Green-clad Fenian raiders attack ill-prepared Canadian militia at Ridgeway, near Lake Erie in Canada West, on June 2, 1866. [Library of Congress]

It is a largely forgotten battle, even though it was one of the few ever fought on Canadian soil. By the standards of the time, it wasn’t an enormous fight in terms of lives lost or duration. Coming as it did in the shadow of the American Civil War and one year before Confederation, the Battle of Ridgeway had a significant, underappreciated impact on Canadian history. Growing up in Welland, Ont., I didn’t know much about it, I confess, despite driving past Limestone Ridge literally thousands of times. I knew nothing of my personal connection to the event until a cousin inadvertently discovered a newspaper article from the 1920s referring to an ancestor who, like the battle itself, had been largely forgotten.

The long, lonely whistle of an approaching train was the first inkling villagers had that the battle was moving toward them. Even before they saw the train appear from behind the cedar and dogwood forests to the west, they knew it signalled the arrival of Canadian militia troops. It was June 2, 1866.

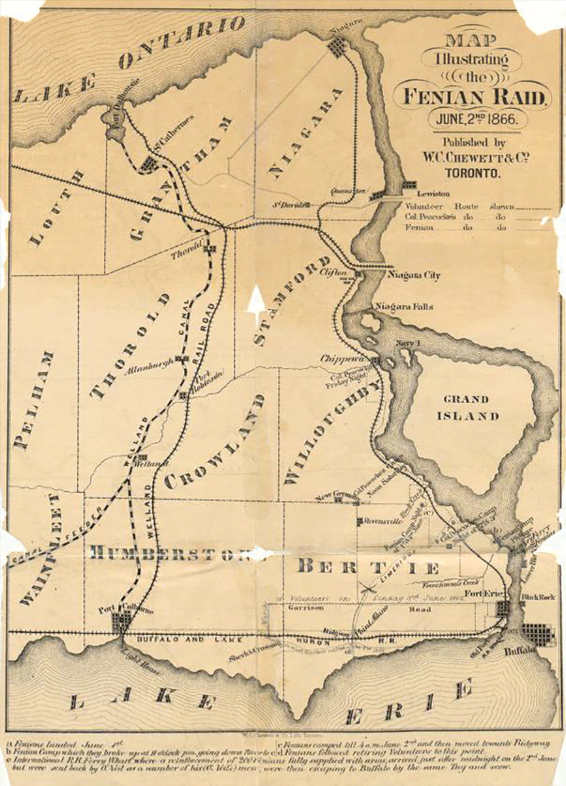

Many rumours had circulated since Fenian raiders crossed the Niagara River the day before. But like spectres, the Irish Republican militants had remained ethereal and elusive. As many as 1,350 of them—who believed the path for a truly independent Irish Republic lay in the “liberation” of Canada—were thought to be somewhere north of the village of Ridgeway that morning.

Almost all the invaders were battle-hardened veterans of the American Civil War who had clearly not had their fill of horror in the preceding years.

That brutal war was only nine months in when my great-great-grandfather, Nathanial Brewster, fell in love and moved his life to that sleepy, little patch of sun-baked sand dunes and waveless green fields. Ridgeway, on the northeastern shore of Lake Erie, was a stone’s throw from the United States border. Just far enough into Canada West to be an escape, but not so far that he could be considered thoroughly disloyal to the republic.

Originally from the even sleepier village of Ellisburg, N.Y., on the eastern tip of Lake Ontario, Brewster had served as a surgeon and a surgeon’s assistant for three years aboard Union gunboats during the bitter contest between North and South. He had survived several desperate encounters. He knew what war looked like and sounded like.

He had married a well-to-do Canadian woman early in 1862 and chose to settle in what was still—for all intents and purposes—a British possession, albeit a responsibly governed one. The politics of the time made it an unusual choice. Britain had been sympathetic to the south’s Confederate States, earning the distrust, even outright revulsion, of the badly mauled Union.

The sound of the train whistle that morning prompted Brewster to pack his surgeon’s kit. He knew what was coming. He arrived at the platform just as the troops dismounted the rail cars which they had been packed into early the night before. To his astonishment, he discovered the soldiers had not been fed.

“I went along their line of march and asked our people to bring out for them all the cooked food on hand,” he wrote in a December 1911 article for the Ridgeway Historical Society. “They responded liberally; and so many of the solders got at least a lunch. I never learned who was in fault, but surely someone blundered, that men were sent into battle without food in this part of the country.”

In hindsight, it was not surprising.

The Canadians arrived without any wagons to carry stores. Unable to find enough transport in Ridgeway, those in charge of the expedition ordered the train back

to the marshalling point, about 20 kilometres west, to collect some.

There appeared to be, in the doctor’s eyes, a great deal of confusion, hubris and hastiness among those commanding the inexperienced militia units. His assessment was supported in later, more formal accounts of the operation.

Intelligence on the militants’ movement since their bloodless capture of Fort Erie, 10 kilometres to the east, seemed to have been based on the testimony of a single, petrified border officer. The man had fled all the way to Port Colborne, where Canadian troops had initially deployed to defend what provincial authorities believed to be the real objective of the Fenians—the Welland Canal. Plans to repel them were concocted and then contradicted throughout that first frantic day.

Even worse, the officer in charge of the all-volunteer force that detrained in Ridgeway had never commanded a brigade in his life. Yet, through a variety of circumstances and impetuous schemes, Lieutenant-Colonel Alfred Booker found himself in Ridgeway in charge of not only his regiment but other troops as well, including the Queen’s Own Rifles.

Booker was thrown into position on the morning of the battle “without any staff, without any mounted orderlies, without artillery, or cavalry,” according to a largely face-saving account written in the fall of 1866 by militia officer Major George Denison.

A well-regarded, long-serving officer, Booker was ordered to march north from Ridgeway toward the rustic village of Stevensville. There he would link up with the rest of the Canadian militia force, which had camped in Chippawa along the Niagara River and was expected to probe southwest. The idea was that the Canadians—once aligned—would contain and then drive the militants out of the province. Booker was ordered to avoid contact with the Fenians until the two forces were combined.

There were, however, miscues. The Canadians, many of them students at the University of Toronto, left Ridgeway in such haste that many of their great coats, standard attire at the time, were left scattered on the train platform.

A telegram from the colonel in overall command of the Canadian expedition, urging Booker to delay his march for an hour, was hand-delivered only after they left, according to Denison. Regardless, the brigade didn’t get very far.

“About an hour after the troops marched away, the sounds of battle so familiar to my ears were heard and I again went among the people and told them there was fighting going on down there, and there would soon be wounded to care for and advised them how to prepare for their reception,” said Brewster.

He struck out on the road toward the unseen contest. In his surgeon’s kit, he carried his “instruments, bandages, adhesive plaster, chloroform, a canteen full of whiskey, [and] another of water.”

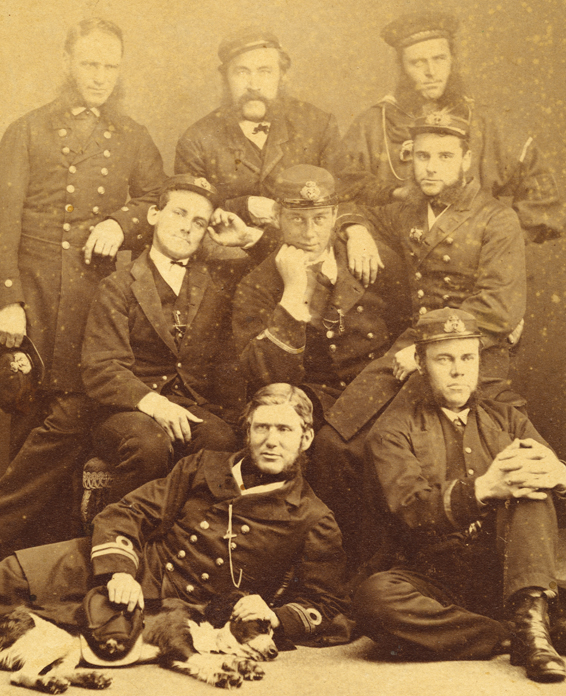

Nine members of The Queen’s Own Rifles of Toronto died on the battlefield. [Courtesy of The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada Regimental Museum]

“Just at the bend of the road to the north of the village, I met such a mixed and confused mass, as I have never seen elsewhere, before or since,” said Brewster.

“Soldiers and citizens, men, women and children on foot and in all varieties of vehicles, with horses, cattle, sheep and pigs, all mingled together, and all hurrying along the road south.

“I saw two soldiers without guns, running, and close behind them an officer with revolver in hand, crying halt, and firing in the air occasionally, but running as fast as he could. And close behind him more soldiers running.”

A company of the Queen’s Own Rifles had led the contingent out of the village. They were equipped with the most modern of weapons, the seven-shot Spencer repeating rifle. This American-made rifle had proven decisive for Union troops and cavalry in a number of recent battles south of the border. The York Rifles and the 13th Battalion (Hamilton) followed in the line of march. The Caledonia Rifles formed the rearguard.

They had marched only three kilometres when they encountered Fenian pickets at fences and hastily erected “rail barricades” in fields and near the crossroads. It was not ideal country for fighting, according to Denison, although the Fenians seemed to have no trouble.

“It should also be mentioned that these fields are much cut up with orchards, and that a large number of beautiful shade trees are scattered about,” said Denison. “These trees and the peculiar conformation of the ground renders it exceedingly difficult to get an extended view in any direction over the scene of the fight.”

Undeterred by the fleeing troops, Brewster continued to make his way forward until he happened upon the rearguard.

“Soon after I saw that some of our men had taken possession of the buildings on the corners at the first crossroad north of the village…and were gallantly trying to hold the enemy in check,” said Brewster. “And how I wished there were even a few veterans tried in battle among them, to hold them steady; but it was not long until I saw wavering among them and soon they broke and continued their retreat.”

The withdrawal was chaotic, even in Denison’s generous account, written through interviews with fellow soldiers and regimental battle diaries: “The two regiments, retiring along the same road, became mingled together—some few running hurriedly to the rear, others retiring more slowly, while a large body of red coats and green, fighting gallantly, slowly and sullenly retired, covering the retreat, and holding the Fenians at bay.”

Most of those forming the rearguard were officers, some of whom ended up wounded. Two of the units—the Highland Company and the University Rifles—had to cut diagonally across a field in front of the militants to reach the road and fall back with the main column.

The militants, according to Denison, lost an opportunity to deliver a significant blow—one that could have turned the retirement into a rout. “Had the Fenians advanced promptly, they would, in all probability, have cut off the retreat of both [companies],” said Denison. As it was, the University Rifles suffered horrible casualties from the withering fire as they moved across the field.

A local reserve force called Les Écharpes Rouges (the Red Sashes) repelled a Fenian raid at Frelighsburg, Que., on May 25, 1870, capturing a cannon in the process. [Wikimedia]

“Being now in the line of fire, I hastened to the left and made a circuit around the contending forces to the rear, and while in the fields, I heard shouting and firing but paid no attention, until I heard bullets whistling over my head, the other being ordinary noises of war.

”The Fenians had spotted him. “I was soon among them and a prisoner. ”What surprised him most was that the majority of the Irish militants wore no uniform, save one man who was dressed in the full regalia of a captain in the Union army. The man had not taken it off since the war.

“I told him it was time he did, as this was no place for it, and that I thought too highly of that uniform to see it worn in such a cause, as I had myself worn it for three years,” said Brewster.

The firing died down quickly and the Fenians advanced slowly through the village and posted their advance pickets on a hilltop facing west toward Port Colborne. The Canadians, however, were not coming back, at least not in the near future.

A home guard, of sorts, had been formed on the day before the battle as first reports of the Fenian landing arrived. The guard was separate from the Canadian militia forces and, according to Brewster’s account, the motley crew conducted mounted, armed patrols along the roads east and north of the village at night. With the army defeated, those additional volunteers also took flight.

It was an extraordinarily tense few hours. “[The Fenians] settled down for rest and food, in some cases cooking and eating their dinners in private houses, even setting the table in my own house,” said Brewster.

No doubt, there were fresh memories of how Union troops had laid waste to whole captured towns in the South, but Brewster seemed pleasantly surprised by the discipline of the militants who “took very little loot beside food and did practically no damage to private property.”

When the Fenian occupiers learned that Brewster was the local doctor, the grubby former Union captain ordered him back out to the battlefield where the victors were still locating the dead and tending the wounded.

“I scoured the fields, road and buildings, gathering in the wounded, all of whom I cared for,” said Brewster. He dutifully recorded their names, rank, company and regiment on a piece of scrap paper. It didn’t matter whether they were Canadian or Fenian. In the end, he had 26 names. Six of them—two Canadians and four militants—were mortally wounded. “One of the Canadians died from heat and exhaustion in my presence, being wounded, a student of the University of Toronto and a member of the University Rifles brought in from the field while still living.”

Five nearby houses were converted into makeshift hospitals under Brewster’s direction. One of them, the landmark “The Smuggler’s Home” tavern located within sight of the battlefield, filled up quickly. Beds and tables were appropriated. Unhinged doors were laid over sawhorses or smaller tables. Eventually makeshift mattresses were scattered about the floor.

“One of our wounded [Canadian] officers, thinking he must die, gave me his sword and belt, gold watch, rings…and exacted a promise from me that I should visit his wife, be the bearer of certain farewell messages, giving her all but the sword and belt, which I was to keep,” said Brewster. Overhearing the conversation, a covetous Fenian tried to grab the sword as a souvenir. With the help of a guard, posted to keep watch on the prisoners, Brewster managed to keep hold of the sabre for the duration of the occupation.

The wounded officer told Brewster how disaster had overtaken the young inexperienced Canadian troops. He listened at the man’s bedside with undisguised dismay. On coming across the Fenian pickets, the Queen’s Own advanced across an open field. They were nervous after the first shots were exchanged.

“I was told by our men that they were sanguine of success, until the fatal blunder that ordered them into squares to resist cavalry, which they obeyed,” said Brewster.

A period map details the last battle fought in Ontario against a foreign invasion. [Wikimedia]

“Instead of cavalry, they found a line of veteran infantry trained to service in many hard-fought battles in the American war facing them, who were quick to see and profit by the false move,” said Brewster. “They tried again to get into line, but being pressed, fell into disorder, then broke and began their retreat.”

The left and centre of the line collapsed, but Canadians on the right continued to press forward “and occupied a part of the enemies’ breastworks.” But soon they found themselves cut off and retreated “easterly until they reached the lake near Windmill Point.”

It was a fiasco. And sitting in the dank makeshift hospital among the wounded and dying, Brewster couldn’t help but be angry. In his mind, Booker bore responsibility.

“I could not but reflect upon the fitness for command of a man whose excited imagination could multiply two mounted men into a troop of cavalry,” he said. “I was assured by many of our men, officers as well as privates, that all was going well…until that stupid order to meet cavalry, which they saw did not exist….

I have not spoken with one of the participants since who did not believe that was the cause of the disaster.”

The sense of outrage grew only more intense as Brewster treated another young officer, Ensign Malcolm MacEachern of the Queen’s Own.

“Upon trying to reform his line after it was clear no cavalry was about to descend on them,” said Brewster, he stepped out in front of his men to rally them “when he fell, dangerously wounded by a ball in the back which, passing within an inch of his heart, came out in front.”

MacEachern died of his wounds. In all, nine Canadian soldiers died that day.

“I have often thought it would have been better had that bullet found a victim in the commander and that the history of the ‘Fenian Invasion’ would have had a very different ending,” said Brewster. Denison’s account was kinder to Booker, whose experience, but not his fitness, he questioned. He laid much of the blame on the inexperience of the troops, something Brewster acknowledged as he walked among the wreckage of the fight. He estimated that the rebels held a slight advantage in terms of numbers, but possessed leagues more experience and coolness under fire.

“A very large percentage of them were seasoned veterans used to war and battle; while ours were, to a man, raw recruits. Not one of them had ever before heard the whistle of hostile bullets or, as the phrase is, ‘smelled powder.’

“I have never seen the Fenian loss reported, but I found four of their dead, and learned from people living on those roads that at least six wagons carrying dead and wounded were seen going toward Fort Erie.”

Expecting to be overwhelmed by British reinforcements, the Fenians decided to fall back to Fort Erie, where they ran into another, smaller Canadian force which, travelling from Port Colborne via tugboat, had landed in the town.

Little is known about that engagement, which took place only hours after the fight at Limestone Ridge, although the odds favoured the Irish militants from the outset. There were approximately 70 Canadian militiamen facing roughly 700 Fenians.

The house-to-house fighting was savage and took place in close quarters with a number of soldiers suffering bayonet wounds. No clear-cut account of the action was written, despite subsequent inquiries. Coincidentally, both investigations were chaired by Denison.

The raiders attempted to slip back across the Niagara River into Buffalo, N.Y., but many were halted by a U.S. Navy gunboat, the USS Michigan, and arrested. Most were eventually released on the promise they would return home peacefully.

Not long after the Fenians were expelled, Brewster noted the return of the home-guard units. “They again patrolled the roads east with a good degree of efficiency, a fact brought home forcibly to myself, as they twice halted me on my rounds,” he said.

Eight militia officers who fought at Ridgeway. Post-battle inquiries blamed inexperienced troops, not the officers who led them. [John Dixon/LAC/e007152308]

The political fallout of the raid was stark. Less than a week later, on the Monday after the battle, Governor General Charles Stanley Monck delivered the first speech from the throne in the new Parliament Buildings. It made reference to the battle in Ridgeway and expressed sorrow at the casualties. The government of the day, according to records of the debates, faced heated finger-pointing over the preparedness of the militia.

The attorney general and minister in charge of the militia, John A. Macdonald—the future prime minister—ordered two military boards of inquiry to get to the bottom of why the Canadians had suffered such a humiliating defeat.

Some historians suggest the Fenian action cemented the necessity of Confederation in the minds of provinces that had only been lukewarm to the idea. A little more than a year later, a united Canada was born as a semi-independent dominion.

Returning home after discharging his duties, Brewster found that he had lost something of value in the ensuing confusion: his old uniform, which hung in his closet, had been stripped. “The gold lace and insignia of rank from my uniform, which I was keeping as a souvenir” were gone. Months after the raid, he took a personal pilgrimage to deliver the sword he had been entrusted back into the hands of the officer whose life he had saved.

When Brewster put his account in writing in 1911, the battle had largely faded in both the public consciousness and political memory. It was, even at that time, well on its way to becoming a footnote in history.

Which may not be all that surprising. There was good reason for the government of the day and the future prime minister to downplay the events. Acknowledging a defeat, particularly to the Irish, was not something Victorian British subjects and politicians were keen on.

Years afterward, however, Brewster said he witnessed visitors who would show up at Limestone Ridge to gawk and even rub their hands over the brick walls of the houses which had been pockmarked by bullets.

Advertisement