Jill Heinerth at Chukk Lagoon. The explorer and underwater photographer has made more than 7,800 dives, including over 20 on the wartime wrecks off Bell Island, N.L. [Courtesy Jill Heinerth/ INTOTHEPLANET.com]

She’s famous for her cave dives, including inside an Antarctic iceberg the size of Jamaica. But some of the most poignant adventures the Mississauga, Ont., native has undertaken may be to wartime wrecks off Newfoundland and in the faraway wonder once known as Truk Atoll.

In an interview with Legion Magazine, Heinerth described the unfailing anticipation—more than three decades on—of leaving her worldly cares behind as she descends into the “bracing cold” of Conception Bay and encounters the first telltale signs of a ship looming on the ocean bottom, 50 metres down.

“You descend the line, and you start to see the shadow first, and you know you’re approaching the wreck,” she said. “And then little things start to become focused, and your brain develops a picture of the ship’s orientation and what’s beneath.

“And when you reach the deck, I guess I feel reverence. I feel like a witness to history. I hear the voices from the people who would have been aboard. It’s different from caves in that most of the time we’re diving on the site of what was an incredible human tragedy and, yet, it has somehow been transformed by the ocean into something that is beautiful.”

Their route to the bottom was anything but beautiful.

“In caves, I always tell people that I am literally swimming through the veins of Mother Earth.”

In the fall of 1942, two U-boats—U-513 and U-518—sunk four ore carriers off Bell Island, Nfld., in separate attacks two months apart. Sixty-nine merchant crewmen were killed and an errant torpedo destroyed a loading dock.

The ships lie within a 5.5-kilometre radius at the anchorage, their holds still laden with iron ore from the Bell Island mines. The cargo is even spilling out of the gaping torpedo hole in PLM 27. Heinerth has dived the wrecks 20 or more times apiece.

“It seems so long ago but it is so prescient today,” says Heinerth, who was preparing to head back to dive Conception Bay yet again. “It’s pretty sobering.”

She grew up watching the Apollo moon landings and the underwater exploits of French explorer Jacques Cousteau. The ocean became her second home.

“My family jokes that because I was three weeks late being born, I just didn’t want to leave my ‘sweet mother’s ocean soul,’” she says. “But, yeah, it is very much a back-to-the-womb kind of experience for me.

“In caves, I always tell people that I am literally swimming through the veins of Mother Earth; I am inside the sustenance of the planet, in this lifeblood that serves humanity, wildlife, even all the industries that we need.”

She describes it as a “primal experience,” but adds that it is exploration and an insatiable curiosity that drive her more than anything—the opportunity to go places no one has ever seen before and may never see again.

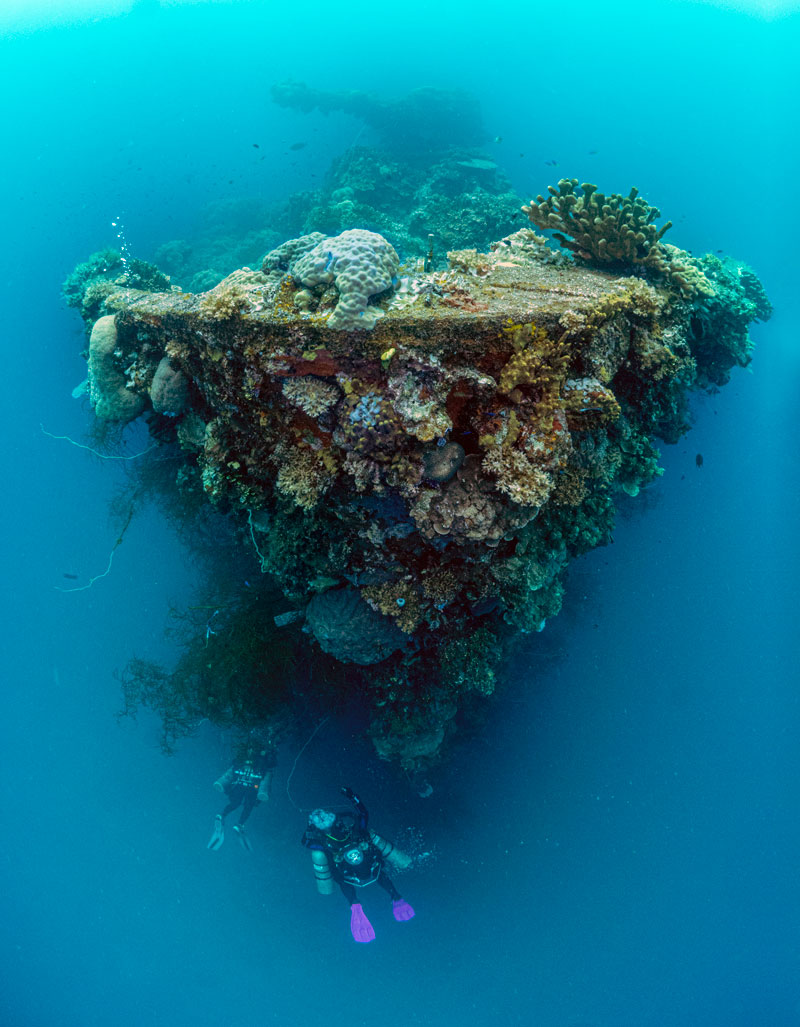

The anemone-encrusted bow of PLM 27 lies at the bottom of Conception Bay off Newfoundland’s northeast coast. Laden with iron ore from the Bell Island mines, the Free French ship was one of several sunk by U-boats in the fall of 1942.[Courtesy Jill Heinerth/ INTOTHEPLANET.com]

“The first time I saw the barrel of one of these defensive guns with anemones sprouting out of the end, I think that touched me more than anything.”

She’s lost more than 100 friends to diving accidents, many of them among the labyrinthian innards of wrecks, where hanging cables, sharp edges and darkness compounded by clouds of silt and rust particles pose immeasurable dangers.

She has witnessed evidence of humankind’s impact on the environment in even the world’s remotest places—pollution and climate change, particularly. Yet she remains hopeful, even optimistic, that the continuing resilience, abundance and beauty of the undersea world are positive signs of a better future.

Diving, she says, “gives me a chance to escape the noise of the world topside and focus my attention on something that unites us—our water planet—and hoping that we’ll all recognize how important it is to protect it for the future.”

Which is why she describes the blooming wrecks of Conception Bay as “prescient.”

A diver swims through a torpedo hole aboard PLM 27. Heinerth marvels at how the site of “incredible human tragedy” can be transformed by the ocean into something beautiful in less than a human lifetime.

[Courtesy Jill Heinerth/ INTOTHEPLANET.com]

“Beautiful, colourful life just grows all over them. The first time I saw the barrel of one of these defensive guns with anemones sprouting out of the end, I think that touched me more than anything. This used to spit salvos of ammunition and now it’s just growing this bouquet of anemones. It’s incredible.”

A world-class underwater photographer, her personal favourite is the Saganaga, aboard which 29 crew died on Sept. 5, 1942. The ship is still loaded with 8,300 tons of iron ore. It’s in shallower water and when the sun shines, the white anenomes “open up like flowers; sometimes you’ll go down and it’s just this puffy white mass.”

She’s explored the ships’ insides, found plates, cups, phonograph records and other personal items—and left them where they lay. Military divers recently removed most of the ordnance that had remained aboard the victim vessels for more than 75 years.

Heinerth has been inside the radio room aboard the 7,800-ton Rose Castle, its equipment still intact. She imagines the radioman sitting there at his Marconi set, transmitting a last message.

She has swum the Bell Island wrecks with a German dive buddy, less than a lifetime after our two countries were at war. In 2010, Marita Collings, the daughter of U-513 skipper Rolf Rüggeberg, visited Bell Island. She was welcomed with open arms and presented the local historical society with a collection of her father’s artifacts.

“If everybody could just see that things can change,” said Heinerth.

What they left behind is now dubbed “the world’s biggest ships’ graveyard.”

A diver hovers over Saganaga’s multi-tonne anchor, now lying on the ship’s aft section 25 metres down after it was propelled from the bow as the stricken vessel folded and broke in two.[Courtesy Jill Heinerth/ INTOTHEPLANET.com]

The site in the Caroline Islands, one of the archipelagos comprising the Federated States of Micronesia, was Japan’s main South Pacific base during the Second World War, manned by almost 28,000 men of the Imperial Japanese Navy.

Battleships, aircraft carriers, cruisers, destroyers, tankers, cargo ships, tugboats, gunboats, minesweepers, landing craft and submarines were anchored in the lagoon. Japan withdrew its larger warships before the Americans attacked early on the morning of Feb. 17, 1944.

The operation, known as Hailstone, lasted three days. U.S. carrier-based planes sank 12 Japanese warships and 32 merchant vessels. They also destroyed 275 aircraft, mainly on the ground.

Canadians were part of a force of British Pacific Fleet ships that staged a second attack, Operation Inmate, in June 1945. Japanese forces on Truk and other Pacific islands were starving by the time Tokyo surrendered in August 1945.

What they left behind is now dubbed “the world’s biggest ships’ graveyard.”

“The wrecks are extraordinary,” said Heinerth. “There are dozens of wrecks and they were all sunk simultaneously, basically, and they’ve all become incredible artificial reefs. The colour is unbelievable.

“They’re very, very intact, many of these wrecks, so we can easily penetrate some great distances inside of them.”

They are not as fragile as the Newfoundland wrecks, she notes. The lagoon itself provides some protection. Besides dissolving into the ocean, as all wrecks do, the hulks at the bottom of Conception Bay are fighting an annual war with ice—and losing.

A diver enters the hold of the Fujikawa Maru, an armed Japanese transport. The 6,938-ton ship was sunk in Chuuk Lagoon during a U.S. attack in February 1944.[Courtesy Jill Heinerth/ INTOTHEPLANET.com]

“More people have walked on the moon than have been to some of the places Jill Heinerth has gone right here on Earth.”

Heinerth wrote a bestseller, Into the Planet: My Life as a Cave Diver. She was inducted into the International Scuba Divers Hall of Fame in 2020 and was named the first Explorer-in-Residence of the Royal Canadian Geographical Society.

She was the inaugural recipient of the Sir Christopher Ondaatje Medal for Exploration and Canada’s Polar Medal.

“More people have walked on the moon than have been to some of the places Jill Heinerth has gone right here on Earth,” said explorer and filmmaker James Cameron.

For her part, Heinerth is always looking to that next discovery, that next time she suits up and the great unknown—the least-explored, least-understood part of our planet, the part that covers 71 per cent of it—awaits.

“As you’re getting ready to dive, you’re engaged and preparing your gear, but you’re also thinking about everything in your life,” she says. “It’s a noisy world, above the surface.

“But as soon as you take that giant stride into the water, the cold—the bracing cold—of the Newfoundland water immediately transports you to another place and you become incredibly focused only on what you’re doing in the moment.

“Certainly it’s very exciting—I feel a bit of a rush through my body as I’m doing that.”

Even after 35 years.

Divers explore the bow of the Fujikawa Maru in the South Pacific. More of Jill Heinerth’s wreck photographs can be seen in Canvet’s latest special edition, U-boats attack: The Battle of the St. Lawrence, now on newsstands across Canada.

[Courtesy Jill Heinerth/ INTOTHEPLANET.com]

For more of Jill Heinerth, visit her website at https://www.intotheplanet.com/. U-boats attack: The Battle of the St. Lawrence, the latest volume in Canvet Publications’ special edition series, Canada’s Ultimate Story, is now available on newsstands or go to https://canadasultimatestory.com/uboats-attack-battle-of-the-stlawrence and order for home delivery.

Advertisement