Victorious troops return from Vimy Ridge, the first battle where all four Canadian divisions fought together. Two Cantleys, both named Robert and both born in Aberdeen, Scotland, and both fighting in Canadian uniforms were wounded at Vimy. Like so many soldiers of a young and growing Canada, they were labourers, one a bridge builder, the other a railroader. [LAC/PA-001270]

There were just eight Cantleys and one Cantlie.

According to their service records posted online by Library and Archives Canada, some were born overseas, yet they hailed from a wide swath of their adopted Canada, enlisting in Nova Scotia, Quebec and Manitoba. From bridge-builder to prospector to railroader, they reflected the core trades and values of a growing, developing country of fewer than eight million people.

Most were privates, earning a mere $15 a month—about $500 today. Two brothers made officer, another was a decorated lieutenant-colonel.

Their destinies in wartime France included decisive battles and covered the gamut of fates, from gunshot and shrapnel wounds to influenza, venereal diseases and shell shock. One was gassed. Two caught bullets at Vimy Ridge and lived to tell the tale.

For one Cantley, the war ended before it started. Another was killed in one of his first battles.

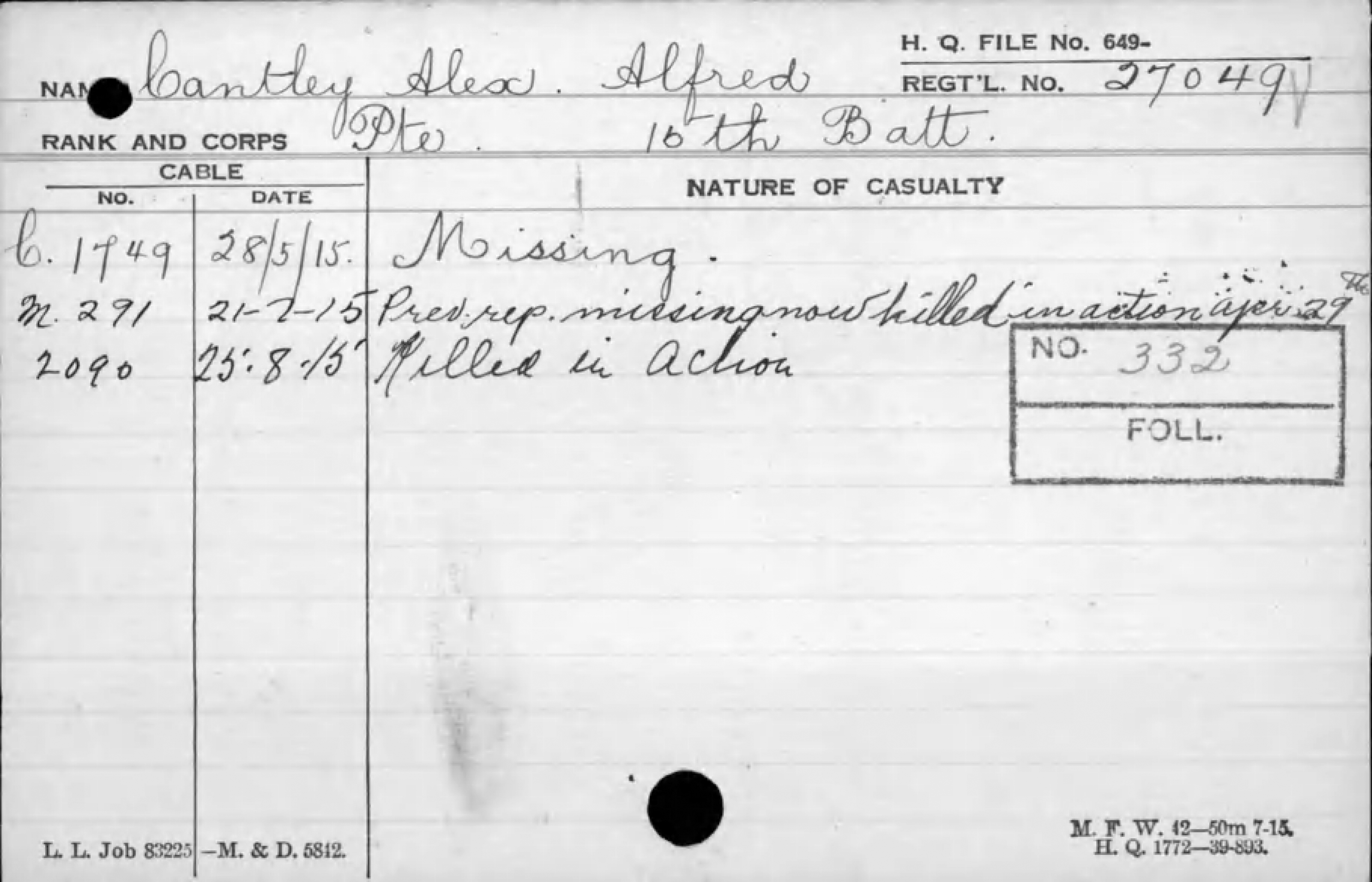

His name was Private Alexander Alfred Cantley, a prospector born in Kilkenny, Ireland. He enlisted at Valcartier, Que., on Sept. 18, 1914, arrived in France with the 15th Battalion (48th Highlanders of Canada) in early 1915, and died during the Second Battle of Ypres on April 29. No details of his fate are given in his 28-page service record. The location of his death is marked simply as “field.” He was 29.

Private Alexander Alfred Cantley, a prospector born in Kilkenny, Ireland, enlisted at Valcartier, Que., on Sept. 18, 1914, and died seven months later at Ypres. He was initially reported missing after the battle, then declared dead. He was 29. (Click to enlarge) [Library and Archives Canada]

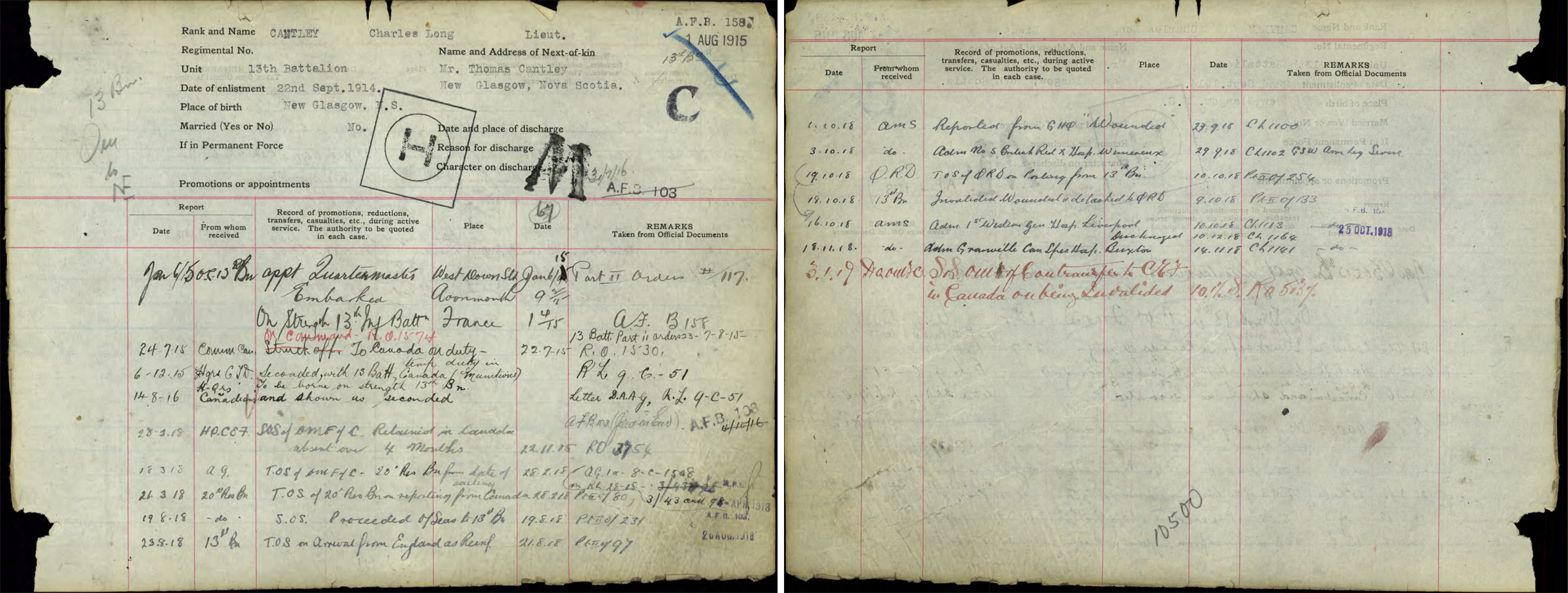

Lieut. Charles Lang Cantley, a mining engineer from New Glasgow, N.S., was wounded by exploding shell fragments outside Cambrai in 1918. He was left with multiple scars and a permanent limp. There was still shrapnel in his body when he died in 1935 at just 51 years old. (Click to enlarge) [Library and Archives Canada]

A member of the 13th Battalion (Royal Highlanders of Canada), Charles was also wounded in the right wrist and below his right eye. He was declared disabled on June 7, 1919, and invalided to Canada. There was still shrapnel in his body when he died in July 1935 at just 51 years old.

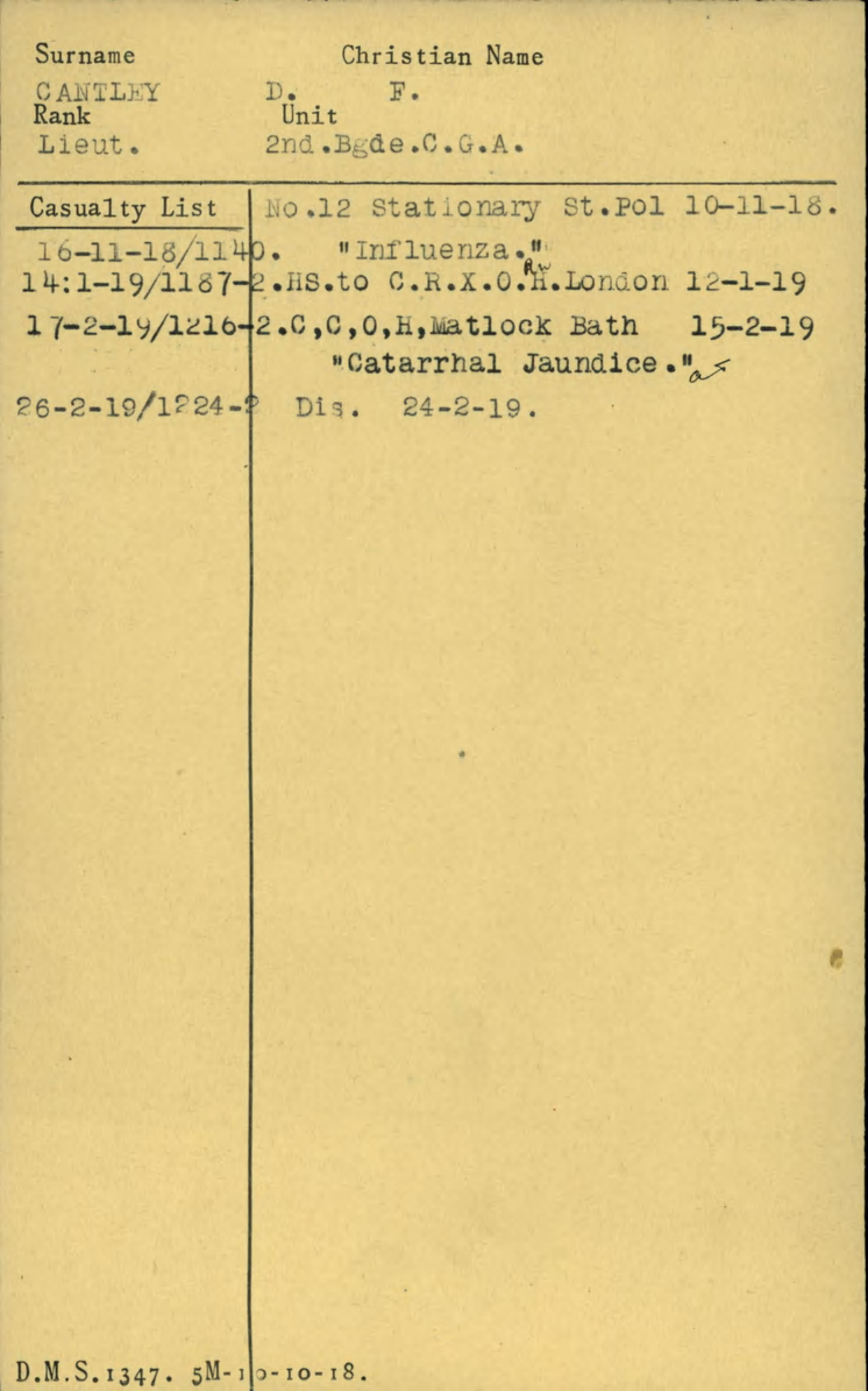

His brother Donald, a student when he signed up, was Mentioned in Dispatches—for what, the records don’t say—and survived two bouts of influenza, in 1918 and again in 1919, before he was shipped home with jaundice.

Charles Cantley’s brother, Lieut. Donald Fraser Cantley, survived two bouts of influenza before he was shipped home with jaundice. Cold, exposure, filth, lack of personal hygiene, poorly preserved food and an absence of sewage disposal contributed to the spread of germs, bacteria and viruses. The Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 killed thousands. (Click to enlarge) [Library and Archives Canada]

His war record is sketchy, noting brief service in England and, it appears, at defence headquarters in Rouen in 1915. The Canadian records ended abruptly when he was apparently transferred to the British Expeditionary Force.

Thomas Cantley headed a steel plant and Nova Scotia Archives records say that he travelled extensively throughout Europe between 1895 and 1919 marketing Wabana iron ore and coal. They say he was instrumental in launching wartime production of ammunition for Great Britain.

He went on to become a Tory MP after the war, representing his Pictou-area riding from 1925 into the mid-1930s. He was appointed to the Senate in 1935, where he served until he died a decade later.

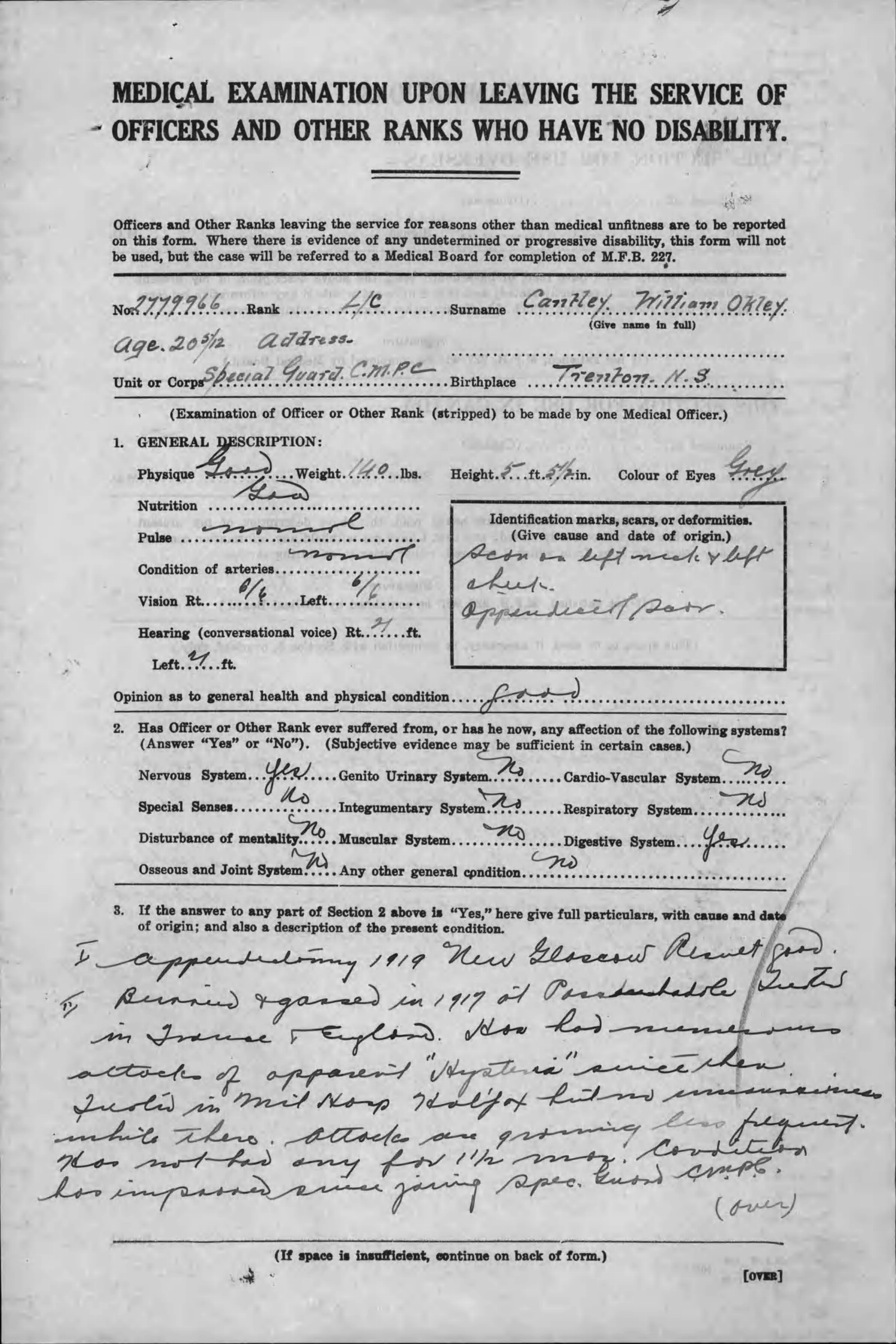

At 18 and just five-foot-five-and-a-half, 105 pounds, William Okley Cantley was the youngest of the Cantleys to join up. He was a flat-footed steelworker from Trenton, N.S., when he enlisted in March 1916.

At 18, William Okley Cantley of Trenton, N.S., was the youngest of the eight Cantleys to join up. He was gassed 20 months later at Passchendaele and discharged in 1920. He’d be in and out of hospital with “hysteria” for years. (Click to enlarge) [Library and Archives Canada]

A lance-corporal, he was later diagnosed with gonorrhea and arrived back in Halifax on April 10, 1919, a sick man. The youngest serving Cantley was discharged in 1920. He would be in and out of hospital with “hysteria” for years after.

“Loses consciousness when he has these seizures and does not know what he is doing,” said a medical report written at the Cogswell Street Hospital in Halifax on Feb. 5, 1920. “They are preceded about 10 minutes by a sensation of ball rising in throat and choking him.”

Later reports indicated his condition was improving and the incidents were occurring less often.

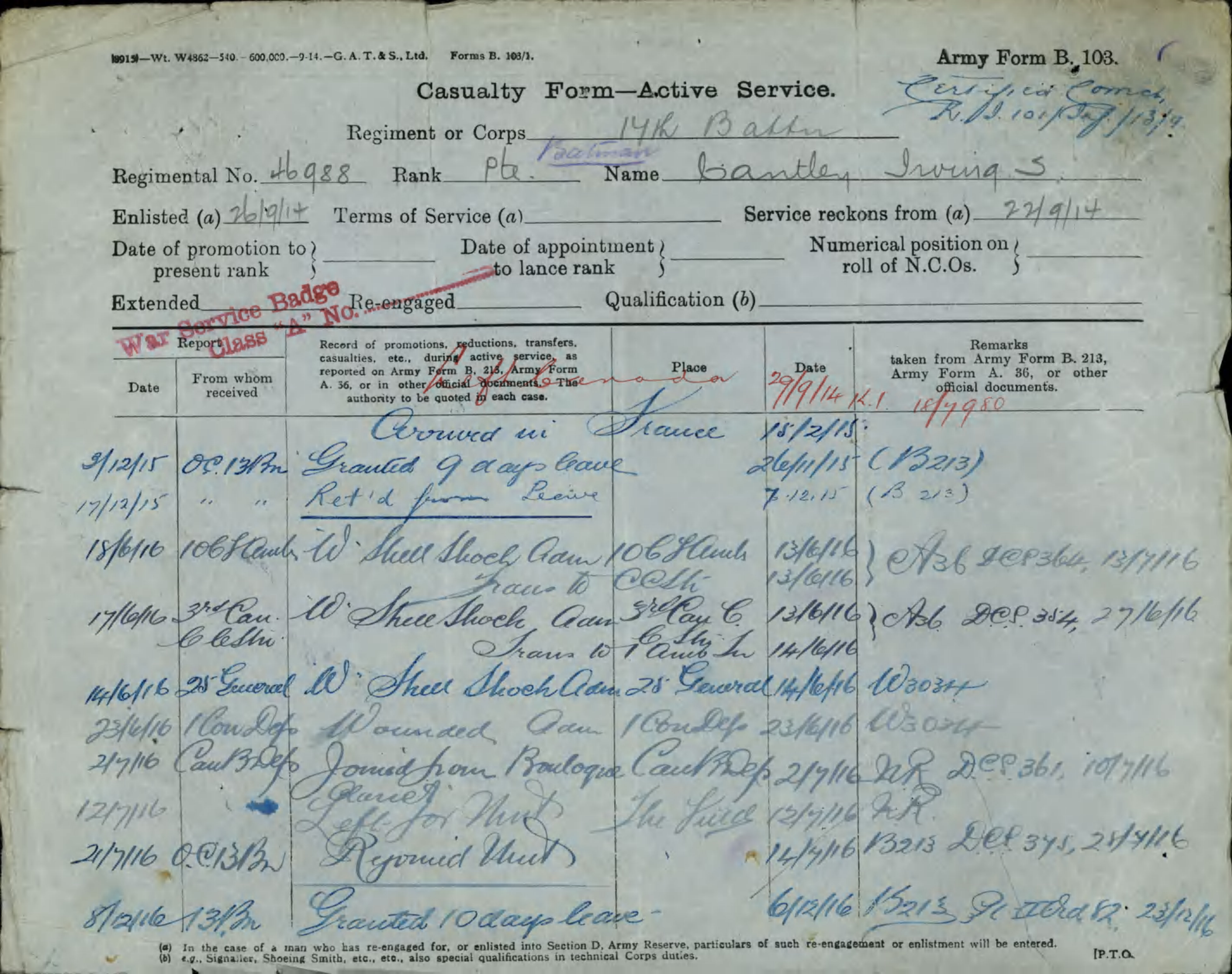

Just five-foot-four, Irving Seeley Cantley, 20, was a steelworker from New Glasgow, N.S. He served with the 13th Battalion (Royal Highlanders of Canada), and on June 14, 1916, 21 months after he had enlisted, he was struck down by shell shock.

Just five-foot-four and 20 years old, Irving Seeley Cantley was struck down by shell shock in June 1916. He returned to action at the Battle of the Somme a month later and shipped back to Canada with an English bride, Louise, in April 1919. Countless First World War veterans suffered mental illness, exacerbated by the fact the science of psychiatry was still in its infancy. (Click to enlarge) [Library and Archives Canada]

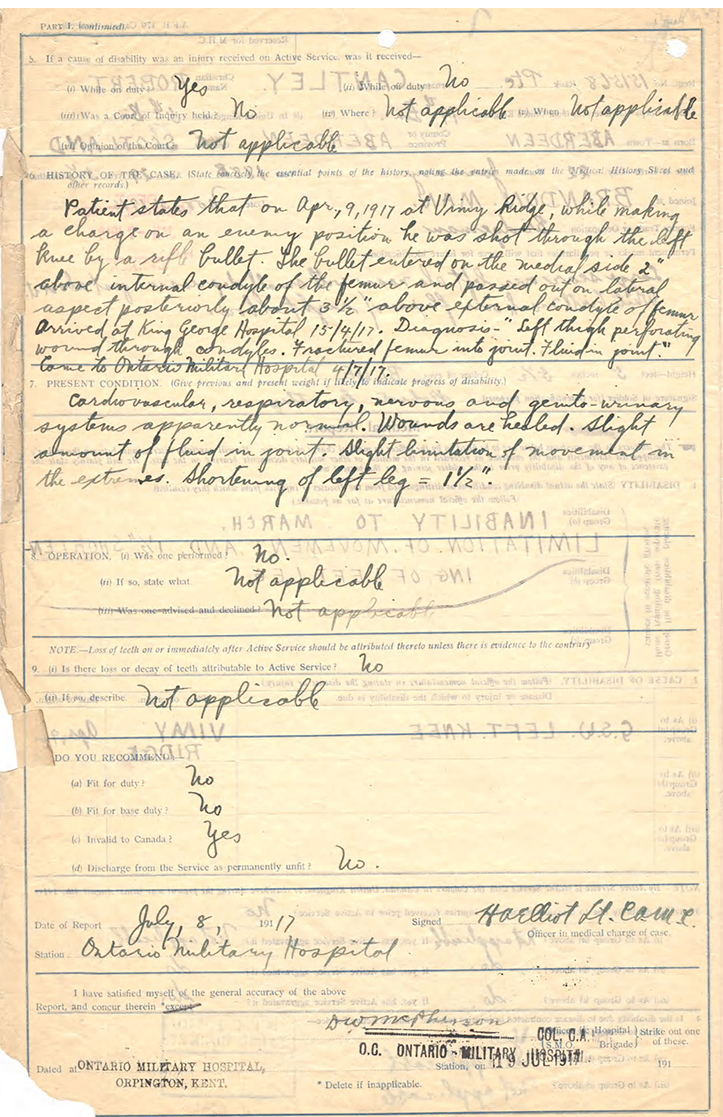

There were two Robert Cantleys—a 19-year-old bridge builder from Brandon, Man., and a 28-year-old railroader from Winnipeg—and both were wounded on the first day of battle at Vimy Ridge, April 9, 1917.

Both were born in Aberdeen, Scotland. Whether they were related is unknown.

Robert Cantley the bridge builder from Brandon, Man., took a rifle round through the knee at Vimy Ridge, leaving his left leg one-and-half inches shorter than his right. He returned home aboard the hospital ship Llandovery Castle. A year later, 234 of 258 aboard were killed when the ship was sunk by a German torpedo. (Click to enlarge) [Library and Archives Canada]

He spent a week in a French hospital, then six months in a British hospital and a further six weeks in a Canadian hospital. He returned home aboard the hospital ship Llandovery Castle, which a year later would be sunk by a German torpedo; 234 of 258 died, many when the U-boat crew machine-gunned survivors.

“Left leg is one and half inches shorter than right,” said a report made back in Winnipeg before Cantley was discharged on Nov. 13, 1917, two years to the day after he enlisted. “There is movement of the knee joint to a right angle…. No pain or swelling present…. Can walk two miles without tiring.”

His official reason for discharge, however: “INABILITY TO MARCH.”

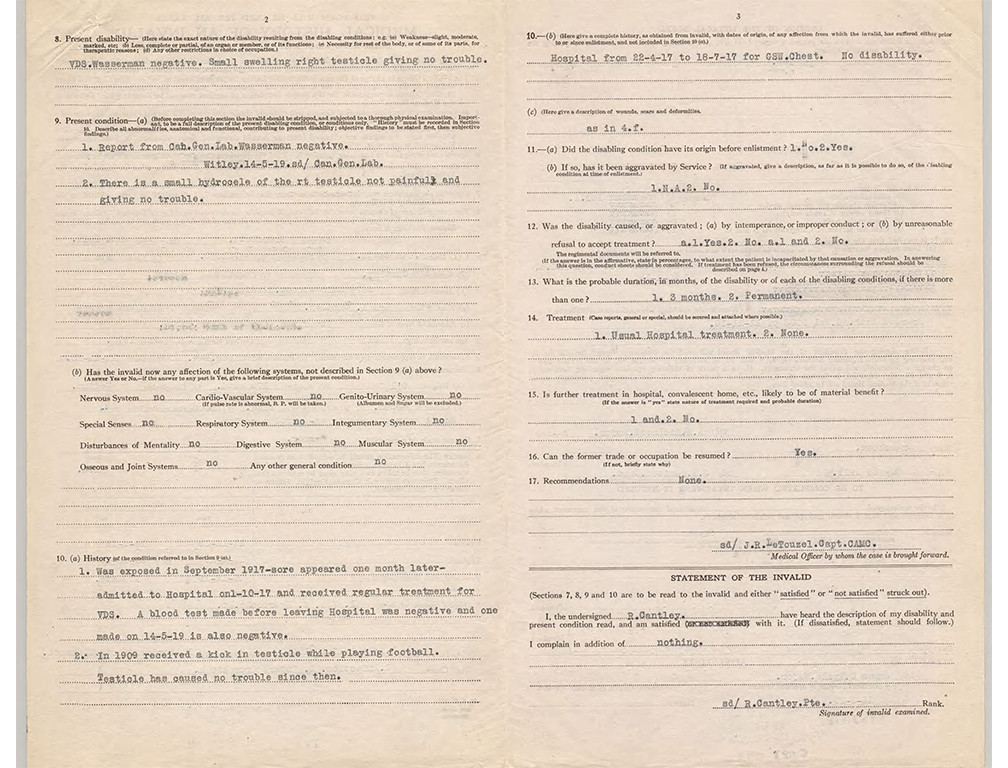

Robert Cantley the railroader from Winnipeg was shot clean through the chest while serving with the 78th Battalion at Vimy. He survived, only to contract venereal disease five months later. He returned to duty and made it home to Canada in 1919. (Click to enlarge) [Library and Archives Canada]

He returned to duty and made it home to Canada in 1919. His last medical, dated May 28, 1919, noted that he had been kicked in the testicles during a football game in 1909 and his right one was still swollen.

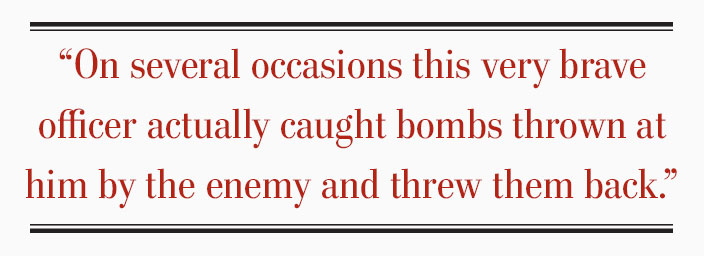

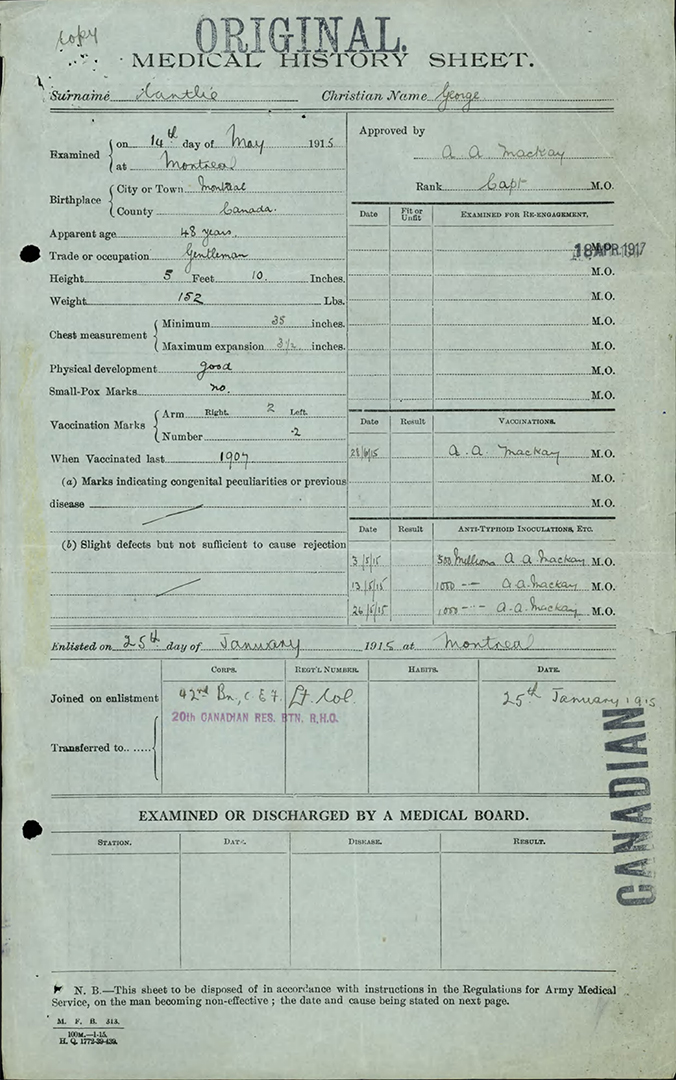

The one Cantlie who fought for Canada in the First World War was Lieutenant-Colonel George Stephen Cantlie of Montreal. His attestation papers, signed when he joined up at age 48 in 1915, listed his occupation as “Gentleman.”

Col. George Stephen Cantlie of Montreal listed his occupation on sign-up as “Gentleman.” The first commander of the 42nd Battalion, Royal Highlanders of Canada, he is remembered for pressing flowers from French battlefields and sending them in letters to his baby daughter Celia. (Click to enlarge) [Library and Archives Canada]

Cantlie wrote two letters nightly—one to wife Beatrice and a second to one of his five children. Celia was the youngest.

Cantlie and his daughter Celia. [warflowers.ca]

The first commander of the 42nd Battalion (Royal Highlanders of Canada), he was awarded a Distinguished Service Order and was Mentioned in Dispatches “for distinguished and gallant services and devotion to duty” in 1916.

Cantlie took a leave of absence and shipped himself home in 1917, returning to England four months later. He did not return to the front, but was appointed commanding officer of the 20th Reserve Battalion, responsible for providing reinforcements to Montreal-based front line battalions.

His daughter Celia grew up adoring him, as did his granddaughter, Elspeth, to whom Celia bequeathed a red box full of his letters.

The WAR Flowers exhibition is currently at Château Ramezay Museum in Montreal, until March 31. Learn more about the exhibit at: https://warflowers.ca

Advertisement