Mercifully, the First World War was the last major confrontation in which horses played a major role.

British cavalry were among the first units to see action in WW I, but they didn’t last. The war’s most impactful weapon—the machine gun—along with the mud and barbed wire of trench warfare would ultimately spell the end for equine-borne military.

One of the last successful cavalry charges on the Western Front took place at the Somme—on July 14, 1916, when the 20th Deccan Horse, an Indian cavalry unit, attacked a German strongpoint at High Wood. Armed with lances and despite an uphill climb, enough horsemen reached the woods to force some Germans to surrender.

The cost, however, was high: 102 of the attackers were killed, along with 130 horses. Two months later, the tank debuted alongside Canadian and other Allied troops at the Battle of Courcelette. Cavalry encounters continued, on the Eastern Front especially, for some time yet, but war would never be the same.

Mounted units such as Lord Strathcona’s Horse (Royal Canadians) and the Fort Garry Horse, formerly the 34th Regiment of Cavalry, would gradually transition to mechanized armour. The war horse was relegated to the drudgery and indignity of heavy work, hauling supply wagons, ambulances, lumber, artillery pieces and more.

The Canadian Expeditionary Force used 24,134 horses and mules over the course of the war in France and Belgium.

The British Army alone employed 1.2 million horses. It had just 25,000 at its disposal in 1914; it bought another 115,000 under the compulsory Horse Mobilisation Scheme, depicted early in the movie War Horse.

“Goodbye, Old Man” by Italian master illustrator Fortunino Matania depicts a soldier bidding farewell to his mortally wounded horse. It was commissioned by the Blue Cross Fund, a charity established for the benefit of horses wounded in war and used by a number of animal relief agencies. [Fortunino Matania/W.F. Powers Litho Co./CWM/19890094-003]

From 1914 on, 500 to 1,000 horses were shipped to Europe each day; 130,000 of them came from Canada. The British Army spent the equivalent of $5 billion in today’s currency on buying, training and delivering horses and mules.

Whole industries were dedicated to feeding, doctoring and maintaining them. By 1917, Britain had more than 368,000 horses employed on the Western Front—still not enough, apparently, as some troops were told that the loss of a horse was of greater tactical concern than that of a soldier.

Nevertheless, the troops loved them and horses often boosted front–line morale. But their waste and their carcasses also contributed to poor sanitation and the spread of disease.

The animals suffered terribly. They were mutilated by artillery fire, plagued by skin disorders, and blinded and burned by poison gas. Procuring fodder was a major challenge and Germany, enduring blockade shortages, lost many horses to starvation. Even the U.S. Army was in dire need of horses just months after joining the fight.

The losses were staggering. Some 7,000 horses were killed on a single day by long-range shelling during the Battle of Verdun in 1916.

By war’s end, 2.5 million had been treated by war veterinarians and eight million had died, three-quarters of them from extreme conditions. The heavy-hauling Clydesdales suffered the most. It took six to 12 just to pull a single field gun through the notorious mud.

On June 8, 2018, the War Horse Memorial was unveiled in Ascot, England. It is the first national memorial dedicated to the millions of United Kingdom, Commonwealth and Allied horses, mules and donkeys lost in the Great War.

“It pays tribute to the nobility, courage, unyielding loyalty and immeasurable contribution these animals played in giving us the freedom of democracy we all enjoy today, and signifies the last time the horse would be used on a mass scale in modern warfare,” says the memorial website.

The Beaverbrook Collection of War Art at the Canadian War Museum is replete with depictions of horses at war. Here are some from the First World War:

On Sept. 1, 1914, during the withdrawal of British and French forces following the Battle of Mons in Belgium, a German cavalry division attacked a British cavalry brigade about half its size at the French village of Néry. Within minutes, the British guns were all but wiped out. But a single 13-pounder of ‘L’ Battery, Royal Horse Artillery, kept up a steady fire for two-and-a-half hours against a full battery of German guns. British reinforcements finally arrived, counterattacked and forced a German retreat. Three gunners—Captain Edward Bradbury, Battery Sergeant-Major George Dorrell and Sergeant David Nelson—were awarded the Victoria Cross. Mons remained in German hands until it was liberated by Canadian troops on the last morning of the war, Nov. 11, 1918. [Fortunino Matania/Henry Graves and Co. Ltd./CWM/20060056-001]

Painted by Alfred Munnings between 1918 and 1919, this study for a never-completed mural depicts soldiers and horses transporting wounded, led by a white-veiled nurse in a blue uniform. Munnings was attached to the Canadian Cavalry Brigade for part of his service and became celebrated for his horse paintings. [Alfred James Munnings/CWM/19710261-0482]

This unfinished piece depicts a Canadian trooper of Lord Strathcona’s Horse (Royal Canadians) and his trusty steed. The regiment fought as infantry and as mounted cavalry during the 1914-1918 war. By the Second World War, it had become a full-blown armoured regiment based in Edmonton. It deployed the first Canadian armoured troops to Afghanistan. [Alfred James Munnings/CWM/19710261-0460]

Nearly three-quarters of the Canadian cavalry involved in this attack against German machine-gun positions at Moreuil Wood in France on March 30, 1918, were killed or wounded—including Lieutenant Gordon M. Flowerdew of the Lord Strathcona’s Horse (Royal Canadians), who was awarded the Victoria Cross for leading the charge. The cavalry, however, remained behind the lines for much of the war, unable to break the trench deadlock and of little use at the front. During the German offensives of March and April 1918, however, the cavalry played an essential role in the open warfare that temporarily confronted retreating British forces. [Alfred James Munnings/CWM/19710261-0443]

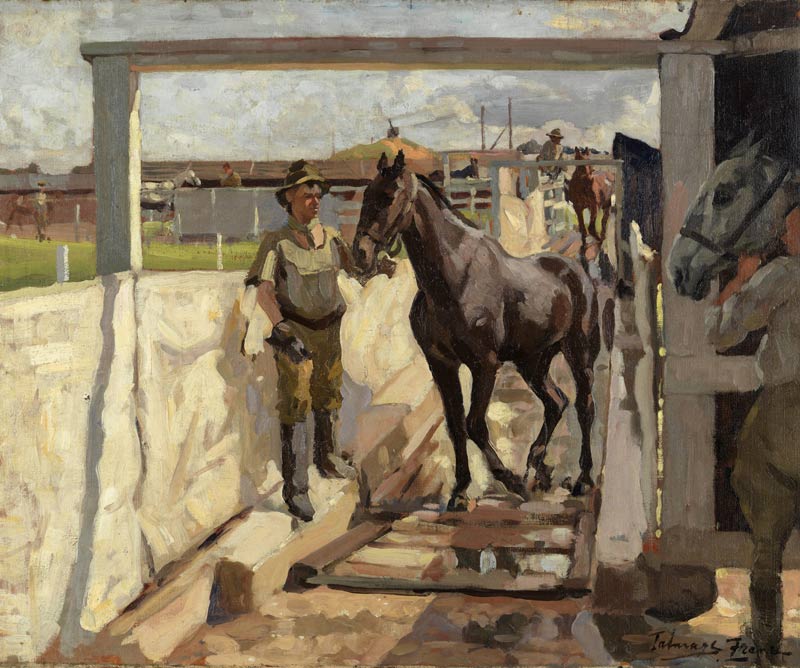

“A Mobile Veterinary Unit in France” shows the Canadian Army Veterinary Corps near the front. Formed in 1910 with seven sections from Calgary to Halifax, 73 veterinary officers and 780 enlisted of the Canadian Army Veterinary Corps treated more than 24,000 horses overseas. One of its veterinarians, Captain Harry Colebourn, born in London and emigrated to Winnipeg, is best known for donating a bear cub to the London Zoo. He named it “Winnie” for his adopted home after buying it in White River, Ont., on his way to the Canadian Forces base at Valcartier, Que. The bear would become the inspiration for A.A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh. The regiment received its ‘Royal’ designation eight days before the war ended. Responsible for returning 80 per cent of the animals under its care to active duty, the vet corps was ultimately disbanded in 1940 in order to save $10,334. [Algernon Mayow Talmage/CWM/19710261-0596]

Ready to attack, Canadian cavalry assemble in a wooded area. In November 1916, Canadian-born Max Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook, founded the Canadian War Memorials Fund and eventually commissioned Bastien and 115 other artists to paint some 900 scenes of Canada at war. The collection was supplemented with war art from the Second World War and the postwar period, right up to Canada’s war in Afghanistan. The Beaverbrook Foundation chose the Canadian War Museum to be stewards of this extraordinary war art collection and continues to be one of the museum’s most generous donors. [Alfred Theodore Joseph Bastien/CWM/19710261-0095]

Titled “Horses and Chargers of Various Units,” this painting depicts horses apparently taking a water break. A soldier on the left is filling a bucket from a stream. More troopers approach carrying buckets while others keep the horses in check. Bastien and Munnings’ classical style was well suited to First World War art and tended to convey mood more than the illustrators’ medium. [Alfred James Munnings/CWM/19710261-0448]

“The Sulphur Dip for Mange” depicts veterinarians of the Canadian Army Veterinary Corps treating horses for mange, a skin disease caused by parasitic mites. The veterinary corps set sail for England with Canada’s first contingent in October 1914. Most of English artist Algernon Talmage’s paintings were based on time spent near Quéant, on the Hindenburg Line in France, in 1918. [Algermon Mayow Talmage/CWM/19710261-0692]

The Canadian Forestry Corps was created on Nov. 14, 1916—its circular badge topped by a beaver superimposed on a pair of crossed axes, with “Canadian Forestry Corps” around the edge. At the centre of the circle is a maple leaf with the Imperial State Crown. Nicknamed the “Sawdust Fusiliers,” they were responsible for harvesting the huge amounts of wood needed on the Western Front—duckboards, shoring timbers, crates. The British government concluded that there was nobody more experienced or qualified in the British Empire to harvest timber than the Canadians. At first the idea was to cut trees from Canadian forests and bring them overseas, but space was at a premium aboard merchant ships so they brought the lumbermen to the forests of Europe instead and, along with transfers from some frontline units, they harvested trees in England, Scotland and France. Horses were integral to their work, and the corps invited Munnings to tour their work camps, where he produced drawings, watercolours and paintings. [Alfred James Munnings/CWM/19710261-0461]

“Fort Garrys on the March” depicts the Fort Garry Horse on a road somewhere on the Western Front. The army reserve unit arrived in France in February 1916. It fought in France and Flanders as part of the Canadian Cavalry Brigade until the war’s end. The regiment’s Lieutenant Henry M. (Harcus) Strachan was awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions at the Battle of Cambrai on Nov. 20, 1917. A Scottish-born homesteader from near Wainwright, Alta., Strachan was 33 years old when he assumed command of ‘B’ Squadron after his commanding officer was killed by machine-gun fire. With Strachan leading the way and unaware that large-scale cavalry action had been abandoned, the squadron cut its way through a line of infantry on a heavily camouflaged road at the German-held village of Masnières, France, only to be confronted by a four-gunned German field battery. They charged and rode down or sabred the gunners. More German infantry fired on them and again Strachan led a charge. They broke through, taking fire and suffering casualties as they rode. With fewer than 50 men and only five unwounded horses, they sheltered in a sunken road outside the town. Strachan realized there was to be no support, so he had the horses cut loose and he led the unit in a fighting withdrawal, scattering four groups of German troops as they went. He brought all his unwounded men in, along with 15 prisoners. King George V awarded the newly minted Captain Strachan the VC on Jan. 6, 1918. [Alfred James Munnings/CWM/19710261-0457]

Advertisement