdam, spent decades researching Germany’s wartime occupation of the city. He said van den Bergh was in hiding throughout most of 1944, including at the time of the raid by German police, led by an SS intelligence officer.

“Van den Bergh’s special status [as a council member] had been withdrawn by the Nazis,” said Houwink ten Cate. “If he had betrayed the Frank family, he had to come out into the open, and that exactly was what he was trying to prevent.”

All of the Dutch historians interviewed by The Times of Israel expressed disappointment that resources were used on an investigation that produced what one researcher characterized as “rubbish.”

“Above all, the book is full of terms such as ‘most likely,’ ‘most certainly,’ and ‘it is plausible that,’ yet in the end the findings are presented as some kind of truth,” said Laurien Vastenhout, a researcher and lecturer at Amsterdam’s National Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies. “Luckily, by now, some more critical remarks have been voiced.”

Anne loved writing and wanted to be a journalist. [Wikimedia]

Since the war itself, the Jewish Council has been criticized for collaborating with Nazis after the May 1940 invasion and subsequent occupation of the Netherlands.

Some of its members were put on trial after the Holocaust, including van den Bergh, who acted as notary in the forced sale of artworks to prominent Nazis such as Hermann Göring. Houwink ten Cate said it has never been demonstrated that the council possessed lists of Jewish hiding places.

“The very notion that the Jewish Council had lists of hiding addresses is not proven, known, or shown,” said Annemiek Gringold, curator at the Dutch National Holocaust Museum. “All experts I heard until now confirm this is not true.”

Bart van der Boom of Leiden University, whose new book on the council comes out in April 2022, said the premise “makes no sense and is not supported by any serious evidence.”

“If the leaders of the Jewish Council compiled these lists to save themselves, as the book claims,” he said, “why then were they not used in the summer of 1943, when the Jewish Council was dismantled?”

The Franks were among 300,000 Jews who fled Hitler’s Germany between 1933 and 1939.

For her 13th birthday in June 1942, Anneliese Frank was given a locked autograph book bound in red-and-white checkered cloth. She began writing in it soon after and continued throughout her family’s two-year retreat to the three-storey annex above her father’s canal-side warehouse, its entrance hidden behind a bookcase.

“I want to go on living even after my death!”

The young girl wrote about Nazi restrictions on Dutch Jews, the dedication of the four employees who cared for them in spite of the threat of execution should they be discovered, her aspirations of becoming a journalist and the complex relationships an adolescent girl had with her sister and parents.

Her writings evolved into explorations of deeply personal feelings with which virtually any adolescent could identify—beliefs, frustrations, dreams and ambitions, along with more abstract subjects such as her faith and how she defined human nature.

“I want to be useful or bring enjoyment to all people, even those I’ve never met,” she wrote on April 5, 1944. “I want to go on living even after my death!

“When I write I can shake off all my cares. My sorrow disappears, my spirits are revived! But, and that’s a big question, will I ever be able to write something great, will I ever become a journalist or a writer?”

She penned regular instalments until her last entry on Aug. 1, 1944, days before she and her family, along with two other families who had joined them in hiding, were arrested and deported.

Jewish families await deportation aboard boxcars. More than six million are believed to have died during Hitler’s occupation of Europe. [Wikimedia]

Otto Frank was believed to have had a strong suspicion of their identity.

Her father returned to Amsterdam after the war and found that Anne’s diary had been saved by his secretary, Miep Gies. Fulfilling her wish to become a writer, he had the document published in 1947. Otto Frank died in 1980.

The book was translated from its original Dutch and first published in English in 1952 as The Diary of a Young Girl. It has since been translated into more than 70 languages and read by millions the world over.

The mystery of who pointed the Nazis to the annex has remained unsolved for eight decades. Otto Frank was believed to have had a strong suspicion of their identity but he never divulged it in public.

A few years after the war, Otto Frank told Dutch journalist Friso Endt that the family had been betrayed by a member of the Jewish community.

Some two dozen investigators and historians were hired for van Twisk’s project. The New York Times said high-tech tools played a minimal role in their findings, and that their conclusions were reached largely through re-examining old leads.

Sullivan, a Montreal-area native and professor emerita at the University of Toronto, was contracted to write the book.

“The anonymous note did not identify Otto Frank,” she told The Guardian newspaper. “It said ‘your address was betrayed.’ So, in fact, what had happened was van den Bergh was able to get a number of addresses of Jews in hiding.

“And it was those addresses with no names attached and no guarantee that the Jews were still hiding at those addresses. That’s what he gave over to save his skin, if you want, but to save himself and his family. Personally, I think he is a tragic figure.”

She acknowledged the team’s “shocking” findings and that the theory that the Franks were betrayed by another Jew might disturb people.

“Everyone knew how powerful—and upsetting—their conclusions would be; they’re braced for the world’s reaction.”

Advertisement