Author Lech Kwasiborski in Eygpt in 1974, serving with the UN Emergency Force II. [Lech Kwasiborski]

Each year as summer approaches, my memory takes me back to Aug. 9, 1974. It has taken me 50 years to memorialize this day in words. The framing of my experience that day led me into deep reflection. How do I tell this story without making it about me and some long-forgotten event and more about the self-sacrifice of others?

I realized that without mentioning myself, I would just be introducing historical fact without human feeling and, since we all share emotions, hopefully you will experience the underlining tone.

I joined The Royal Montreal Regiment army reserves in the spring of 1970 at the age of 16. In the summer of 1971, I was at Canadian Forces Base Valcartier for my infantry training. From February to April 1972, I was at CFB Edmonton (Griesbach Barracks) for additional training before deploying to Jamaica with The Canadian Airborne Regiment, 1 Commando, for a jungle warfare exercise named Nimrod Caper. In the summer of ’72, I was attached to NATO with the 1st Battalion of the Royal 22e Régiment in Europe at CFB Lahr, Germany.

On Oct. 6, 1973, the Yom Kippur War broke out between Israel and an Arab coalition lead by Egypt and Syria. Initial Arab advances were stymied by Israeli forces in the Golan Heights and when an armoured Israeli column crossed the Suez Canal on Oct. 21, threatening the encirclement of the Egyptian Third Army around Suez City.

The Soviet Union and the U.S. requested an urgent session of the UN Security Council to discuss a ceasefire. Resolution 339 was confirmed on Oct. 23. The fighting continued, however, and Egyptian President Anwar Sadat asked the Soviets and the Americans to intervene directly. The U.S.S.R. agreed, but the U.S. refused. On Oct. 24, Egypt requested that the Security Council reconvene.

The next day, a proposal by non-aligned members of the council was accepted and Resolution 340 demanded an immediate ceasefire and a return to positions occupied by the warring parties as of 4:50 p.m. on Oct. 22. The United Nations Emergency Force II (UNEF II) was created to supervise it.

Canada and Poland were approached to provide logistical support and, by mid-November, NATO-member Canada Warsaw Pact-member Poland sent advance parties to Cairo to prepare for the arrival of international contingents from Austria, Finland, Ghana, Indonesia, Ireland, Nepal, Panama, Peru, Senegal and Sweden.

In the fall of 1973, a memo was sent from Canada’s Defence Department to all primary reserve units requesting qualified volunteers for full-time service to augment the regular forces assigned to UNEF II. As a newly promoted corporal with previous overseas experience, I was accepted, along with a close friend, Corporal Henry (Harry) Hall (future colonel and commanding officer of our regiment).

We were among the first reservists deployed on a UN mission. We were posted to 5 Brigade in Valcartier in late-January 1974 for evaluation, training and qualification. Upon successfully completing our courses, we departed for the Middle East and arrived in Cairo the last week of April.

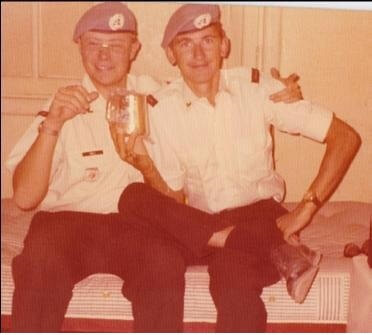

Corporal Henry (Harry) Hall and author Kwasiborski. [Lech Kwasiborski]

We were based at the Nadi Shams racetrack, on the city’s eastern outskirts, about 11 kilometres from the airport. I was posted to 73 Service Unit, General Duty Platoon, and Hall was assigned to headquarters admin. My duties ranged from camp security, transportation, setting up and taking down tent lines and a variety of other daily tasks. Once word got around, however, that I spoke English, Polish and French, I got a new and more interesting role serving as a liaison between the Canadian and Polish militaries.

Acting Master Warrant Officer Cyril Bogdan Korejwo of The Royal Canadian Regiment was my company sergeant-major and would soon become a friend. He was a 20-year veteran of the Canadian Army and 27 years my senior. We shared Polish heritage, pride in the military and mistrust of anything Soviet.

Korejwo was born in Poland in 1927. During the Second World War, he had been sent to Germany as a child labourer. Postwar, he was unofficially adopted by the Canadian Army, who feed, clothed, protected and nurtured him. Korejwo told me he moved to Canada in January 1954 and enlisted in its army to repay the goodwill.

My first reality check of the tour came at Nadi Shams on July 10, 1974. Dozens of troops, both Canadian and foreign, were sitting in the racetrack’s stands just before sunset awaiting the showing of a recent Hollywood movie on a large canvas screen. Suddenly, we noticed a Tupolev Tu-154 flying straight up from the Cairo International Airport just beyond the right side of the screen. The plane stalled and started to descend tail first, then turned into a nose-dive before crashing in a huge fireball.

Four Soviets and two Egyptian pilots perished in the training flight, the incident reportedly caused by pilot error.

A second nearby crash occurred about a week later. I was in the company transport tent on the morning of July 19 doing some administrative work and preparing my truck for a trip to Ismailia, a city on the western bank of the Suez Canal. I had become accustomed to the sounds of early morning flights of Egyptian military transport planes over our base but, on this day, the noise of one aircraft was off; it was much louder, like a sputtering roar.

I ran outside and looked up. An Ilyushin 14 was about 30 metres above me. I watched in stunned horror as the plane looked like it was about to crash into the racetrack, which housed our main administrative offices and quartermaster facilities. My friend Hall worked in there with dozens of other personnel.

I watched as the plane dipped its left wing, thus raising its right wing and clearing the three-storey building. Seconds later, however, it slammed into the ground and skid into a brick wall, exploding in a roar and thick black smoke. I ran toward the crash and seconds later standing about 12 metres from the wreckage. The intensity of the heat was incredible, and the sight of the unconscious pilot being consumed by the flames unbearable.

Sirens blared, Egyptians were screaming and crying. One crewman who had been thrown out of the aircraft was carried by three Canadians to a Polish ambulance and driven away. Unfortunately, he and the other four Egyptian crewmen died. I wholeheartedly believe that their evasive manoeuvre just before the crash saved dozens of Canadian lives.

An Ilyushin 14 belches black smoke after crashing in Cairo near the UN base in 1974. [Lech Kwasiborski]

I had a third close call with a plane crash that summer. Air transportation for UNEF II involved three Buffalo CC-115 aircraft based at the old British airfield in Ismailia. The planes were also tasked with supporting two other UN missions in the region, including the forces in Cyprus and Syria.

In addition to its official duties, the air unit would take Canadian personnel for short stays to Beirut if space allowed. I had requested a seat for one of those trips and was authorized for a flight in early August.

I was looking forward to the trip and a few days of R and R in the Lebanese capital, but in late July, Korejwo told me I had been bumped off the flight. He and his replacement, newly arrived Master Warrant Officer Gaston Landry, were going instead. He noted that it would be a perfect time for him to bring Landry up to speed. Korejwo also told me that I was to pick them up the next morning and drive them to the airfield.

Now, on July 20, hostilities had broken out in Cyprus causing flight routing problems. The air transport unit had to adhere to precise air corridors and times. Still, on Aug. 7, I delivered Korejwo and Landry to UN Flight 51, the trip I was originally slated to join. But they never made it back. Their Buffalo was shot down by three Soviet-made surface-to-air missiles fired from Syria on their return flight on Aug. 9.

Korejwo and Landry were killed, along with seven other Canadian peacekeepers, including captains George Foster, Keith Mirau and Robert Wicks, Master Corporal Ron Spencer, corporals Bruce Stringer, Michael Simpson and Morris Kennington.

When I heard the news, I was stunned. I’m ashamed to say that, at first, I was glad that I got bumped. My thoughts ran wild. Had I been on that flight would there have been a different outcome? Would something as small as my being present change the future for my fellow peacekeepers? Or had Korejwo saved my life and unknowingly suffered a tragic end to his own?

I returned to Montreal in December 1974 and went back to school. I stayed in the reserves until 1999, then worked in the computer industry. I married in 1990 and had two beautiful daughters. I retired at 67, but returned to work two year later as the assistant manager of the Last Post Fund National Field of Honour military cemetery in Pointe-Claire, Que. I’m thankful I survived that deadly summer and the worst day of fatal casualties in the Canadian military since the Korean War.

Aug. 9 is now National Peacekeepers Day. By the end of the summer of 1974, Canada lost 11 peacekeepers, four military personnel in active training and six cadets. It took me until three years ago to come to terms with Korejwo’s sacrifice. That’s when I located his gravesite and I have now visited him each August since at Ontario’s Alliston Union Cemetery.

I remember him. I remember them.

Advertisement