Wounded while fighting off an attack on his observation post, Gorden Boivin eventually beat back his physical and psychological demons

Story and photography by Stephen J. Thorne

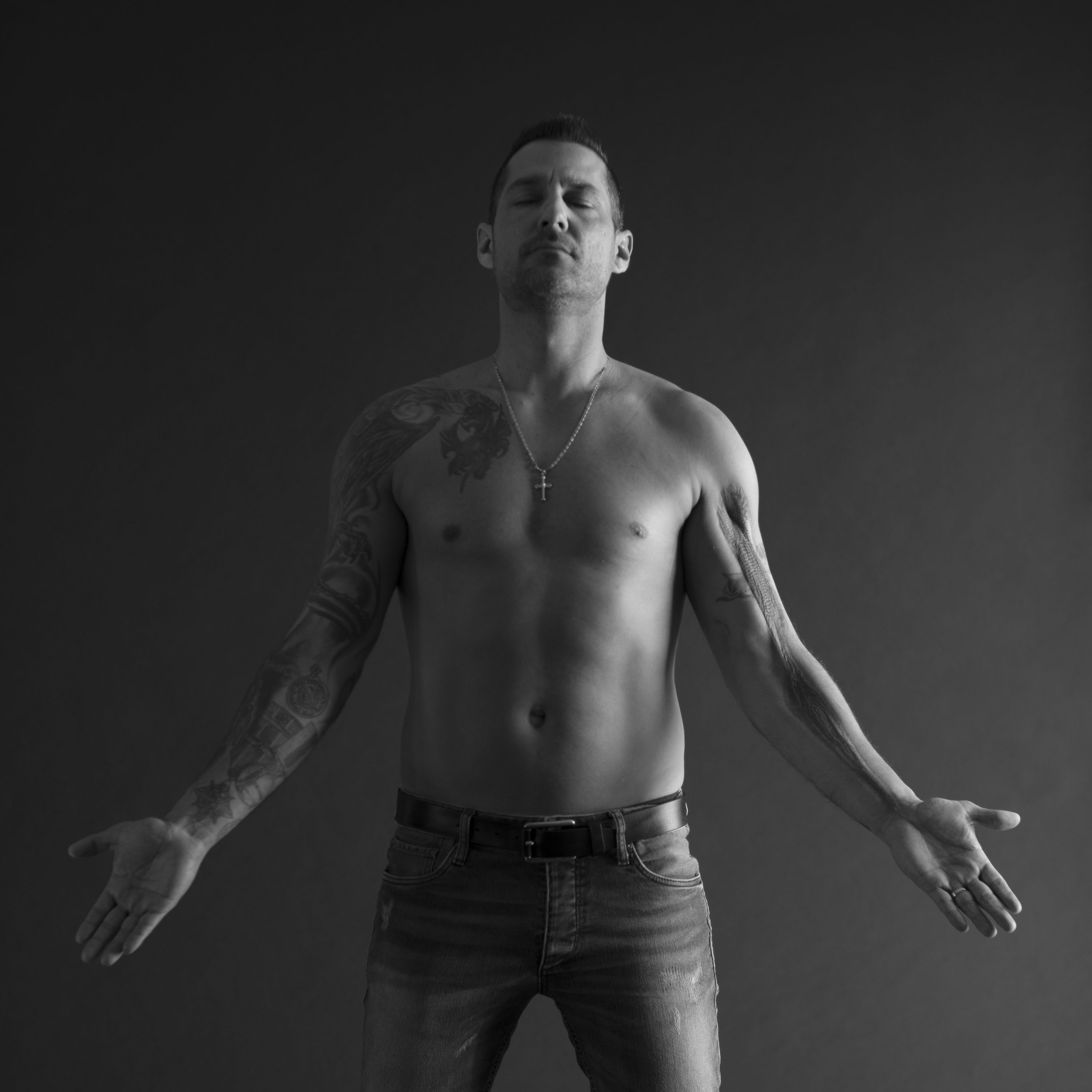

From darkness, there is light. Corporal Gorden Boivin knows this only too well.

Boivin’s descent into darkness began with a firefight at Checkpoint 3 in Panjwaii District, at the very perimeter of Canadian operations in Afghanistan.

It was Nov. 22, 2007, and Boivin, of Sorel, Que., was a radioman with the Royal 22nd Regiment, the vaunted Vandoos. There were 24 of them stationed at the last checkpoint west of the last forward operating base, west of Kandahar.

They were surrounded by enemy 24/7. Their area of operations was so hot the helicopters wouldn’t come. There was only one road in and out, and it was usually mined.

“We were at the edge of the occupation area,” recalls Boivin. “There was nothing after us. It was crazy all the time.”

Boivin had survived an explosion two weeks previous when the enemy detonated a bomb too soon, lifting his vehicle off the road, but hurting no one inside.

Now he and Sergeant Martin Marcil were manning an observation post when the usual prayer echoing from the speakers at the local mosque ended with what Boivin later interpreted as a call to arms.

“At the end of the prayer, they didn’t say ‘Allah Akbar’ like they usually did. Instead, it was: ‘Allah! Allah! Allah!’ Over and over and over again, like 10 times. I turned to my buddy and said: ‘What the fuck’s with him?’ Then they started shooting.”

Boivin went to the .50-calibre machine gun that was mounted on one side of the observation post, but the main thrust of the attack was coming from the other side. Rocket-propelled grenades were hitting the sand-filled walls that sheltered them.

It was a desperate defence. They were surrounded and outnumbered, with no prospect of immediate reinforcement.

Boivin wheeled around, stepped toward the back of the post, put his left hand on a corner post for support, and leaned over to pick up an M72 light anti-tank weapon that was propped against the wall. The M72 has been a staple of the U.S. army since the early days of Vietnam. Without the heavy machine gun, it was the next best option in his arsenal. But Boivin never got to use it that day.

Just as he leaned, an RPG hit the post and exploded, the second one in 30 seconds. It blew up an arm’s length away. Boivin flew backward into the middle of the post.

Marcil, his sergeant, was peppered in the back with more than 100 pieces of shrapnel. (He would do time in the field hospital in Kandahar and return to action within weeks.)

Boivin’s left arm was ripped open and almost entirely de-gloved (the flesh stripped from the bone) from his shoulder to his wrist. His chest, face, hands, arms and legs were cut, burned and showered with shrapnel. A piece smaller than a baby’s fingernail stopped two millimetres from his heart and certain death. Another penetrated his throat in the hollow just above his collarbone. He was bleeding out from a severed artery. Nerves were damaged. Shock was setting in.

The remaining soldiers repulsed the attack. It was an hour before they were evacuated by helicopter. It was the longest hour of Boivin’s life, and probably the lives of many of his comrades in arms who fought so desperately.

Boivin remembers feeling cold as he was transfused with refrigerated blood in the Kandahar hospital. Doctors would eventually reconstruct his arm, grafting skin from his leg. His worst physical injuries, however, were the deceptively small holes in his throat and chest—like bullet wounds, except they were jagged pieces of shrapnel, at least 10 of which couldn’t be removed. As a result, Boivin is a walking security alarm.

“I am lucky to be alive,” he says.

Continued from Military Health Matters e-report No. 12

He recovered from his physical injuries. But for years after, he battled psychological wounds like those responsible for the unknown number of military suicides that have occurred since Canada joined the fight against terrorism in 2001.

After the hospitals, after the rehabilitation, after his most significant steps toward physical recovery, Boivin returned to daily life a depleted man, struggling to overcome post-traumatic stress disorder and addictions to drugs and alcohol.

Some of his experiences prior to his last firefight blew his illusions about service, discipline and what it meant to be a soldier.

He questioned everything he had believed and signed on to. He questioned Canada’s role in Afghanistan, its commitment and its lack of progress. He didn’t trust the decision-making on which lives depended. He didn’t trust Afghans he fought beside. Friends died, for what? Nothing made any sense any more.

He knew he was in trouble. And while some soldiers have complained about access to services, Boivin says the military provided outstanding support.

“I have everything I want to go forward. Looking back, it was tough to admit I needed help. It was tough to say ‘I need help. I am broken.’ That part is difficult to do, but once you do it, they were there for me.”

He has no illusions about where he was and how far he’s come.

“I was really, really, really crazy,” he says. “When my treatment ended, my psychiatrist said, ‘Gorden, I was scared for you when you arrived; I thought maybe this guy won’t come back.’ But we worked really, really hard.

“I did therapy; I took medication; I did a lot of meetings. I took it really seriously.”

He calls his physical and psychological wounds his “two big ills.”

“The physical thing was not fun at all. But while I was fighting to recover physically, my head was OK because I was focused. It was after I recovered from my wounds that I [spiralled]. I cannot say which was harder, one or the other. The psychological is more complicated to treat.”

He marked seven years clean and sober on April 15. He feels better. He has skills and coping mechanisms—he calls them “tricks”—to deal with his PTSD. Before, he was a boxer. Now he’s a salsa dancer. He has a good woman and two chihuahuas in his life. He counsels prisoners and brings food to the elderly. “I’ve changed,” he says.

He is a new father with a new purpose. His son Alex, all eight pounds, 10 ounces of him, was born this spring, on the anniversary of the day Boivin quit alcohol and drugs.

He is wearing the Canadian flag again, this time as a stationary rower at the Invictus Games in Toronto in September.

He has come through triumphs big and small, and now he will be competing alongside athletes who have faced down the same ills and the same demons.

“I will wear the Canadian flag for a healthy and positive event,” he says. “It is kind of my occasion to be proud again to wear the flag, to be a Canadian.

“I was on the dark side. It is my time to feel that I am back.”

To view more images and read other instalments in Stephen J. Thorne’s Portrait of Inspiration project for Legion Magazine, please click below.

Advertisement