Betsy Doyle transfers hot shot to the guns of Fort Niagara during the bombardment of Fort George. [Alamy/2BACATE]

Some were heroines, some were victims, but most women simply endured and survived the War of 1812

After the Battle of Queenston Heights in October 1812, two women anxiously awaited word from the field of the carnage. Had their husbands been injured? Had they even survived?

One of the women was American Betsy Doyle, whose husband Andrew was a Canadian-born U.S. artillery officer. The other was American-born Canadian Laura Secord.

Both went on to be considered national heroines in their respective countries, though only long after their feats of courage.

Much has been written about the exploits of men during the War of 1812—of their heroism, victories and defeats—but not so much has been recorded about women.

History is written, as they say, by the victors—and historically, victors are soldiers and historians, keeping records of manly deeds. There are few records of the experiences and deeds of women who contributed to the war effort.

But women on both sides of the conflict “participated by any means that they were permitted,” wrote Sherri Quirke Bolcevic in Rhetoric and Realities: Women, Gender, and War During the War of 1812 in the Great Lakes Region.

Most women contributed by doing double duty on the home front, filling the roles of husbands, brothers and fathers who were away fighting—while also shouldering their own duties at home.

Women who actively supported the military worked mainly behind the scenes as servants, particularly as nurses, laundresses and cooks.

But some women took on more dangerous roles, serving alongside the men in battle, as Doyle did, or acting as informants, as did Secord.

Doyle learned her husband Andrew had been captured by the British and was being sent to England to stand trial as a traitor because he had been born in Canada.

All efforts to gain his release were futile.

This steeled Doyle’s determination. She “remained in the fort and…insisted on filling his place and doing his duty against the enemy,” wrote Peter A. Porter in a report to New York state commissioners.

Doyle took an active role in an artillery battle on Nov. 21, 1812, between Fort Niagara, on the U.S. side of the Niagara River, and Fort George in Upper Canada.

The Americans mounted a cannon on the roof of the mess hall so they could fire hot shot into the interior of Fort George in the hopes of setting its wooden structures on fire.

“During the most tremendous cannonading I have ever seen she attended the six pounder on the old mess house with red hot shot,” wrote Lieutenant-Colonel George McFeely in his report.

Using tongs, Doyle picked up five-kilogram-plus cannonballs that had been heated in a fire, then carried them to the rooftop and deposited them in the cannon, “never quitting her post till the last gun had been discharged,” wrote Porter. (See “According to Doyle” on page 20.)

More artillery duels followed. In May 1813, Fort George was captured by the Americans, who billeted officers with local families. This provided the circumstances for Laura Secord to prove her mettle as well.

Laura Ingersoll was the daughter of an American Revolutionary War veteran who emigrated with his family to Canada in 1795. In 1797, Laura married James Secord, a merchant in Queenston, Upper Canada, near Niagara Falls.

James served as a sergeant in the 1st Regiment of Lincoln Militia. He was wounded in the arm and his leg was shattered in the battle of Queenston Heights. Unlike Doyle, Secord was able to bring her husband home to care for him.

“Cannon balls were flying around me in every direction,” she wrote in 1860. “[I] found that my husband had been wounded” and when she returned home, she found “my house plundered and property destroyed.”

Women on both sides of the war “participated by any means that they were permitted.”

A few weeks after the fall of Fort George, Secord overheard American officers discussing a raid on the British outpost at Beaver Dams some 20 kilometres away. The spot was held by about 50 men commanded by Lieutenant James FitzGibbon.

Since her husband was in no shape to travel, Secord herself undertook to warn FitzGibbon, travelling furtively and circuitously by foot more than 30 kilometres through swamps, fields and woods, through the day and into the night.

Near the end of her journey, she came upon an Indigenous camp.

“I went up to one of the chiefs, made him understand that I had great news for Captain FitzGibbon, and that he must let me pass,” she wrote. The chief guided her to the lieutenant and “FitzGibbon formed his plans accordingly.”

When U.S. Colonel Charles Boerstler and about 500 men approached Beaver Dams on June 24, an ambush by some 400 Indigenous warriors thinned the American ranks. FitzGibbon was later able to persuade them to surrender.

“Not a shot was fired by any but the Indians,” FitzGibbon reported. “They beat the American detachment into a state of terror and the only share I claim is taking advantage of a favourable moment to offer them protection from the tomahawk and scalping knife.” (See “Saving Lieutenant FitzGibbon” opposite.)

No mention was made of Secord’s part in the British victory in the Battle of Beaver Dams at the time, possibly because she was living behind enemy lines and would have been treated as a spy.

After the war, the Secords lived in poverty for a time, subsisting on James’ war pension until he secured a post as registrar of the Niagara Surrogate Court. After he died in 1841, Laura, who had raised seven children, was left in financial difficulties and her petitions for a pension were unsuccessful.

Secord was 85 before her exploits became widely known—thanks to a visit to Canada by the future King Edward VII. In 1860, Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, visited Canada and noticed her name among those of 1812 veterans. Secord wrote a memoir of her wartime service for him, describing her frightening journey.

“I returned home next day, exhausted and fatigued. I am now advanced in years, and when I look back I wonder how I could have gone through so much fatigue, with the fortitude to accomplish it.”

She and her husband “stood ever ready and willing to defend this Country against every invasion come what might,” she wrote. “The services which I performed were truly loyal and…no gain or hope of reward influenced me in doing what I did.”

After returning to England, Edward sent Secord 100 pounds, a tidy sum at the time.

A lesser-known Canadian heroine also showed her mettle during the violence as Fort George was taken by the Americans, and again when it was retaken by the British.

British and Canadian troops in Fort George were on the receiving end of hot cannon balls, musket and mortar fire in May 1813.

They saw, “walking calmly through the shower of iron hail…Mary Madden Henry with hot coffee and food, seemingly as unconcerned as if she were in her own small garden.

“Time and again she went and came back with more sustenance, apparently guarded by some unseen angel from the peril which menaced her every step,” wrote an unknown author of the time.

“Through the day until darkness brought respite she was caterer and nurse, the only woman in the company to bind the wounds of those maimed in the fight.”

The Americans took the fort and occupied it until December; before leaving, they torched the town of Newark (modern-day Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ont.), leaving about 400 women, children and the elderly without shelter in the depths of winter. Many died of exposure.

Henry, whose husband was a lighthouse keeper, was credited with saving many lives. She poured water on the roof of her own house, which survived the arson. Then she opened the doors of her home and the lighthouse, providing shelter, food and medical attention to the homeless.

After the war, the Loyal and Patriotic Society of Upper Canada recognized Henry’s courage with a 25-pound award—the maximum annual pay for a teacher.

Working women could only dream of such a salary during the war.

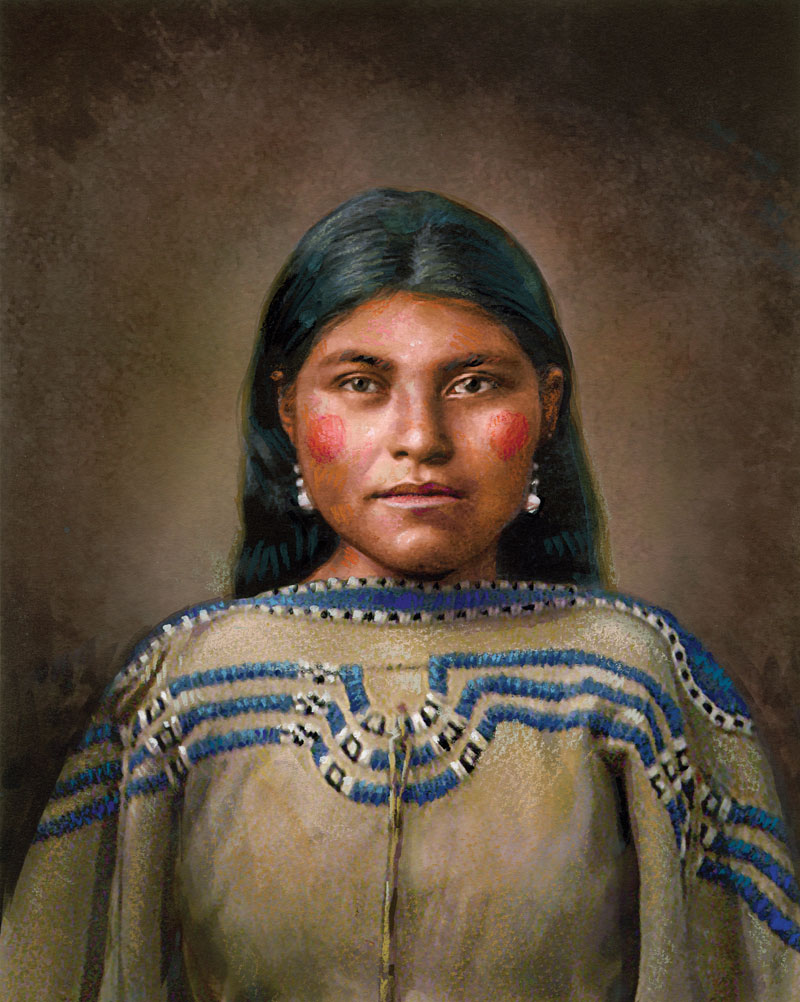

Tecumapese (above), sister of Indigenous leader Tecumseh, was influential in her own right. [Sharif Tarabay]

The average battalion in Canada was accompanied by 60 soldiers’ wives and about 100 children, noted Bolcevic. Theoretically, women were provided rations, transportation and lodgings, often sharing a cot with their husbands in overcrowded barracks.

“In actuality they worked to earn everything they were given,” wrote Bolcevic. They took on extra work for individual soldiers to supplement the meagre fare because women typically received only half of the rations a man received.

Women toiled cleaning barracks and hospitals, taking care of wounded soldiers and doing laundry, notably keeping mens’ uniforms clean.

Wives who followed their soldier husbands while they marched from place to place were called camp followers. They endured the same hardships as the men, “while having to continually prove themselves useful,” wrote Bolcevic.

They were not given protection during attacks, and were often wounded, killed or taken prisoner.

Indigenous women also followed their warrior husbands, but even less is known of their roles than those of settler women.

Indigenous women maintained family encampments, and also often worked for the military as laundresses, cooks and nurses.

Tecumapese, sister of the renowned Shawnee leader Tecumseh, was an influential female leader in her own right and was among the women who accompanied men on military campaigns.

Though paid as servants, Indigenous women may have also fought alongside their husbands, wrote Laurence M. Hauptman in a 2015 article in American Indian magazine.

Tecumseh’s confederacy, including the wives and children of its warriors, fought with the British army in 1813.

After Tecumseh died in battle at Moraviantown in Upper Canada in 1813, Tecumapese and more than 2,000 Indigenous women and children trekked 200 kilometres to Burlington Heights, near present-day Hamilton, Ont., to settle for the remainder of the war.

In 1814, Tecumapese was part of the delegation invited to meet with George Prevost, governor-in-chief of British North America, who was anxious that the British-Indigenous alliance continue.

Though it was considered bad luck to have women on a military ship, the wives of British naval officers sometimes joined their husbands aboard, a courtesy not extended to common sailors. Both the British and U.S. navies provided ration allowances to officers’ wives and children.

Those families also shared privations of life at sea and danger in battle.

“In September 1814, the wife of the steward of the British frigate HMS Confiance was killed by a roundshot as she tried to aid wounded men during the naval battle on Lake Champlain,” wrote Dianne Graves in In the Midst of Alarms: The Untold Story of Women and the War of 1812.

U.S. Commodore Stephen Decatur signed the wives of two crew members on as nurses.

Women played other roles, too, including that of informer.

Alicia Cockburn, whose husband Major Francis of the Canadian Fencibles, recognized the benefit of being perceived as the weaker sex.

She wrote to a cousin that she was considering travel to the U.S. under a flag of truce. “To do the Yankees justice they treat with uncommon civility [ladies] whom they allow to go much farther, and peep about much more, than we should do…whatever might be their beauty and accomplishments.”

And the British employed at least one woman as a spy.

In the summer of 1813, the British Commodore Thomas Hardy had three American warships, coincidentally under the command of Decatur, blockaded on a river near New London, Conn.

The British seemed to know about the Americans’ every move, thanks to a spy network established by British consul James Stewart, who was also prisoner agent and in an ideal position to collect helpful information.

Stewart was described by one historian as a charming type “displaying the manners of a courtier, the scruples of a highwayman and the social buoyancy of a cork.”

In July 1813, Stewart, who was suspected of spying, was forced to move inland. But he left behind his capable wife Elizabeth and their children.

“Mrs. Stewart took over his position as spy master, and she and her agents made New London the conduit for an almost endless stream of American intelligence reaching the entire [British] fleet,” wrote James Tertius de Kay.

In December, Decatur seized an opportunity to break out of the blockade. As the ships moved to the mouth of the river, a blue light was spotted on one side of the river; he called off the attempt when a second light was seen. The British had been forewarned.

No one could prove, but many suspected, that Elizabeth was behind the incident. After the war, James and Elizabeth went to Britain, where “a grateful Crown provided [Stewart] and his wife with a pension, chiefly in recognition of Mrs. Stewart’s outstanding espionage work during the war,” wrote de Kay.

The War of 1812 disrupted the lives of all women in Upper Canada, and forever changed it for those who lost husbands.

Female camp followers carry children, provisions and even an officer in this satirical etching published before the War of 1812. [Wikimedia]

Less well-connected women fought, too—to protect their homes, their families and communities.

Abigail Stone of Gananoque, south of present-day Ottawa, was shot in the hip while protecting her home during a raid in September 1812.

When U.S. forces occupied York in the spring of 1813, they torched the Parliament, looted houses and pillaged businesses.

Many residents fled, but not Elizabeth Selby Derenzy. Her father Prideaux Selby oversaw the provincial treasury, some 3,000 pounds.

Derenzy hid some of the money and put the rest into an iron chest, to which she added public documents.

She and Leah Allan, the mayor’s wife, dressed Selby’s chief clerk Billy Roe as “an old market woman, complete with sunbonnet and voluminous skirts” and sent him out of town with a horse-drawn wagon full of vegetables—and a chest of gold, wrote Pierre Berton in Flames Across the Border.

The War of 1812 disrupted the lives of all women in Upper Canada, and forever changed it for those who lost men in their lives. Meanwhile, the wives of soldiers or sailors who survived faced months and years of scraping to hold things together until the family was reunited. Wives and children of those who died could face penury.

Those in the path of the fight often encountered financial hardship or devastation. About a quarter of Upper Canadian families lost property due to the war, and about 10 per cent lost everything.

Many of the worst affected were new settlers. “In order to thrive…a frontier farm required at least two adults to complete all the arduous tasks involved in homesteading,” wrote historian George Sheppard in “Wants and Privations”: Women and the War of 1812 in Upper Canada.

Women usually cared for the family and tended the poultry, livestock and garden. Men cleared, plowed and harvested the land. Without men, it was difficult for a farm wife to keep a homestead thriving while her husband was serving. It was nearly impossible if he died.

During, and in the wake of, the war, many farms were auctioned off to pay creditors or to provide a widow funds to start a new life.

Troops on both sides of the conflict looted and burned towns and farmsteads, leaving families to start all over again.

For many women, simply surviving to more peaceful times was victory.

According to Doyle

Betsy Doyle served alongside the men at Fort Niagara from November 1812 until the Americans abandoned it at the end of 1813, even donning a uniform and taking a shift on sentry duty on the last night of the occupation.

After the fort fell, she fled on foot—in the depths of winter—with her four children to escape the British, arriving four months later at an army camp 500 kilometres away near Albany, N.Y. She continued to work as a nurse for the military, despite low and sporadic pay.

She never saw her husband Andrew again. He was released from prison in Britain in 1815 and returned to the U.S. Unable to find his family, he assumed they were dead. He remarried in 1819, the same year Betsy actually died.

At the time of her death, she hadn’t been paid for a year.

She died “by the want of those necessities which her pay would have procured,” Lieutenant Henry Smith wrote to the war department.

History was also unkind to Doyle. A book published in 1845 inaccurately recorded the Doyles’ names as Fanny and Tom, a mistake repeated on a monument to Doyle at Fort Niagara.

The historical record was corrected by research for the bicentennial of the War of 1812 by U.S. Niagara County historian Catherine Emerson and her staff.

Saving Lieutenant FitzGibbon

James FitzGibbon survived the War of 1812 thanks in part to timely interventions by women. [CWM/20020201-013]

Lieutenant James FitzGibbon might not have made it to the Battle of Beaver Dams but for the quick actions of an innkeeper’s wife.

On June 19, five days before the battle, FitzGibbon was chasing marauders when he entered the tavern at Deffield’s Inn, near Niagara Falls, to investigate the ownership of a horse tied up outside.

He was greeted by two Americans, one of whom was pointing a musket at him.

FitzGibbon extended his hand in greeting, then seized the gun’s barrel. In the ensuing scuffle the second man grabbed the lieutenant’s sword from its scabbard and prepared to cut short FitzGibbon’s career.

Mrs. Deffield, however, put down the baby she was holding, grabbed the wrist of the man holding the sword, wrested it away and hid it. Her husband arrived to help disarm the men and FitzGibbon took them captive.

Mrs. Deffield was subsequently lost to history—her first name went unrecorded.

Advertisement