How a terror group rooted in ancient texts and prophesies

used the apocalyptic properties of water in its global war.

Kurdish Peshmerga forces occupy Mosul Dam in northern Iraq on Aug. 19, 2014, after joining Iraqi special forces in defeating Islamic State fighters. IS had control over the potentially devastating power of the dam for a few anxious days. [Lynsey Addario/Getty Images/653005836]

The Islamic State brought a multitude of weapons to bear in its crusade to create a global caliphate, but few raised more concern than its control over water. Using the Internet, imagery and word power, in addition to guns, blades and bombs, the group variously known as IS, ISIS and Daesh instilled fear and terror from Iraq and Syria to Turkey, Africa, Europe and beyond.

ISIS strategists have been resourceful. While twisting Koranic verse to their own ends, they exploited every means possible to further their cause, adapting technology, mastering mass communication and recruitment, seizing and rerouting weapons supplies, and exacting barbaric medieval vengeance on their enemies, including drowning caged prisoners in a captured swimming pool. ISIS developed chemical weapons at Mosul University, one of the largest schools in the Middle East, tested lethal compounds on prisoners, and used chlorine gas against Syrian troops.

In addition to this multipronged and high-tech strategy, however, ISIS also relied on an age-old weapon to particular advantage in its war of terror: water.

Water has been a virtual constant in the ISIS arsenal, just as it has been throughout the region for thousands of years, dating to the Mesopotamian and Babylonian empires.

By mid-2016, ISIS controlled six of eight large dams on the mighty Euphrates and Tigris rivers and was continuously attacking a seventh. It was, in turn, taking these sources of green energy and using them as weapons of war.

“On one hand, IS is damming the river to retain water and dry up certain regions, thereby cutting off the water supply to villages and communities,” Tobias von Lossow, a conflict researcher at the Institute for International and Security Affairs in Berlin, told the German radio network Deutsche Welle. “On the other hand, it has also flooded areas to drive away their inhabitants and to destroy their livelihoods.”

ISIS controlled Syria’s largest dam, the Tabqa on the Euphrates, for almost three years. They wired it to blow and used it as a secure base of operations, sheltering commanders and high-value prisoners alike within its walls in the belief that coalition aircraft wouldn’t bomb its 70-metre-tall, five-kilometre-long barrier for fear of wiping out the city of Raqqa, just 40 kilometres downstream.

American bombs did damage the dam’s entrance, however, raising UN concerns that further harm could lead to “massive-scale flooding across Ar-Raqqa and as far away as Deir-ez-Zour,” one of Syria’s largest cities. A breach, it reported, “would have catastrophic humanitarian implications in all areas downstream.”

United States-backed forces captured the dam in May 2017 after striking a deal with some 70 ISIS occupiers, who dismantled bombs and booby traps, surrendered heavy weaponry and ordered the withdrawal of surviving forces from the city.

Foreign Policy magazine once described Iraq’s hydroelectric facilities as “a soft underbelly in the fight against ISIS.” Some officials have categorized the destructive power of ISIS-held dams as “Biblical.” It seems fitting, then, that a terror group whose goals, ideologies and modus operandi are rooted in old texts and prophesies would resort to such apocalyptic methods.

“Water always goes where it wants to go,” Margaret Atwood wrote in The Penelopiad, “and nothing in the end can stand against it.”

Water has endured through the ages as one of nature’s ultimate weapons. Like all of nature’s elements, however, humans wield water at their peril because, once unleashed, it is all but unstoppable.

Water can destroy, defeat and subjugate; defend, delay and deny. Lack of it can starve and thirst entire populations. Too much of it can isolate armies and citizens, spread disease, destroy crops, render rich soil infertile, and flatten entire cities. Most of us associate water with life and purity, but the destructive power of H2O can be insidious or devastatingly sudden.

“Water is fluid, soft and yielding,” wrote the sixth-century Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu. “But water will wear away rock, which is rigid and cannot yield. As a rule, whatever is fluid, soft and yielding will overcome whatever is rigid and hard. This is another paradox: what is soft is strong.”

And how.

A cubic metre of water weighs a metric tonne, or 1,000 kilograms. For a few anxious days in 2014, ISIS controlled the already-unstable Mosul Dam in Iraq, the country’s largest, with a reservoir capacity of more than 11 billion cubic metres.

Built in 1984 and long known as the Saddam Dam, it controls the flow of the Tigris River north of Mosul, supplying electricity to more than a million people. Its destructive potential is conceivably many times that of the 15-kiloton atomic bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, in 1945.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers estimated at the time of the ISIS occupation that, if ruptured, Mosul Dam’s floodwaters would deluge more than 300 kilometres downstream. Waves as high as 25 metres would swallow villages and much of the city of Mosul, which has a population of more than 600,000. The flooding would likely reach Baghdad, it said, causing up to US$20 billion in damage and potentially killing and displacing millions of people.

Water as a weapon of war and punishment dates from antiquity and is woven throughout myth and legend. This was particularly true in the region known as the cradle of civilization, the heart of the ISIS area of operations.

It is here, in Mesopotamia—the land between two rivers—where the Tigris and Euphrates stretch hundreds of kilometres and are the lifeblood of the fertile crescent. For more than 6,000 years, they were the primary sources of life-sustaining silt, nutrients and irrigation, the superhighways of an age, and the focal points of conflict.

It is not surprising, then, that water figured heavily in the region’s chronicle and lore—stories that would reappear in cultural narratives through history and across civilizations, often depicting its vast power as a weapon wielded by gods.

In the biblical narrative of the Exodus, Moses raises his staff and Jehovah brings the waters of the Red Sea back down on the Egyptian Pharaoh’s army, allowing the Jews to escape from Egypt. Use of water as a weapon dates from ancient history and lore. [iStock]

In another version of what reads like the same story, the Bible relates how God flooded “the world of the ungodly,” sparing Noah, his family, and selected animals.

Later, Jehovah parted the Red Sea so that Moses could lead the Jews out of Egypt. Then He closed it again and wiped out the pursuing armies of the Pharaoh in a torrent.

Some of the earliest water wars took place right in the Islamic State’s backyard, fought by the same peoples who brought the world agriculture, religious rites and the wheel. In the first recorded wars, between 2700 and 2400 BC, Mesopotamian city-states clashed over fertile soil, irrigation systems and water diversion, using the latter against each other.

In 1792 BC, it was conflict over water that inspired King Hammurabi of Babylon to create the Code of Hammurabi, among the first comprehensive legal codes in human history. Many of its 282 edicts governed the use and misuse of water and irrigation systems.

In the 700s BC, Assyrian King Sargon II kept the Armenian Haldians at bay by destroying their irrigation network. In 695 BC, Assyria’s King Sennacherib levelled Babylon to quell a rebellion, diverting an irrigation canal “so that water would wash over the ruins.” Later, seeking retribution for his murdered son, Sennacherib destroyed the city. “I destroyed, I devastated, I burned with fire,” he wrote. “I completely blotted it out with floods of water and made it like a meadow.” He sent Babylon’s dust as presents to “the most distant peoples.”

Subsequent rulers also used water as a strategic weapon, including King Assurbanipal, who seized Arabian wells. Cyrus the Great reputedly took a rebuilt Babylon in a single night in the sixth century BC by diverting the waters of the Euphrates, opening a surprise nighttime approach right up to the city walls.

Hulagu, destroyer of medieval Baghdad, used Tigris floodwaters to trap the caliph’s horsemen outside the city walls. In modern times, both combatants in the Iran-Iraq War of the 1980s used water to check advances in the southern marshlands. After the First Gulf War, Saddam Hussein drained the marshes to quell an insurgency.

Water has been a weapon everywhere, whether there is a lot or a little.

In a study published in the journal Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, Dutch researcher Adriaan de Kraker reported that about a third of floods in the southwestern Netherlands between 1500 and 2000 were deliberately caused during wartime, with limited success.

During the Eighty Years’ War (1568–1648), Dutch rebels led by William of Orange used the low-lying flood-prone landscape against a Spanish campaign in what is now northern Belgium and the southwestern Netherlands. In attempts to liberate Bruges, Ghent and Antwerp from Spanish dominance and defend territory, the rebels destroyed strategic seawalls, deliberately causing large-scale floods.

“The plan got completely out of hand,” wrote de Kraker, an assistant professor at VU University Amsterdam. “It came at the expense of the countryside of northern Flanders, now Zeeland Flanders, some two thirds of which was flooded.”

Some areas remained underwater for more than a century, leaving surviving buildings and roads coated in thick layers of clay and, since it was seawater, ruining agriculture.

The strategy “had a devastating impact on the landscape [and] completely missed its directly anticipated goals,” de Kraker reported. “Bruges, Ghent and Antwerp were subdued

by the Spanish…leaving the rebel side empty-handed.”

As a rule, strategic flooding is a high-risk tactic. “It can only be successful if there’s a well-thought-out backup plan and a plan for fast repairs,” de Kraker wrote.

No amount of planning will make flooding an effective weapon if the landscape isn’t right. The shape of the land and its makeup—the type of rock and soil, for example—will always dictate the extent and effectiveness of a strategy requiring a degree of control that often is not possible.

Too much water, and an enemy can resort to boats to transport men and equipment; too little, and it’s just a nuisance. Weather can influence the success or failure of what some historians have dubbed hydrologic warfare.

The Netherlands’ Hollandic Waterline, strategically flooded low country southeast of Amsterdam, failed to do its job when it froze in the winter of 1794-95, allowing French invaders an open route in.

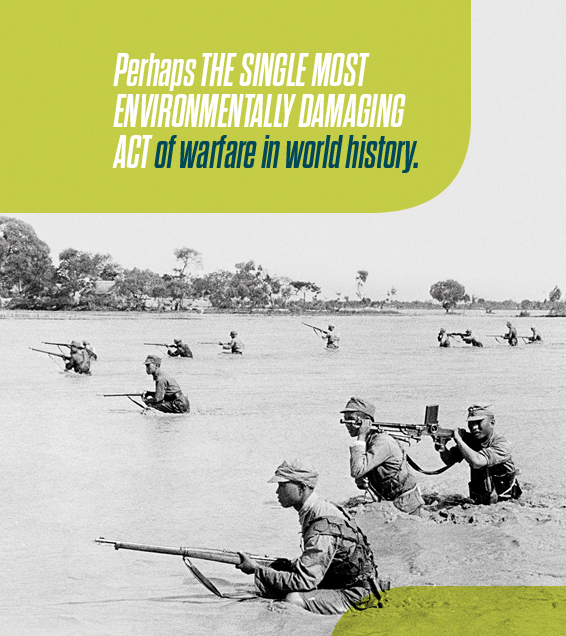

Efforts to stop an enemy force with water can even hinder or harm the ones it is supposed to benefit. In a desperate attempt to block Japan’s brutal advance during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937 to 1945), Chinese nationalist armies under Chiang Kai-shek breached the Yellow River’s dikes in Henan province in June 1938.

The move may have bought the nationalists time to withdraw and regroup, and it bogged down the Japanese in fields of mud for a while. But it only postponed Wuhan’s fall by a few months, reported historian Micah Muscolino, a tutor in late imperial and modern Chinese history at Oxford University’s Merton College.

For nine years, the floodwaters spread southeastward, affecting vast areas of three provinces, killing as many as 800,000 Chinese and displacing almost four million. In Henan’s Fugou county alone, more than 1,800 villages were flooded, covering more than 90 per cent of its total area. Japanese losses were negligible.

Chinese troops advance through enemy fire amid floodwaters of the Yellow River, circa 1938. The decision to combat the Japanese conquest of China by breaching the river dikes proved disastrous, killing up to 800,000 Chinese and displacing almost four million—with little tangible benefit. [Getty Images/515163266]

The floodwaters flowed unimpeded, aided by a landscape that happened to have a generally higher elevation in the north.

“No topographical divisions prevented the [water] from moving southeast to join the Huai River,” Muscolino said. “Advancing at a steady rate of around 16 kilometres per day, floods spread into narrow, shallow beds of rivers and streams that flowed toward the Huai.” The floodwaters inundated fields. As they entered the Huai’s headwaters, they turned northeast, cutting a railway line, depositing millions of tonnes of silt and flooding a major lake. “Nature’s rhythms heightened the catastrophe, as high levels of summer precipitation increased the flooding’s severity. Especially heavy rains fell throughout June and July. Waters surged as a result.”

During the Second World War, both Allied and Axis powers used water as a weapon. In the Netherlands, the traditional water defences were ineffectual against the Nazis, who overran the country in just six days. The Germans flooded part of the defensive line north of Amsterdam to guard against a possible seaborne invasion that never came. Dutch claims for territorial compensation after the war were all but ignored.

A U.S. Army medic administers plasma to a wounded soldier in Sicily in 1943. Invading Allies were prepared for German biological warfare but the local populace wasn’t. A malaria epidemic ensued after a Nazi entomologist concluded that re-flooding a former marshland and stocking it with larvae would unleash a wave of malaria-carrying mosquitos. [United States National Archives/111-SC-178198]

Drawing on American archives and the diaries of Italian soldiers, Snowden wrote in his 2006 book The Conquest of Malaria in Italy that the scheme was orchestrated by Erich Martini, a medical entomologist, Nazi Party member and friend of SS commander Heinrich Himmler.

The Germans ensured there were no witnesses by ordering civilians to leave when they reversed the pumps that drained the marshes. They then introduced millions of larvae of a malaria-carrying mosquito.

Allied troops landing just south at Anzio were one step ahead, however. They’d been given anti-malarial drugs. Area residents suffered until 1950, when the marshes were drained again and the mosquitoes died out.

Under the sea, Germany’s Kriegsmarine used the cloak of water to nearly bring Britain to its knees, waging a devastatingly effective U-boat campaign to raid transatlantic convoys supplying the Allied war effort. A combination of new sonar technology and American reinforcement in 1942, along with Hitler’s dismissive attitude toward naval operations, ensured the campaign would ultimately fail, but only after some 175 Allied warships and nearly 3,500 merchant vessels were sunk at a cost of 72,200 sailors’ and merchant seamen’s lives. U-boat crews also paid a heavy price: 793 U-boats ended up on the ocean bottom and 28,000 of 40,000 German submariners died, a 70 per cent casualty rate.

Probably the best-known example of dam warfare took place on the night of May 16-17, 1943, when No. 617 Squadron of the Royal Air Force skip-bombed three dams in the Ruhr Valley, striking at the industrial heartland of Germany.

The plan—Operation Chastise—was to cause floods that would disrupt Nazi war production. But while innovative and heroic, the attack by a handful of low-flying Lancasters accomplished somewhat less than the strategists had hoped. Only two dams were breached.

Two power stations were destroyed and several more damaged, along with some mines and factories. But the impact was limited; Germany returned to full production within four months.

Subsequently dubbed the Dambusters, 133 aircrew—including 30 Canadians—took part. Fifty-three were killed—14 of them Canadians—and three were captured. About 600 Germans and 1,000 forced labourers, mainly Soviets, died in the flooding. British morale got a boost, but the war would continue for two more years.

The power of water as a weapon—and a cause—of war has not abated. To the contrary, Goldman Sachs has described water, namely freshwater, as “the petroleum of the next century,” assuring little will change for the better.

Some say water has been an obstacle to resolving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, citing Israel’s diversion of the Jordan River into the Negev Desert a half-century ago. The project has robbed the Dead Sea of a third of its surface area and turned the storied river to mud.

“All this has come at the expense of the Palestinians, who accuse Israel of manipulating water supply to suppress them,” Newsweek reported in 2015. “Some 85 per cent of all the water in the West Bank goes to Israel, according to some estimates. The Palestinian Water Authority says that Israelis consume seven times more water, per capita, than Palestinians: a spur, if ever there was one, for a resumption of the Intifada.”

Along the China-India border, a dispute simmers after China announced in 2016 it was diverting the Xiabuqu, a domestic river feeding into the trans-boundary Brahmaputra River, to facilitate construction of two hydroelectric dams. Last year, India’s Assam state was gripped by devastating floods, after which China refused to release hydrological data on its upstream operations.

“China’s refusal to cooperate over shared water resources shows it is willing to use water as a geopolitical weapon,” reports Global Risk Insights, which conducts political risk analysis.

A 2012 U.S. intelligence report assessed how water issues—some caused by climate change—would affect national security interests over the next 30 years. It said water shortages, quality issues and floods, when combined with poverty, social tensions, environmental degradation, ineffectual leadership and weak political institutions, contribute to social disruptions that can cause states to fail.

Depletion of groundwater supplies in some agricultural areas will pose a risk to both national and global food markets, it added, while water shortages and pollution will likely harm the economic performance of important trading partners.

“As water shortages become more acute beyond the next 10 years,” said the report, “water in shared basins will increasingly be used as leverage; the use of water as a weapon or to further terrorist objectives also will become more likely.”

Canadian Dambusters

Flight-Lieutenant Joseph McCarthy (fourth from left) was an American serving with the Royal Canadian Air Force. He and some 30 Canadians were among the 133 aircrew who launched Operation Chastise, the legendary “Dambusters” raid of May 16-17, 1943. [IWM/TR1128]

Among the 133 crew who departed England that night in 19 specially modified Lancaster bombers were 87 Britons, 30 Canadians, 13 Australians, two New Zealanders and an American—Flight-Lieutenant Joseph McCarthy, a pilot serving with the RCAF.

Two of the Canadians were pilots—Pilot Officer Vernon Byers of Star City, Sask., and Pilot Officer Lewis Burpee of Ottawa, neither of whom made it to their targets.

Flying in the second wave, Byers’ AJ-K (K-for-King) Lancaster was shot down by flak and plunged into the sea off the Dutch coast. Burpee’s AJ-S (S-for-Sugar) was shot down in the third wave over the Netherlands. Neither survived.

There were two Canadian flight engineers, five bomb-aimers and six navigators, including Harlo Taerum of Milo, Alta., who guided Wing Commander Guy Gibson’s aircraft to the Möhne Dam, where their bouncing bomb landed short of its target.

Two of the Canadian bomb-aimers hit pay dirt, with one of them—Vincent MacCausland of Charlottetown—the first to breach the Möhne Dam.

MacCausland did not survive the mission. After accompanying the subsequent raid on the Eder Dam, his Lanc was shot down crossing the Dutch coast and crashed into the sea.

One of the mission’s three captured crew members was Canadian: Flight-Sergeant John Fraser, a bomb-aimer from British Columbia, eluded his captors for 10 days after bailing out of his burning plane at the Möhne Dam. He walked 300 kilometres, surviving on turnips and potatoes from farmers’ fields. He was caught 50 kilometres from the Dutch border.

Advertisement