They were dark and uncertain times in 1943 when two American composers, Hugh Martin and Ralph Blane, wrote a hopeful little song that would become an all-time hit of musical cinema—and of the ever-expanding Christmas season.

Crafted for the 1944 film Meet Me in St. Louis, in which it was first sung by Judy Garland, the bittersweet “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas,” it turns out, is at its heart a more hopeful treatise on war and loneliness than the movie storyline would suggest.

Around the time the song was written, a desperate Soviet Red Army was beating down German troops in Stalingrad, Jews mounted a doomed uprising in Poland’s Warsaw Ghetto, the war in the Pacific had begun its long march north to Japan, British forces captured Tripoli, and HMCS Ville de Quebec sank U-224 in the Mediterranean. And that was just during the month of January.

Of course, neither the song nor the movie makes any outward reference to the war.

The lyrics make unmistakable links to the universal experience.

“Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” appeared in a scene in which a family is distraught over the father’s plan to leave their cherished home in St. Louis for a job promotion in New York. On Christmas Eve, Garland’s character, Esther, sings it to cheer up her despondent sister, five-year-old Tootie (Margaret O’Brien).

But the lyrics make unmistakable links to the universal experience of innumerable families, friends and loved ones across nationalities and throughout the annals of war, touching on separation, loss, melancholy and fate.

It was a song for its time, and all time, even these COVID times.

It assures that “your troubles” will pass, that “happy golden days of yore” will return and “faithful friends who are dear to us” will “gather near to us once more.” “Through the years,” it declares, “we’ll always be together if the fates allow.”

Some of Martin’s original lyrics were rejected at the outset, the principal composer wrote in his autobiography, The Boy Next Door. At first sight, before filming began, Garland, co-star Tom Drake and director Vincente Minnelli dismissed the draft lyrics as depressing and asked a reluctant Martin to change them.

He eventually rewrote some to make the song more upbeat. For example, the ominously dark lines “It may be your last/Next year we may all be living in the past” became “Let your heart be light/Next year all our troubles will be out of sight.”

Garland’s single of the much-recorded song, released by Decca Records, reached No. 27 on the Billboard charts and became a hit among troops overseas. Her performance of the three-minute, 16-second piece at the Hollywood Canteen—a wartime club for departing service personnel—brought troops to tears.

But “Merry Little Christmas” wasn’t the only 1940s Christmas song to achieve immortality—not by a longshot. Indeed, the decade is considered the Golden Age of secular Christmas music—an era of conflagration in which bittersweet sentimentality struck a chord at the war front and home front alike.

In 2014, the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) released its list of the Top 30 most-performed holiday songs of all time. A third—that’s 10 of them—were written in the 1940s. Another nine came from the postwar decade of the 1950s, when all those repatriated servicemen who weren’t destined for Korea and their sweethearts were engineering the baby boom.

“Indisputably, World War II and the immediate postwar years represented something of a golden age for Christmas music, with the 1940s and 1950s accounting for nearly two thirds of ASCAP’s most popular songs,” Molly Fitzpatrick wrote for the online news site vocativ.

“This may seem trivial: The older a song is, the more opportunities time will have afforded it to be performed again and again. But ASCAP’s century-spanning list contains only three songs from the ’30s, and none from the ’20s or ’10s.”

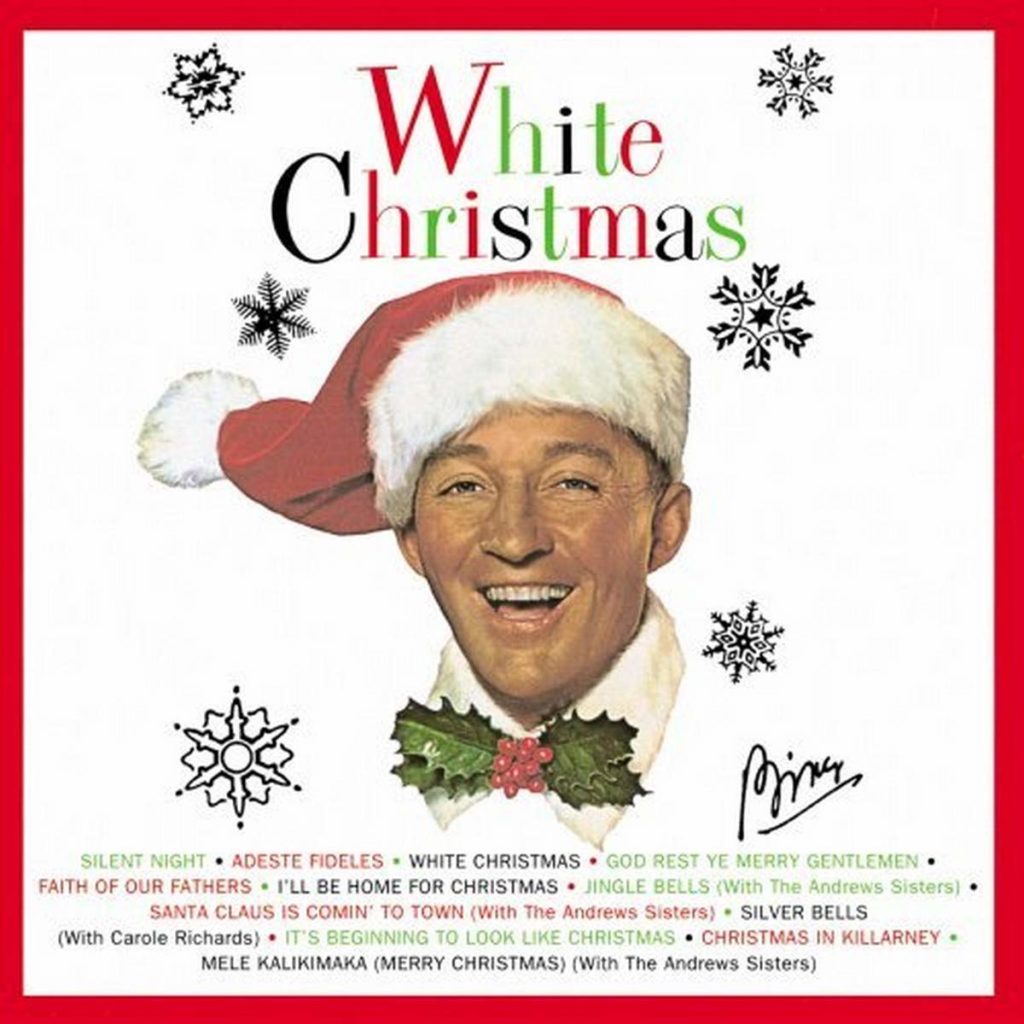

Three of the Top 5 songs come from the wartime 1940s: at No. 2, “The Christmas Song (Chestnuts Roasting on an Open Fire),” which Mel Tormé wrote during a blistering hot summer in 1945; at No. 3, 1940’s “White Christmas,” which Irving Berlin called not only “the best song I ever wrote, it’s the best song anybody ever wrote;” and at No. 5, Martin’s “Merry Little Christmas.”

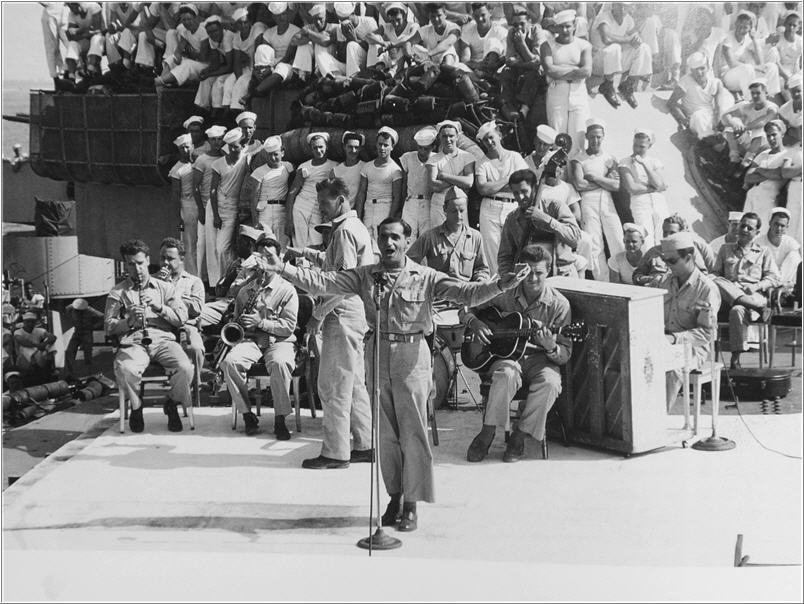

The prolific and talented Irving Berlin entertains aboard the USS Arkansas in 1944.[Wikimedia]

Crosby “accomplished more for military morale than anyone else of that era.”

Perhaps the most poignant song on ASCAP’s all-time list is “I’ll Be Home for Christmas,” written by lyricist Kim Gannon and composer Walter Kent. It was recorded by Bing Crosby in 1943—his second straight holiday hit of the war, after “White Christmas” was officially released in 1942.

“I’ll Be Home” came in at No. 10 but, in terms of lump-in-your-throat sentimentality, it’s tough to beat.

“Christmas eve will find me/Where the love light gleams,” crooned Crosby. “I’ll be home for Christmas/If only in my dreams.”

A heart-wrencher with a stirring melody, it became the most requested song at holiday USO shows and helped inspire the GI magazine Yank to write that Crosby “accomplished more for military morale than anyone else of that era.”

The song’s morale-boosting properties were a matter of some dispute, however.

While “I’ll Be Home” struck a chord in theatres of war and at home in many countries, Britain’s national broadcaster, the BBC, banned it from the airwaves out of apprehensions that the lyrics might undermine morale among British troops.

Written for the film Holiday Inn, “White Christmas” is the iconic piece that started it all rolling, according to industry experts.

PBS Newshour said in 2018 that what would become Bing Crosby’s signature song established that there could be commercially successful secular Christmas music.

“During the 1940s, ‘White Christmas’ would set the stage for a number of classic American holiday songs steeped in a misty longing for yesteryear,” music industry writer Ronald D. Lankford Jr. said in his 2013 book Sleigh Rides, Jingle Bells, and Silent Nights: A Cultural History of American Christmas Songs.

Before 1942, wrote Langford, Christmas songs and films had come out sporadically. Although many were successful, “the popular culture industry had not viewed the themes of home and hearth, centered on the Christmas holiday, as a unique market” until after the song’s and film’s success.

Crosby unveiled “White Christmas” to the public on his NBC radio show The Kraft Music Hall, broadcast on Christmas Day 1941. The iconic singer is said to have initially misjudged its potential, telling Berlin after an 18-minute recording session five months later: “I don’t think we have any problems with that one, Irving.”

“White Christmas” became the most-recorded Christmas song ever, with more than 500 versions in multiple languages. Crosby’s version, which he re-recorded in 1947 after the 1942 master was damaged, has been crowned by the Guinness Book of World Records as the world’s best-selling single, of any genre, with over 50 million copies sold worldwide. It spent 11 weeks atop the 1942 charts and became the title of a second film in 1954—starring none other than Bing Crosby.

All of which begs the question: How could it only place third on ASCAP’s most-played list?

Crosby sloughed off any role he might have played in the song’s success, insisting later that “a jackdaw with a cleft palate could have sung it successfully.”

“He had to stand there and sing ‘White Christmas’ with 100,000 GIs in tears.”

Crosby’s nephew, Howard Crosby, once asked his uncle about the most difficult thing he ever had to do during his entertainment career.

“He said [that] in December 1944, he was in a USO show with Bob Hope and the Andrews Sisters. They did an outdoor show in northern France.

“He had to stand there and sing ‘White Christmas’ with 100,000 GIs in tears without breaking down himself. Of course, a lot of those boys were killed in the Battle of the Bulge a few days later.”

Advertisement