Mary Riter Hamilton’s “No Man’s Land, 1920.”[Mary Riter Hamilton/LAC/1988-180-113]

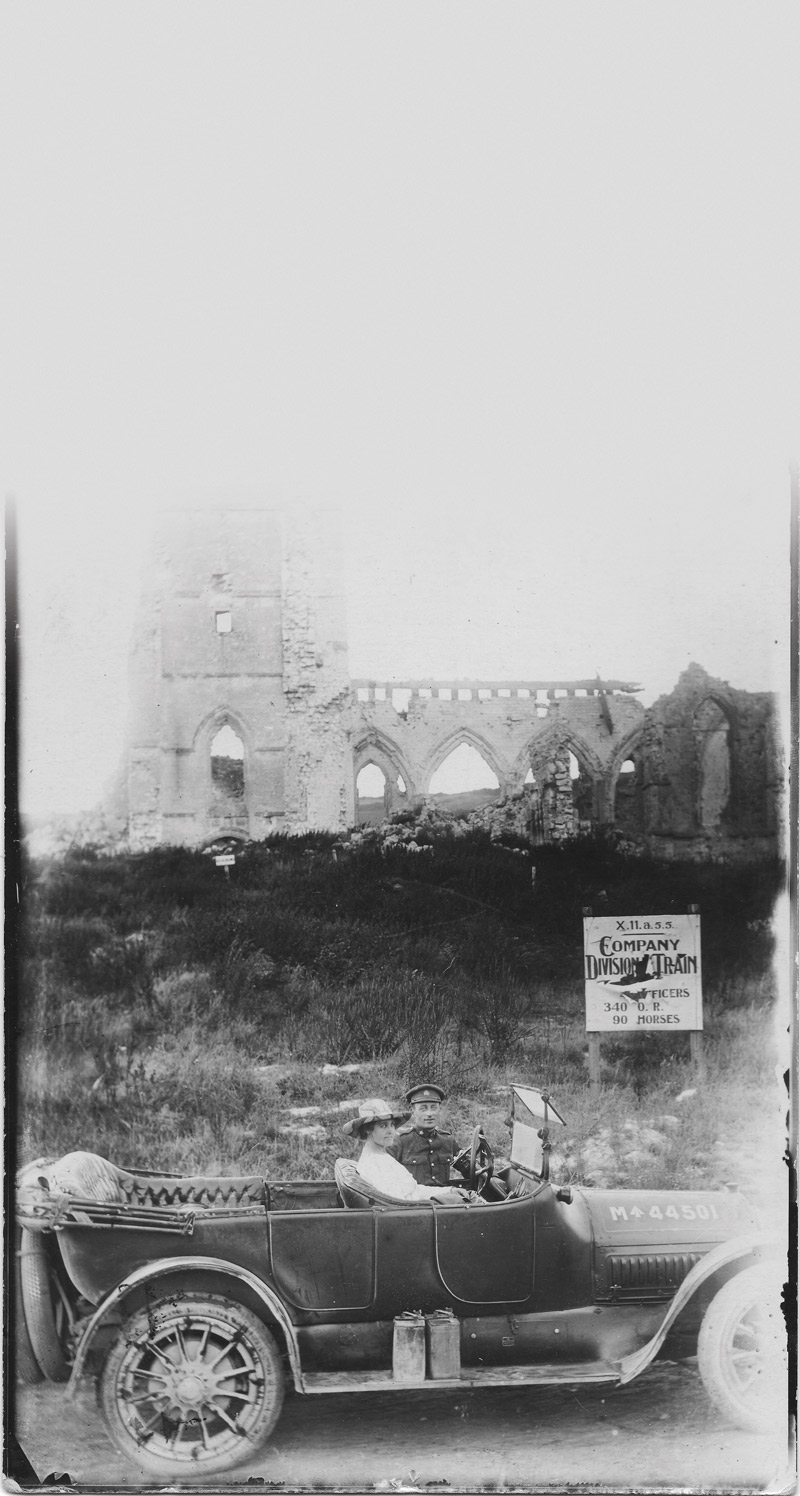

Hamilton’s “War Material.” A photograph of the artist in B.C. circa 1913-14 and during her visit to the Western Front in 1919.[Mary Riter Hamilton/LAC/2894951]

Hamilton’s “War Material.” A photograph of the artist in B.C. circa 1913-14 and during her visit to the Western Front in 1919.[Mary W. Higgins Collection, Victoria, B.C]

“I cannot talk, I can only paint.” The motto driving the Canadian battlefield painter Mary Riter Hamilton during her First World War expedition conveyed a sense of urgency.

Despite rejections in May 1917 and January 1918 from the Canadian War Memorials Fund, Hamilton, born in 1867, remained resolute in her pursuit to become a war artist. In early 1919, she secured a commission from the Amputation Club of British Columbia to document the post-Armistice Canadian war sites in Europe. Embarking on this venture at the age of 51, she boldly presented herself as 35 on her passport. Having first reinvented herself as a painter after her husband’s death, defying the sexist and agist boundaries, this was a signature move.

[Courtesy Ronald T. Riter]

From April 1919 to November 1921, Hamilton visited the postwar trenches and bombed villages of northern France and Belgium, painting and drawing her own witnessing of places where Canadian soldiers had fought and perished. Despite desolation, dangers and hardships, the result was an exceptional collection of 320 war paintings and sketches in oil, as well as drawings in pencil, charcoal and a few etchings.

“It is hardly necessary to say—certainly it is unnecessary to say it to those who knew this area at that time—that the work was done for love.”

Hamilton’s motivation for her singular expedition becomes clear in her candid words: “It is hardly necessary to say—certainly it is unnecessary to say it to those who knew this area at that time—that the work was done for love; for the love of those who had fought and fallen ‘in Flanders’ fields’; for love—and, if it might be, to help perpetuate the memory of the sacrifice, and to comfort, if possible, some who were bereft.”

Hamilton’s deep sense of purpose stemmed from a series of personal tragedies, including the early deaths of her husband, son, sisters, brother and her niece Matilda Green, who served as a war nurse in Étables, France. Those losses manifest her deep empathy and her commitment to documenting the immense scale of death.

Her art being her primary focus of expression, her widowed and childless status gave her freedom to undertake her expedition without family restrictions. While a rare photo shows her in a car [2], mostly she walked on foot, criss-crossing enormous distances and navigating through wartorn swampy landscapes, often filled with unexploded ordnance. Her experience in the trenches and amid the desolation of ruined villages served as a catalyst, profoundly transforming both Hamilton and her artistic style. What sets her apart from conventional war artists is her phenomenological approach.

[Mary Riter Hamilton/LAC]

[Mary Riter Hamilton/LAC]

Living in a primitive shack at Écurie in the southern district of Vimy Ridge, she recorded, and warned of, the consequences of war. Confronting the overwhelming scale of death, she straddled the line between documentation and aesthetics, while mourning the dead. Hamilton eschewed showing bodies (as seen in Frederick Varley’s work) and the purely formal visualization of war with modernist aesthetics (as with David Milne’s art).

Many of Hamilton’s works depict cemeteries and often singular falling crosses, as depicted in “Battlefields from Vimy Ridge, Lens-Arras Road” [3] and “Gun Emplacements, Farbus Wood, Vimy Ridge,” [4] where gravity seems to drag the memorial and its associated memories toward oblivion. Other pieces include observers underscoring the ethical dimension of bearing witness to destruction and death without averting the gaze.

“Yes, it was like living in a graveyard.”

[Mary Riter Hamilton/LAC]

[Mary Riter Hamilton/LAC]

In her painting “Sugar Refinery at Écurie,” [5] Hamilton integrates her own presence as a self-aware observer into the narrative, where a new grave emerges in her immediate surroundings, close to her own hut. Employing the photographic shadow technique reminiscent of a snapshot, her silhouette subtly occupies the canvas’s left periphery—her arm casting bold strokes of paint with a palette knife. The vivid custard-yellow grave and the commanding upright cross on the right, compel viewer’s engagement, establishing a disconcerting proximity. In this artwork, Hamilton depicted the unsettling nature of her encounter, spanning the realms of the living and the dead, resonating with her retrospective reflection: “Yes, it was like living in a graveyard.”

At the Somme, [6] where she occasionally overnighted in pillboxes, she painted the desolation on cardboard and on wood reclaimed from hospital screens. She painted small, intimate scenes that ask the viewer to step close.

[Mary Riter Hamilton/LAC (3)]

[Margaret Janet Hart Collection]

In contrast, in more populated areas such as the towns of Arras, France, and Ypres, Belgium, [7] Hamilton centred her attention on themes of reconstruction, a pivotal facet of her oeuvre. These works—often depicting widows with their children at marketplaces—highlight the resilience of survivors.

Conversely, one of her late works, “Clearing the Battlefields in Flanders,” [8] documents a group of uniformed labourers filing along a path that trails to the left. They carry lit torches to clear the fields by burning tree debris, breathing the toxic fumes. They are diminished by the decimation and the uncanny darkness of the scene. Hamilton’s signature is a visual reminder that she herself lived in the bottomless pit. [9]

Hamilton’s signature is a visual reminder that she herself lived in the bottomless pit.

The risks she undertook had enduring consequences, manifesting as symptoms now recognized as post-traumatic stress, albeit without an official diagnosis of shell shock. A mental breakdown terminated her expedition in late 1921. A photo shows her looking aged and emaciated [10].

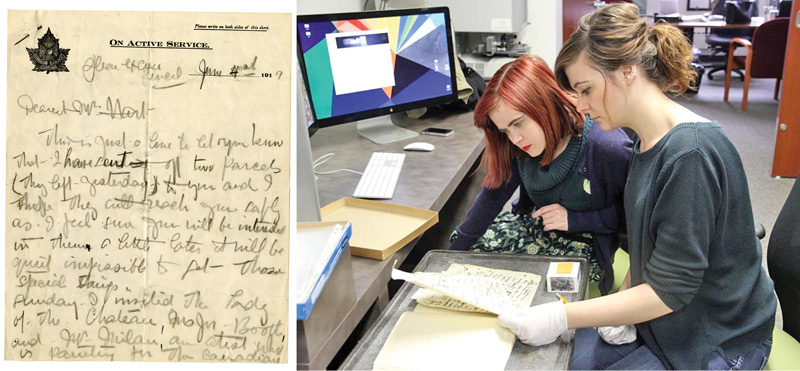

[MLC Research Centre Archive]

[Toronto]

[Toronto]

This article is based on research conducted for Gammel’s book, I Can Only Paint: The Story of Battlefield Artist Mary Riter Hamilton. [McGill-Queen’s University Press ]

Although she enjoyed remarkable international success—exhibiting her battlefield work at the Paris Opera House and receiving the Ordre des Palmes académiques from the French government in 1922, and the gold medal for her hand-painted batik scarves at the prestigious International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris in 1925—her recognition in Canada was largely neglected despite donating 227 war paintings to Library and Archives Canada.

Given the magnitude of the collection and the gaps in her archive, telling Hamilton’s story presents a daunting task. The discovery of Hamilton’s battlefield letters to her patron Margaret Janet Hart, now preserved at the Modern Literature and Culture Research Centre at Toronto Metropolitan University [11], however, help fuse Hamilton’s voice with her paintings to tell the story of an exceptional woman and artist and her extraordinary expedition.

Advertisement