A diver hovers over the wreck of Liberator 589D on Sept. 5, 2022, 79 years after it crashed into Gander Lake on takeoff, killing all four aboard. [Maxwel Hohn]

The B-24 aircraft of Young’s No. 10 Squadron made a slow turn and barrel-rolled into Gander Lake. No one survived. After a brief, aborted recovery effort, it was the last anyone saw of Liberator 589D for 79 years.

On Sept. 5, 2022, a team of veteran divers from Canada, the United States and France found the wreck lying upside down on a steep ledge nearly 50 metres below the surface, capping a nine-year quest by diver and researcher Tony Merkle.

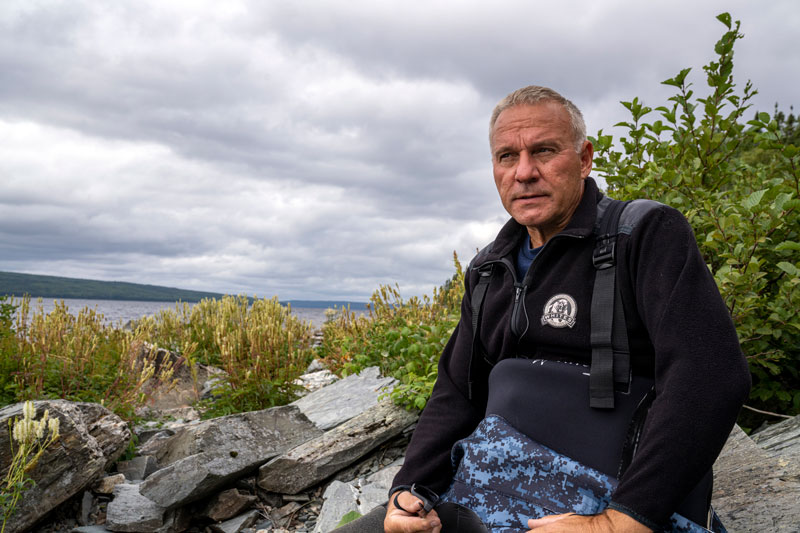

Tony Merkle spent nine years looking for the wreck of Liberator 589D. [Jill Heinerth/intotheplanet.com]

“I’ve never dived on a plane and since I discovered the site, it means a lot to me to share this part of Newfoundland history.”

Shortly after takeoff, the aircraft plunged into the deep, tannic waters of the narrow lake.

The crews of No. 10 Squadron were U-boat hunters. And good ones at that.

Flying British-supplied Westland Wapitis, Douglas Digbys and Consolidated B-24 Liberators, the sub hunters of No. 10 set an RCAF record, mounting 22 U-boat attacks during the war. They sank three: U-520 on Oct. 30, 1942; U-341 on Sept. 19, 1943; and U-420 on Oct. 26, 1943. Based at Gander since April 1943, No. 10 earned the nickname The North Atlantic Squadron.

On that fateful day in 1943, however, the crew of 589D were not U-boat hunting. Squadron Leader John Grant MacKenzie, an ear specialist from the air force medical unit in Toronto, was to test Liberator noise levels. He never got the chance.

Shortly after takeoff, the aircraft plunged into the deep, tannic waters of the narrow lake that snakes for some 50 kilometres a few hundred metres from the end of runway 27. It was suspected at the time that a foreign object, possibly a bird strike, had fouled the flight controls.

“I’m a lucky man,” a young medical officer was heard to say after the crash. “I was supposed to be aboard that aircraft!”

Squadron Leader John G. MacKenzie is buried in Gander Commonwealth Graves in Gander. The names of Wing Commander John M. Young, Flying Officer Victor E. Bill and Leading Aircraftman Gordon Ward are engraved on a plaque in St. Martin’s Cathedral, Gander. [Jill Heinerth/intotheplanet.com]

Recovery and salvage efforts were abandoned after 12 days due to poor visibility, extreme depth and cold water.

MacKenzie, a native of Lucknow, Ont., was buried in the Gander cemetery. The remains of Young of Toronto, Flying Officer Victor E. Bill of Winnipeg and Leading Aircraftman Gordon Ward of Toronto were never recovered.

“It is not an easy dive. The water is cold and perpetually a blood-red color from tannins in the lake. Our mission was to try to find a verifying mark that could prove the identity of the wreck.”

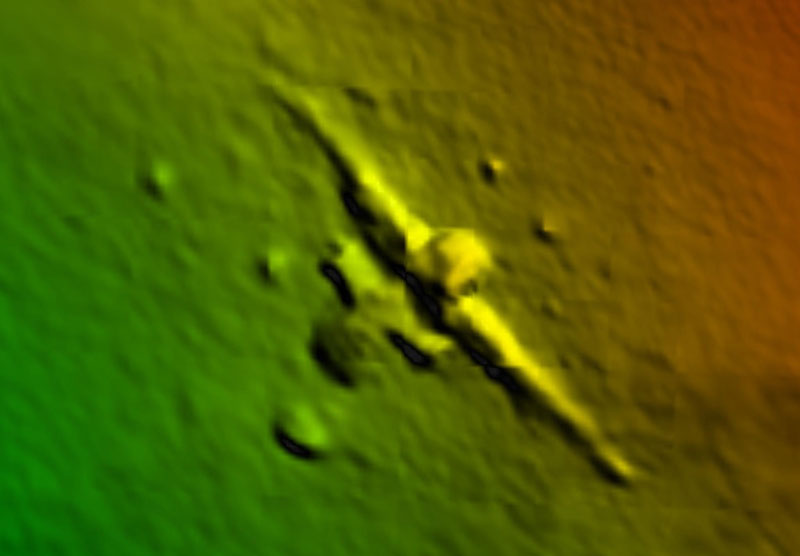

Nearly eight decades later in July 2022, Kirk Regular of the Shipwreck Preservation Society was mapping parts of the lake bottom for Memorial University’s School of Ocean Technology when, working off original crash report data, he recorded the plane’s exact location using multibeam sonar. He made 3D images of the wreck.

Kirk Regular’s 3D sonar scan from July 2022. [Sonar: Newfoundland & Labrador Shipwreck Preservation Society]

“There is always a bit of nervousness around a dive of this nature,” said diver Jill Heinerth, an RCGS explorer-in-residence, in an email interview with Legion Magazine. “The safety of our team is always in the front of my mind.

“It is not an easy dive. The water is cold and perpetually a blood-red color from tannins in the lake. Our mission was to try to find a verifying mark that could prove the identity of the wreck.”

Even with 30,000 lumens of light, Heinerth’s partner was unable to see her less than a metre away. A lumen is equal to about the light produced by one birthday candle a foot away. A 60-watt bulb emits around 750-850 lumens.

The Liberator’s landing gear stands out nearly 50 metres below the surface of Gander Lake.

[Jill Heinerth/intotheplanet.com]

“The dive was extremely challenging,” he said. “The tannic water reduced visibility to just 3 feet—swallowing any bit of light that we could throw at it. It was like descending into oil and very disorientating, which made it extremely difficult to film in 120-160 feet [37-48m] of water.”

The divers had less than an hour total run time so had to keep the logistics of the dive as simple as possible. They found the aircraft upside down on a precarious ledge. The next drop is more than 250 metres to the lake bottom.

“It is in a great state of preservation, but it is quite crumpled from the crash and early efforts to grapple the wreck for recovery,” said Heinerth.

[Heinerth] lost more than 100 friends to diving accidents, the bulk of them while exploring shipwrecks, and she is acutely aware of the risks inherent to her profession.

The Consolidated B-24 Liberator was among the most versatile heavy bombers of the war, famous for operations as diverse as U-boat hunting in the North Atlantic, where their introduction closed the mid-ocean gap in air cover, to the daring August 1943 low-level raid on the German-held oil refineries at Ploiești, Romania.

No. 10 Squadron lost seven aircraft and 24 aircrew in action; 27 more were lost in operational accidents, including the crash of 589D.

RCAF markings, instrumentation and other details confirmed that the hulk found perched on the edge of an underwater cliff was 589D.

Images and video from the dive are being donated to the Shipwreck Preservation Society of Newfoundland and Labrador for future educational outreach.

The effort to locate the bomber was part of a broader RCGS project, dubbed “The Great Island Expedition.” The divers are hitting various locations across the island, including off Gros Morne National Park on the west coast of Newfoundland and in Conception Bay along the east coast, where several ships were sunk by U-boats in the fall of 1942.

The portside light looks as good as new on the wing of Liberator 589D. [Jill Heinerth/intotheplanet.com]

“The two wrecks were difficult to reach, but we have successfully gathered a lot of images and video to tell the story of their sinking and the heroism of rescuers in St. Lawrence and Lawn, Nfld.,” said Heinerth.

A native of Mississauga, Ont., Heinerth is a renowned author, marine photographer and veteran of more than 7,800 dives into undersea caves and on wrecks worldwide. She’s lost more than 100 friends to diving accidents, the bulk of them while exploring shipwrecks, and she is acutely aware of the risks inherent to her profession.

“I am incredibly proud of our team for completing six safe dives on the [aircraft] site and getting the images needed for confirmation,” she said.

Advertisement