HMCS Guysborough was a Bangor-class minesweeper. [Wikipedia]

Just after 7:30 p.m. on St. Patrick’s Day in 1945, survivors of the minesweeper HMCS Guysborough were in frigid Atlantic waters awaiting rescue. About half of them wouldn’t make it.

Guysborough was about 300 kilometres off the coast of France in the Bay of Biscay en route from Lunenburg, N.S., to England when it was hit in the stern by an acoustic torpedo from U-868 just before 7 p.m. on March 17.

The ship was disabled but did not sink. The crew gathered on the main deck, waiting for a tow. The Germans fired again. The explosion killed two crew, and the ship listed to port.

Remaining crew “ran uphill and went over the rail on the starboard side,” recalled John Gleason, who shared his story with Legion Magazine in December 2013.

“Nearly half of us ended up around one Carley float.”

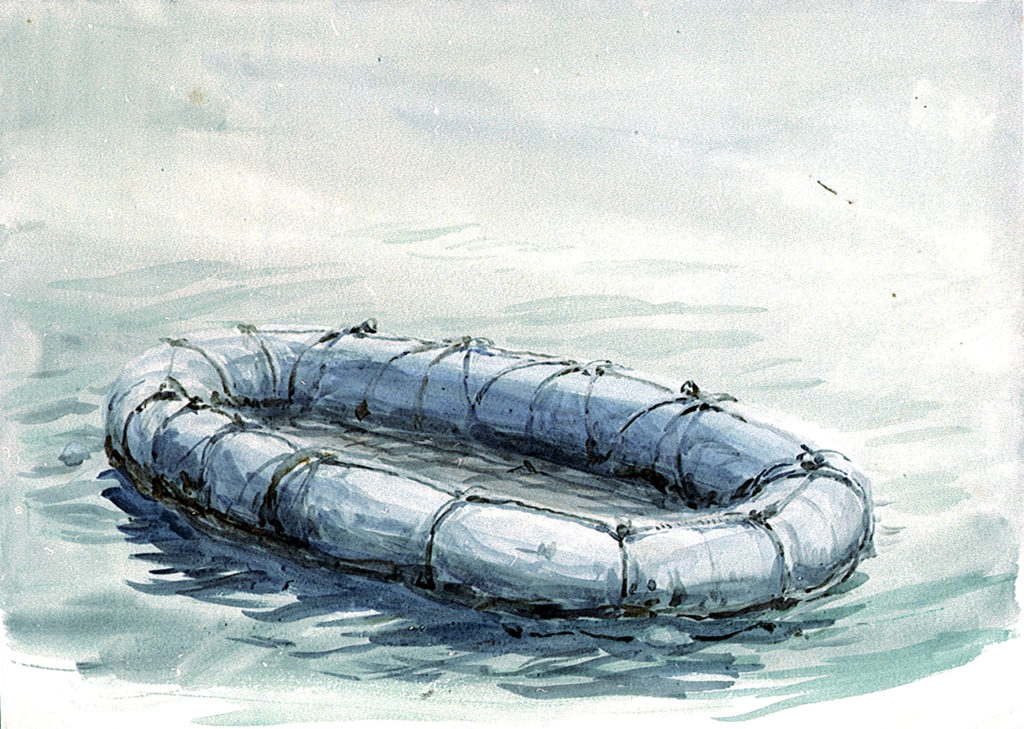

The ship’s motor cutter and whaler were unusable, forcing survivors to use life rafts called Carley floats.

“A Carley float is like an oblong doughnut with a slat bottom attached by ropes so that either side up works fine in the water,” Gleason said. The floats worked like a giant life preserver, with survivors clinging inside the ring, their lower bodies in the water. “Most warships had them and one big advantage was they could be cut loose quickly, thus providing something for the men to get into or cling to.

A Carley float is designed to carry 12 people. [Wikimedia]

“Nearly half of us ended up around one Carley float.” The other 48 survivors lashed four floats together. Darkness was falling and “we had drifted so far apart in the swells that we were unaware of it and that was unfortunate.

“I was glad the sub did not surface and shoot us in the water. But I resented the fact that they did not pick us up. And why two torpedoes? We were obviously crippled by the first, unable to move.”

Several ships received Guysborough’s distress signal, but it took 19 hours for rescuers to arrive. By then, 49 survivors had died of exposure.

Gleason spent hours in the water. “I was one of 42 crew members swarming around one Carley float designed to carry 12. Nineteen hours later, six of us were alive.

“I remember the total blackness of the night. I remember the eerie silence, only the gentle slushing of the sea around us, no one uttering a sound. I remember the hopeless feeling of isolation and the awareness that I would probably die soon. That I would never marry. Never have children.”

As the hours passed, the cold began claiming sailors. “They just drifted away, dead or no longer able to hang on…. The more men the sea claimed, the closer those left got to the float. The float was escape from the icy water, blessed rest for the arms, a chance to survive. I remember thinking that I was finally there. I could reach up and grab the ropes of the yellow raft!

“It was my turn to climb up…. I remember reaching out to the coxswain for help. He grabbed my hand and pulled, then said, ‘I don’t think I can do it, John.’

“Throughout our ordeal, the ’swain worked to keep our spirits up. In the beginning, he exhorted us to paddle on this side and kick on the other side and he would take us into Portsmouth. He was senior officer of our situation…and we respected his experience as a seaman.

“As reality set in, I began to feel that he was a bit too cheerful for the occasion, and this latest declaration did not modify my opinion. I tightened my grip like my life depended on it, which it probably did. ‘Sure, you can,’ I muttered. ‘Sure, you can.’ Somehow he managed to pull me in. ‘Welcome aboard,’ he said.

“I was among the last two or three to make it onto the Carley float. It was morning by then. There were 10 or 12 of us left [36 had died]. Those who drifted away during the night would have little chance of being spotted. I don’t think any were picked up alive.

“Sleep was equated with death on the float.… Most of us had been up for about 30 hours.” They sang songs to keep awake.

“Sometimes, I found it difficult to keep up with the words, and that was scary, so I’d jump ahead a line or so to keep up with the others. I was getting some funny looks, like maybe the choir would do better if you retired. I never really got into sync with the others, nor was I aware that this was just a precursor of a deadlier test yet to come.

“I remember a conversation with…a young telegrapher from my mess. He was sitting second over on my left, and he had reached over to get my attention. ‘You haven’t met my old man, have you, John? How about coming over Saturday, stay for dinner? OK? My sister Marge is home. She’s nice. You’ll like her.’

“Bob nodded off after some more about his dad. He was dead in 15 minutes and was slipped over the side. The ’swain had developed the habit of saying a few last words as the boys slipped away. This, at least, lent a semblance of respect—of order—to the ugly, heartbreaking stuff going on.

“There was no book! I was slipping away to la-la land.”

“We were all pretty tired by then.… I had nearly nodded off. The ’swain had reached across and slapped my face.

“A great idea had popped into my head. ‘I’ll show him.’ I placed both hands on my lap, palms up and then dropped my head down. I smiled to myself as I waited for the slap to come. ‘He will feel like such a fool. When he slaps me, I’ll say ‘why did you do that, I wasn’t falling asleep…I was just reading this book.’

“But before the slap came, a bolt of lightning hit my frozen brain. I looked at my hands, still grey and corrugated from hours in icy saltwater. There was no book! There was no book! I was slipping away to la-la land.

“A pint of adrenaline flooded through me and I was wide, wide awake, and stayed that way until we were picked up. There were six of us left when we were picked up around mid-afternoon.

“I was the only one able to scramble up the rope net instead of being hoisted up to the deck of the destroyer. Nor did I rest after rescue. I remember exploring the ship, and it was certainly a big sucker. Maybe I didn’t sleep for a week. I don’t remember. But I came back from the brink. I survived!”

Years later, Gleason came across news of the sub that sank Guysborough.

“It had one ‘success’—our ship—before being sunk by depth charges on April 10, 1945. The U-boat’s entire crew was lost. The war in Europe ended 28 days after the U-boat was sunk. Fifty-one dead from our ship, 51 dead on the sub: man for man.

“I started to cry at my desk. I was alone in the house and I just sat and sobbed. One hundred and two young men dead. Why?”

___

An exclusive audio version of John Gleason’s story “Adrift with Death” can be found at: legionmagazine.com/en/2013/12/adrift-with-death

Advertisement