U-boat Captain Otto Kretschmer (above, at right) is congratulated by a senior German officer for his success in sinking Allied ships. [VCG Wilson/Bettmann Archive/Getty Images/615218184]

In the spring and summer of 1943, while an officer with the Royal Canadian Air Force was overseeing the secret excavation of tunnels for a mass escape from a Nazi prisoner-of-war camp—the subject of the movie The Great Escape—a German naval officer was doing the same thing for a mass escape from a Canadian PoW camp 6,500 kilometres to the west across the Atlantic Ocean.

To make it to freedom from Stalag Luft III, 76 Allied airmen had to avoid the attention of guards in this tower, which they called a goon box. [Alamy/336270374]

But the efforts of Otto Kretschmer, a U-boat ace known as the Tonnage King, were somewhat less successful than those of Flight Lieutenant Wallace Floody of Chatham, Ont., immortalized in the movie as the Tunnel King.

Kretschmer joined the German navy in 1934, but two years later transferred to the U-boat force. He had commanded a submarine for two years before the Second World War was declared, and he sank a Danish ship and a British destroyer shortly after the war began.

In April 1940, he took command of U-99 and specialized in nighttime surface attacks, slicing diagonally through convoys to target individual ships. He prized precision. His motto—One torpedo, one ship—was in defiance of Kreigsmarine directives to fire salvoes to ensure sinking.

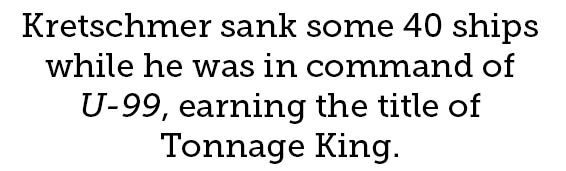

Kretschmer sank some 40 ships while he was in command of U-99, earning the title of Tonnage King by sending more than 270,000 tonnes of shipping to the bottom in his 18-month wartime career.

On March 16, 1941, on its eighth patrol, U-99 sank five ships in one hour. Out of torpedoes, his boat illuminated by burning ships, Kretschmer felt (as quoted in his Daily Telegraph obituary) “as exposed as a man sunbathing on a beach.”

He crash-dived, but the sub had already been spotted by the convoy escort and was attacked by HMS Walker. Six depth charges plunged U-99 to below crushing depth, followed by an abrupt rise to the surface. The steering gear was damaged and the fuel tanks had been smashed. He sent a signal to Germany: “Depth charges—captured—Heil Hitler—Kretschmer.”

He ordered U-99 scuttled to avert boarding by the Allies, then ordered his crew into lifeboats and flashed a message to the British ship: “Captain to Captain. Please save my men drifting in your direction. I am sinking.” Only three men were lost as the sub was scuttled; 40 were saved.

The loss of U-99 “is a serious blow to German morale and propaganda,” said the British interrogation report, especially since another U-boat ace was captured the same night. It was “an important victory” during the opening days of the Battle of the Atlantic.

Kretschmer and his crew were transferred to London, where Royal Navy interrogators found he was “less extremely Nazi than had been assumed,” and although 29, he looked more like a student than a U-boat captain.

The crew “had an exaggerated idea of their importance and dignity; these inflated opinions were no doubt due to the extraordinary degree of public adulation to which they had become accustomed.”

The crew’s contentment was a surprise. “For the first time in this war, no criticism of their officers was noted; on the contrary, a marked degree of loyalty and admiration for their Captain was expressed by the men.”

Kretschmer was a celebrated national hero. Adolph Hitler himself had decorated him with the Knight’s Cross with Swords and Oak Leaves. The crew received champagne treatment on shore leave.

The first lieutenant told interrogators that of the 14 torpedoes recently fired by U-99, 12 had hit their targets, one missed and one was a dud. “This statement is thought to be inaccurate,” said the intelligence report, though “the crew considered this a unique achievement.” It was the first the British had heard of ‘One torpedo, one ship.’”

As the German U-boat captain was being interrogated and sent off to PoW camp, first in England, then Camp 30 near Bowmanville, Ont., Flight Lieutenant Clarke Wallace Chant Floody was training to be a Spitfire pilot with No. 401 Squadron, RCAF in England.

At 18 years of age and looking for work during the depths of the Depression in 1936, Floody hired on as a mucker, shovelling rock and mud into carts at a mine in Northern Ontario. Later, after a brief stint as a ranch hand in Alberta, he married and settled in Ontario, intending on mine work.

In 1940, he enlisted in the RCAF and became a fighter pilot. On his first combat mission over France on Oct. 27, 1941, the controls of his Spitfire were wrecked in an attack by Messerschmitts. Floody bailed out and was immediately captured, becoming a PoW six months after Kretschmer. He was 23.

Floody was sent to Stalag Luft I, near Barth, Germany, located in a lagoon off the Baltic Sea. He put his mining experience to work immediately and was involved in many escape attempts. Escape, he said later, “wasn’t just your duty; you did your very best to get out.”

In 1942, he was sent to a more secure camp about 400 kilometres farther inland, in what is now Zagan, Poland: Stalag Luft III, which featured barbed wire, machine-gun towers, roving patrols, ferrets and guards expressly tasked to look for signs of escape. The huts were on pillars, located a long distance from the perimeter fence, which was cleared of nearby trees. Its sandy soil was not conducive to tunneling, but listening devices were employed to detect sounds of digging, just in case. The Germans considered it escape proof.

Floody was among those who proved them wrong. He was immediately recruited by the committee planning a mass escape of 250 Allied PoWs. It was hoped that some would make it back to England, but it was expected that most would spread out from the camp, causing the Germans to divert manpower and resources for their recapture.

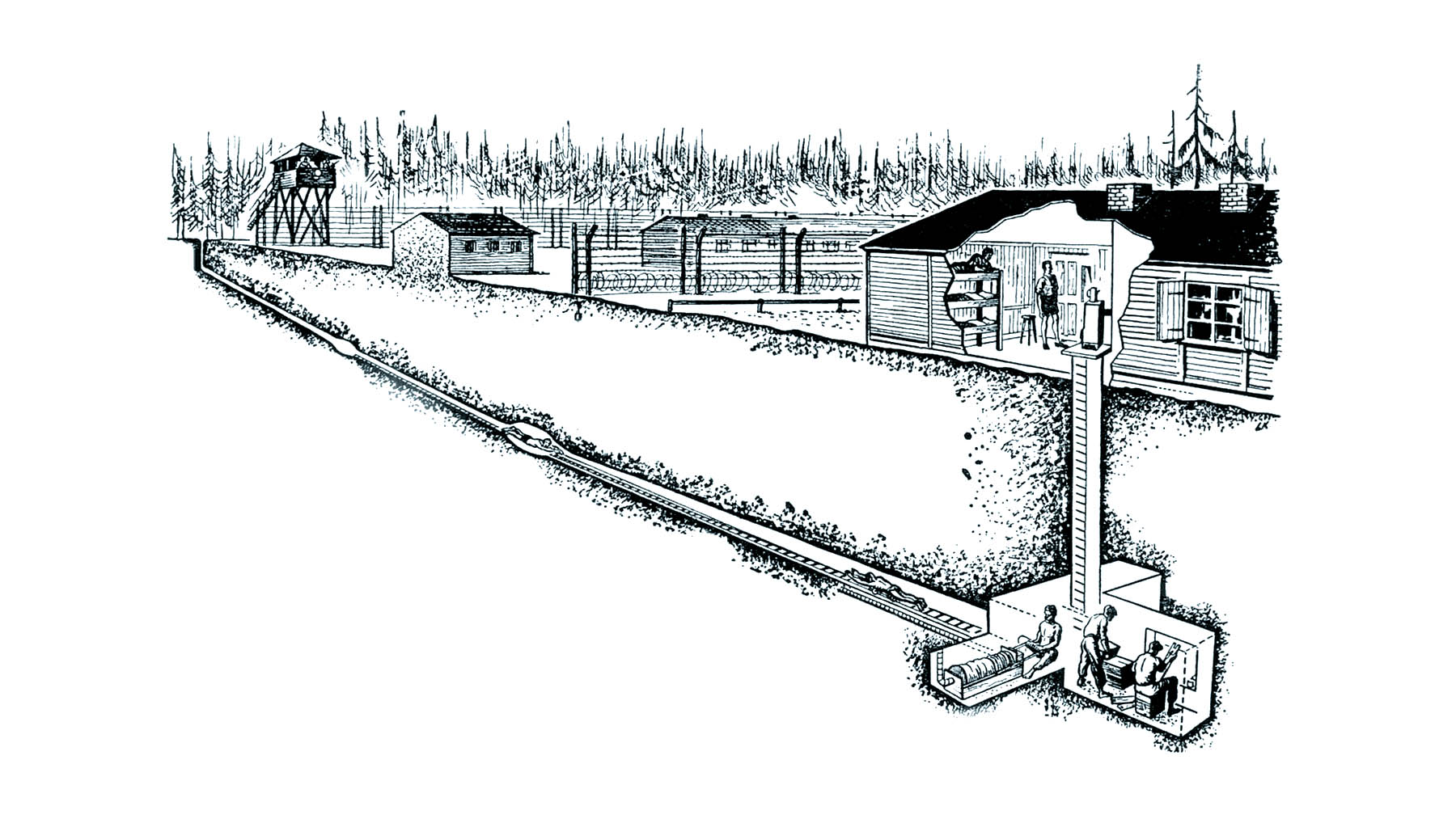

The plan was to excavate three 100-metre tunnels, nine metres below ground, out of range of German listening devices. Floody designed the lighting, ventilation and electrical systems, and was so vital to operations that he was forbidden to join other escape attempts. He was needed for the tunnels, named Tom, Dick and Harry.

“God, I am sick of them,” he complained. “I seem to spend my life down a stinking hole in the ground,” the Daily Telegraph in London reported in his obituary years later.

The tunnels, shored up with wooden slats from bunks and little more than a half metre wide, were claustrophobic to the six-foot-three Floody, who nevertheless took his turns digging. He was buried twice in tunnel collapses.

Prisoners scavenged (and pilfered) what they could, fashioned powdered milk cans into digging tools and lights and improvised a ventilation system from scraps. Teams made forged identity and travel documents and clothing so escapees could pass as civilians. For years, Floody kept the heel of an old boot, carved by razor blade to duplicate a Nazi rubber stamp. They bribed and cajoled friendly guards for train schedules, batteries and clothing, appropriated blankets, bedding, bunks, tables and chairs.

Every metre of tunnel produced 1.3 tonnes of dirt that had to be hidden. They mixed it with soil in the gardens, stuffed it in barracks attics and in one of the unused tunnels. With more than 11,000 PoWs crammed into barracks spread across 24 hectares, and prisoners assigned to distract prying guards, they pulled it off.

The ingenious escape tunnel was designed by RCAF officer Wally Floody. [Flight Lieutenant Ley Kenyon/Royal Air Force Museum]

The German PoWs in Canada were interned in a former boys’ training school. Even with an expansion, it housed less than a tenth of Stalag Luft III’s population. And the high rank and profile of many internees, including three generals, invited scrutiny.

Against this background, Kretschmer planned his escape. He not only had to figure out how to escape the camp, but how to avoid capture for days or weeks while travelling to the Atlantic coast, and how to cross the ocean back to Germany.

He turned to German U-boat command for help. A fellow PoW was married to the secretary of Admiral Karl Dönitz, who created and headed the U-boat fleet and became commander-in-chief of the German navy. Kretschmer used the spouses as a conduit for coded messages in which the first letter of each word represented dashes and dots of Morse code.

RCAF officer Wally Floody, (front row, second from right). To his right is Flying Officer Henry Birland, who was executed by the Gestapo after the escape.[Ted Barris/IWM/205314318/Royal Air Force Museum]

Kretschmer suggested an escape route and chose Pointe Maissonette on Chaleur Bay in New Brunswick for the rescue by U-boat, ideally on Sept. 27 or 28. Operation Kiebitz—which was to spring four valued Kriegsmarine (navy) personnel—was born.

It was soon followed by a Canadian counterplot, Operation Pointe Maissonnette. Canadian naval intelligence had cracked the code used to communicate between Germany and Canada and was co-ordinating with the RCMP to foil the mass escape.

Parcels were searched more carefully. The RCMP crime detection laboratory in Regina found concealed escape materials in the binding of a novel in a Red Cross parcel—a marine map of the east coast, forged identification and currency. The map revealed the pickup point. Now plans expanded to include the capture of a U-boat, which would be an enormous coup.

The book could not be restored to its original condition, so to avoid revealing their discovery, RCMP intelligence officers carefully dismantled it, photographing each step, then created a duplicate cover and binding, concealed the secret contents in the binding, and sent it on to Camp 30.

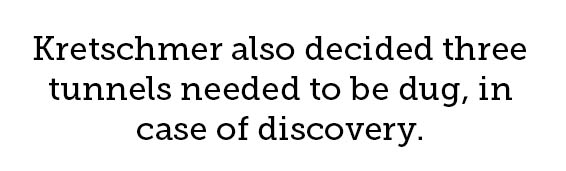

The escape mirrored, on a smaller scale, what was going on in Stalag Luft III. Kretschmer also decided three tunnels needed to be dug, in case of discovery. More than 150 prisoners worked on the excavations, one of which was 90 metres long. There were also teams preparing false ID papers and collecting and making civilian clothing. They also received helpful items through Red Cross parcels, such as Canadian money hidden in false bottoms of canned goods.

But Kretschmer’s crew lacked Wally Floody. Their tunnels were less than five metres down, within range of listening devices, which the RCMP used to track progress of escape preparations. The first tunnel collapsed from water seepage. The Germans hid the dirt from their tunnels in barracks ceilings, one of which caved in a week before the escape date, sparking a search of the camp.

Then a prisoner walking above a tunnel caused a cave-in too obvious to be ignored. The would-be escapees were arrested. Operation Kiebitz was kaput.

A German prisoner of war crossed hundreds of kilometres from Bowmanville, Ont., to rendezvous with a U-boat on New Brunswick’s coast.

But the commander of U-536, the sub on its way to pick up the escapees, knew nothing of this. A trap was being prepared for Kapitänleutnant Rolf Schauenburg

(see sidebar below).

Operation Pointe Maissonette was originally planned as an elaborate ruse. Prisoners would escape and be recaptured immediately. The media would be informed of a mass escape and false news planted of fictitious recaptures, including names of fictional escapees and minus names of those to be picked up. The U-boat commander would think the operation was proceeding as planned. But when the U-boat arrived at the rendezvous, it would be met by a German-speaking “officer” heading a boarding party that would take control of the boat.

That plan was nixed by the British. The new plan called for a naval dragnet to corral and sink the U-boat.

Crowded Stalag Luft III in Poland held Allied airmen captured by Germany. [Ted Barris]

Internment Camp 30 in Bowmanville held German prisoners captured by the Allies. [Ted Barris/IWM/HU21013]

Original plans for the recapture of PoWs remained in place, and even though Kretschmer’s escape was foiled, U-boat captain Wolfgang Heyda did break out and make his way to Pointe Maissonette (see sidebar on page 36).

U-536 entered Chaleur Bay on schedule and began a routine of surfacing for two hours a night for two weeks, awaiting escapees’ flash signals from shore. Lurking behind a nearby island were a destroyer, three corvettes and five minesweepers.

In the lead was HMCS Rimouski, outfitted with diffuse lighting camouflage, which made the ship virtually invisible at night. Rimouski was to enter the bay under camouflage and capture the submarine.

Schauenburg was a seasoned captain who had been aboard the battleship Admiral Graf Spee, which was scuttled following the first naval battle of the war. He had been taken prisoner, escaped twice, recaptured, then released after diplomatic negotiations. He joined the U-boat service after returning home.

The former PoW had good gut instincts and was already suspicious when he arrived in Chaleur Bay. His crew had spotted some of the warships earlier and the bay was unusually empty of shipping. On Sept. 27, signal lights flashed from shore, but were not as expected. An attempt was then made to contact U-536 by radio (by an English officer who spoke German). An alarmed Schauenburg moved away from shore and submerged.

Heyda, meanwhile, had just been captured about a kilometre from the rendezvous site. While he was being questioned, depth charges were heard—the navy dragnet was hunting down the U-boat.

But Schauenburg evaded the pursuers, staying submerged in very shallow waters and slowly making his escape. On Oct. 5, he alerted the German admiralty that their plan had failed. U-536 was sunk six weeks later by the British frigate Nene and Canadian corvette Snowberry while attacking a convoy northeast of the Azores, west of Portugal. Ironically, Schauenburg ended the war as he started it: a PoW, this time in a camp in Canada.

On the set of the movie The Great Escape, Wally Floody (above, at centre) confers with actors James Coburn (left) and Charles Bronson, who portrayed the pilot, but with Polish nationality. [LAC/4084411]

In the spring of 1944, the Allied officers’ great escape was a success. On March 24, the first Allied PoW emerged from the Stalag Luft III tunnel to discover he had not reached the nearby forest. He and other escapees had to cross open ground to reach cover, timing their sprint between searchlights and patrols.

Vital time was also lost during a power outage and for repair work. Only 76 men, nine of them Canadian, made it outside the wire before the escape was discovered; 73 were recaptured. Floody was not among them.

Three weeks before the escape date, guards became suspicious and transferred 20 PoWs, including Floody, to another camp. It may have saved his life.

Hitler ordered the execution of 50 escapees, including six Canadians, even though the Geneva Conventions held that attempted escapers could be given disciplinary punishment not to exceed a month’s imprisonment (and more usually 10 days). The Germans were warning the Allies that escape was no game.

But to prisoners on both sides of the ocean, it remained a duty. Floody was made a member of the Order of the British Empire for pursuing his.

“Flight Lieutenant Floody was largely responsible for the construction of the tunnel through which 76 officers escaped from Stalag Luft III,” reads the citation. “Throughout his imprisonment, he showed outstanding determination to continue with this work. Time and time again, projects were started and discovered by the Germans but, despite all dangers and difficulties, [he] persisted, showing a marked degree of courage and devotion to duty.”

Floody and Kretschmer both had successful postwar lives. The Canadian was a businessman and co-founder of the RCAF Prisoners of War Association. Kretschmer returned to the navy, rising to the rank of admiral. He became a NATO staff officer in 1962 and rose to chief-of-staff of the Baltic command.

Savvy Schauenburg

The U-boat captain sent to pick up German escapees from the Canadian prisoner of war camp in Bowmanville, Ont., had started the war as a PoW and was doomed to end it as one too.

Kapitänlutnänt Rolf Schauenburg, whose career started in 1934, was already an experienced sailor when he took part in the first naval battle of the Second World War as a flak artillery officer aboard the Admiral Graf Spee, which had sunk at least eight merchant ships before engaging with British ships at the Battle of River Plate off the coast of Uruguay on Dec. 13, 1939.

Damaged and lacking fuel to get home, the ship was scuttled, its crew, including Schauenburg, taken captive. Schauenburg escaped twice and made his way across Argentina disguised as a cloth merchant but was recaptured both times. After his release was negotiated, he returned to Germany and enlisted in the U-boat service in 1941.

Unlike Kretschmer, Schauenburg, 33, was not beloved by his crew.

While naval discipline was relaxed for other U-boat crews, given the dirty, cramped, hot environment of undersea service, Schauenburg insisted on tight discipline, proper dress and hygiene. He was a fanatic and idealistic Nazi, one crewman told interrogators.

And he wasn’t first choice for the mission: two other U-boats were lost before they could carry out the assignment in Canada.

But his skill brought him safely and on time to Chaleur Bay off the coast of New Brunswick to pick up German escapees from Camp 30 in Bowmanville, Ont. His savvy helped him to avoid the Allied trap that awaited him, and his coolness allowed him to escape a dragnet of 10 Allied warships, keeping as close to shore as possible and barely submerged, listening to the search overhead through hydrophones. He made it to the Atlantic, but not to safety.

U-536 joined a wolf pack dogging a convoy northeast of the Azores, making its way to Gibraltar on Nov. 20, 1943. Low on fuel and out of torpedoes, the sub was submerged when pinged by three convoy escort ships, HMC ships Snowberry and Calgary and HMS Nene.

Snowberry dropped two rounds of depth charges at different depths.

“If it did not damage the U-boat, at least it shook it up badly,” said Snowberry’s commander Lieutenant J.A. Hamish Dunn, quoted in Michael L. Hadley’s U-Boats Against Canada.

The sub was, in fact, badly damaged. When it broke the surface, “a gun’s crew raced out of the conning tower towards their gun. You could see our 20mm tracer bullets fanning behind them before they jumped over the side. Another crew immediately followed with the same fate,” said Leading Seaman Frank Moss of Calgary, quoted in Mac Johnston’s Corvettes Canada.

“In retrospect, it was very sad,” added Calgary’s Mac Orr. “If she had not tried to fight the three of us and just surrendered, instead of saving 18 lives we probably would have saved the whole crew.”

Schauenburg spent the remainder of the war in a PoW camp in Quebec.

Unsuspecting escapee

U-boat ace Wolfgang Heyda managed to capitalize on a fellow prisoner of war’s bad fortune.

After Otto Kreschmer and the other would-be escapers of Operation Kiebitz were arrested, Heyda, whose name had not been on their list, foiled camp surveillance with technology from the age of sail.

Utility wires straddled the barbed wire perimeter fence at the German PoW camp in Bowmanville, Ont., suspended from poles on either side. As his ticket to freedom, Heyda planned to use a bosun’s chair—a plank suspended by ropes used historically to hoist sailors high into the rigging.

Heyda used homemade linesman’s crampons to climb the poles, manoeuvre a jury-rigged bosun’s chair along the wires and over the fence, then climb down the pole outside the camp.

He made his escape on Sept. 24, 1943, while fellow PoWs distracted the guards. Dressed in civilian clothes and supplied with money meant for Kreschmer’s crowd, he made his way by train from Bowmanville to New Brunswick.

He posed as Fred Thomlinson of Toronto, a recently discharged army engineer, on his way to New Brunswick to do geological surveys for the navy. His false travel documents had forged signatures of a Canadian admiral. His papers were so good that he passed through a police cordon near his destination with only a warning not to walk on the beach late in the evening.

Not suspecting anything was awry, he did walk on the beach, where he met a Canadian army welcoming party on the lookout just for him. He was arrested within sight of the rendezvous point.

Heyda spent the remainder of the war in Camp 30. He died of polio just three months after his release in May 1947.

Advertisement