Flying veterans of one world war often served with distinction in the next

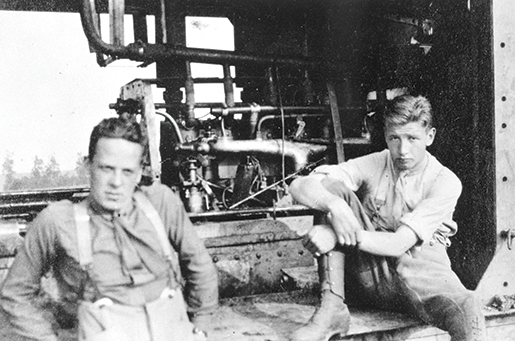

Canadians William Boger (left) and William Irwin were both flight commanders in No. 56 Squadron of the Royal Air Force in 1918. [LAC/PMR-73-192]

John Palmer became a barnstormer between the wars. [Courtesy of Hugh A. Halliday]

Palmer then served as an instructor in Britain and later in Canada; claims that he destroyed nine enemy aircraft are erroneous because he never flew in France. Late in 1918, he returned to Britain and flew briefly with the short-lived (and non-operational) Canadian Air Force. He returned to Canada in November 1919 and took his discharge.

But “Jock” Palmer never left flying. Based in Lethbridge, Alta., he became a well-known barnstormer, commercial pilot and instructor, with a two-year time out to establish and operate Radio Station CJOC. Although he was later hailed as the “Grandfather of Alberta Aviation,” Palmer had a tenuous career. He persisted through crashes, hard times and failed partnerships. In September 1939, he offered his services to the RCAF. By then he was operating a flying school in Cranbrook, B.C., with two de Havilland Moth aircraft, and, to date, he had flown 9,881 hours in 98 types of aircraft.

The air force took him on, first as a civilian instructor and then as a commissioned officer. Almost all his career was spent at No. 5 Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS) at High River, Alta., as instructor, chief flying instructor and commanding officer. He was routinely examined for his competence and always assessed in the highest terms—Voice: “Very Good”; Manner: “Experienced”; Ability to Impart Knowledge: “Exceptional”; Ability as Pilot: “Above average in all respects”; and General Ability: “An exceptional elementary instructor with an excellent background of experience.” He was recommended for an Air Force Cross in February 1943. When it did not go through, his superiors tried again, and an AFC was announced in October 1943.

No. 5 EFTS was a large school, with up to 82 training aircraft—de Havilland Tiger Moths and then Fairchild Cornells, which challenged Palmer’s girth. As the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP) began winding down in 1944, Palmer’s superiors tried to argue that his retention in the service was essential to the war effort, but he was released in September 1944, three months before the closing of No. 5 EFTS itself. When he retired from flying in 1955, he had accumulated some 18,000 flying hours; more than 1,000 of these at No. 5 EFTS. He was inducted into Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame in 1988. His medals are displayed in the Galt Museum & Archives in Lethbridge, while Palmer Road at the Calgary International Airport commemorates his name.

Irwin became commander of the No. 3 Service Flying Training School in Calgary, one of the largest schools in the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. [LAC/PMR-71-659]

Irwin was more senior to Burden for a few days, and he lorded that over him. When Burden got his first decoration, he pointedly reminded Irwin as to which of them was the “hero.” In fact, there were plenty of honours for both. Burden went on to win a Distinguished Service Order and a Distinguished Flying Cross; Irwin was awarded a DFC and Bar. Along the way, he destroyed 11 German aircraft in 76 patrols and 176 operational hours. Several flights involved low-level attacks on enemy airfields. (A full account of his career as a fighter pilot appears in the Fall 1981 edition of the Journal of the Canadian Aviation Historical Society.)

Wounded in an aerial ambush on Sept. 15, 1918, Irwin was sent to England to take an instructor course. On demobilization, he returned to Canada and became a schoolteacher and principal in Saskatchewan. When the Second World War broke out, he was anxious to serve but wanted to do something more than fly a desk. His old comrade, Hank Burden, had joined the RCAF and assured him that, given Irwin’s relative youth, a flying job could be obtained. Burden was as good as his word. The fact that Billy Bishop was Burden’s brother-in-law may have helped.

Irwin formally enlisted on July 9, 1940, took a flying instructor course at Trenton, then was assigned to No. 11 Service Flying Training School (SFTS) in Yorkton, Sask. He was brilliant and was advanced to chief flying instructor. On Jan. 10, 1943, he was given command of the school, and on May 14, 1943, he took over No. 3 Service Flying Training School in Calgary. This was one of the largest schools in the BCATP. Under his direction, No. 3 SFTS was repeatedly awarded the Air Minister’s Efficiency Pennant. On Jan. 1, 1944, he was made a Member, Order of the British Empire, and in March 1944, he was promoted to group captain.

Irwin retired from the RCAF in July 1945, but he did not return to teaching. Instead, he joined the federal Department of Transport. In 1959, he was appointed to the Canadian Transport Board (later the Board of Transport Commissioners). He died in Ottawa in January 1969.

George Fuller helped found the International Civil Aviation Organization. [Courtesy of Hugh A. Halliday]

On Sept. 10, 1917, he reported to No. 9 Squadron in France. His status as an observer was still considered “provisional.” Squadron and brigade officers examined him in knowledge of artillery co-operation, Morse code, operation of an aerial camera and skill with a Lewis machine gun. Thereafter, he would fight his war from the rear cockpit of a Royal Aircraft Factory R.E.8 two-seater reconnaissance and bomber biplane. “My seat was similar to an upholstered piano stool which could be rotated in a full circle,” he said.

Although he was “flying a desk,” Fuller had his hands full with delicate problems, including Flight Lieutenant George “Buzz” Beurling.

By March 1918, Lieutenant Fuller had logged 185 hours in 78 flights involving artillery spotting (particularly counter-battery work against enemy guns), photography and bombing. His commander wrote, “This officer has done excellent work as an Observer and has shown great reliability and keenness.” Following his tour in France, he took technical courses, then salvaged and repaired aircraft. He was discharged in April 1919 and returned to Canada.

Fuller spent the interwar years managing a fruit and vegetable company in Sherbrooke, while attending aviation events around Montreal that included the 1930 visit of the R-100 airship. When the Second World War started, he enlisted in the Administrative Branch of the RCAF. A course at Trenton, Ont., taught him Service Writing Style, Air Force Law, Central Registry and Orderly Room Procedure, and the administration of messes, canteens and equipment stocks. He went on to serve at McGill University, administering RCAF trainees, including radar personnel, and then at the headquarters of No. 3 Training Command in Montreal. In June 1945, he was appointed a Member, Order of the British Empire.

Although he was “flying a desk,” eventually in the rank of squadron leader, Fuller had his hands full with delicate problems, including Flight Lieutenant George “Buzz” Beurling, who flouted authority with the certainty that he was an untouchable hero. Beurling was eventually released early amid fanfare that he was being given a “head start” in a return to civilian life. RCAF headquarters sighed with relief. The hero promptly applied to join the United States Army Air Forces, which recognized a hot potato and ignored him.

Fuller made substantive contributions to aviation elsewhere. In the summer of 1945, the United Nations and its component agencies were being organized. The Provisional International Civil Aviation Organization (PICAO), headed by Air Chief Marshal Sir Frederick Bowhill, lacked a secretariat. The RCAF loaned him eight men and women, including Fuller. On Aug. 31, 1945, Bowhill wrote to Air Marshal Robert Leckie, RCAF Chief of the Air Staff, to express his thanks. “The work that they have done on the Preparatory Committee and during this first session has been outstanding, and every Nation represented has been loud in their praise. We were indeed fortunate in having such a wonderful team to lay the foundations for this important conference.”

Fuller was released from the RCAF in September 1945. Having helped to found the International Civil Aviation Organization (successor to PICAO), he went on to serve as an administrator with that body. Bilingual and diplomatic, he was especially good at securing the co-operation of city departments, foreign delegates and staff. Meanwhile, he kept in touch with veterans and serving personnel of No. 9 Squadron. He was thrilled when a 1981 visit to Trenton coincided with a Vulcan jet bomber of that squadron passing through, en route to a museum in California. It was a lot more airplane than the R.E.8 had been!

Advertisement