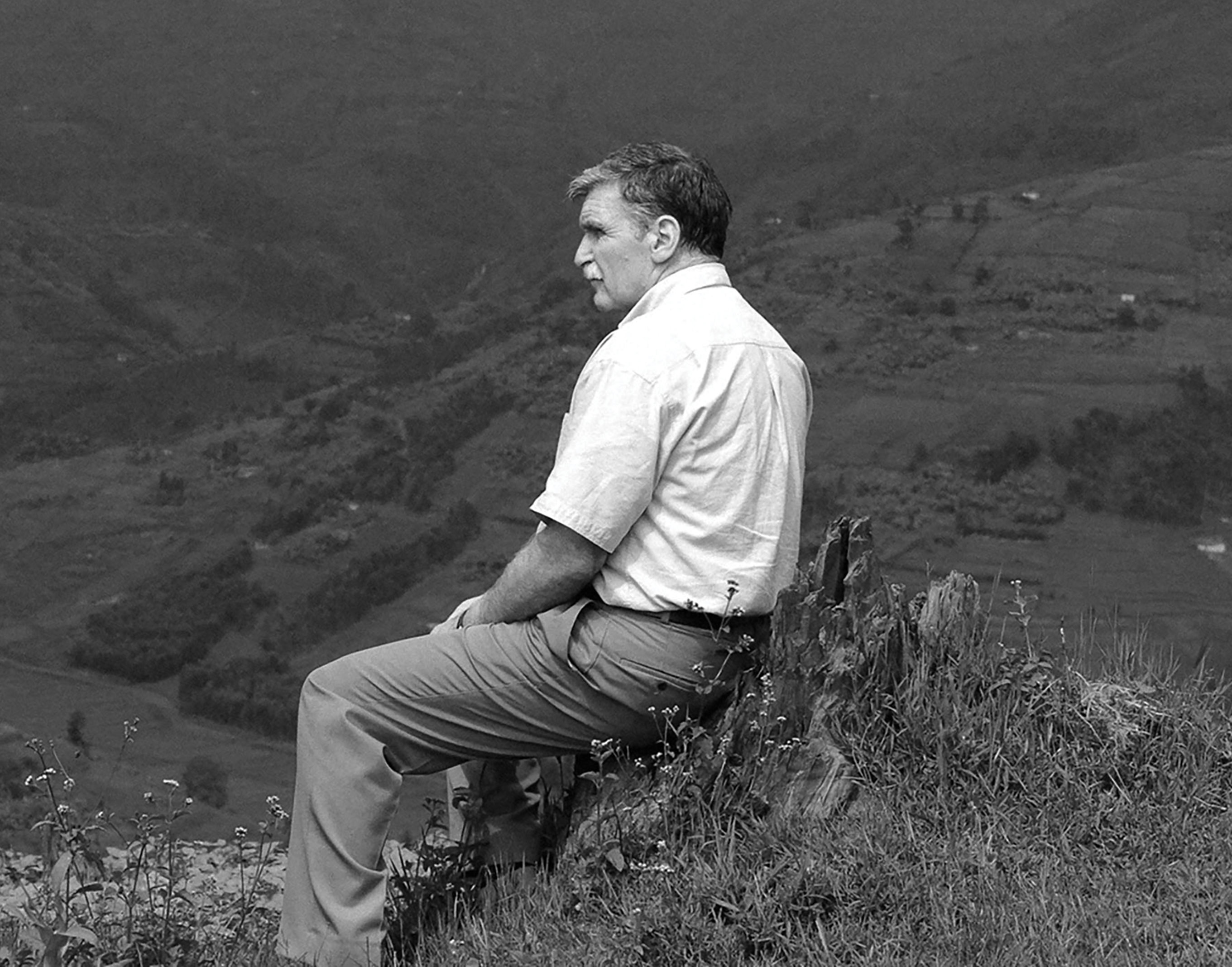

[Peter Bregg]

I too was a commander who set out on what I thought was an exciting adventure,” Romeo Dallaire writes in Waiting for First Light: My Ongoing Battle with PTSD, “only to bear witness to the most terrible horrors on earth.”

It is a familiar story, one first heard in modern times in the Boer War, and given full flower in the slaughter of the First World War. A soldier goes to a foreign land with a sense of duty and adventure and finds himself in a hell he was unable to imagine.

The exciting adventure for Dallaire was a peacekeeping mission in Rwanda in 1994, where 800,000 people were eventually slaughtered. He described this in Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda. What he didn’t describe was the effect it had on him.

“PTSD,” he writes in his new book, “which was known in the past as ‘shell shock,’ ‘battle fatigue,’ ‘combat stress reaction,’ and even derogatory names such as ‘malingering,’ destroyed the person I was.” He became two men in the wake of his injury—the outward man who remained duty-bound and functioning, and another man inside, who still lived on the battlefield.

Dallaire’s account is one of the most detailed and harrowing, and certainly the highest ranking, stories of PTSD. When he left Rwanda, he took its horrors with him. He had witnessed the ravaging of a nation—rape, mutilation, murder, starvation, hundreds of thousands of corpses left to rot. But he also witnessed bureaucratic ineptitude, the heartbreaking indifference of the United Nations’ leadership, and global neglect in the wake of genocide. He was scarred not just by the slaughter, but by the disturbing knowledge that it could have been prevented.

When he returned to Canada and domestic life—choosing a new sofa pattern, ensuring his children ate their vegetables, mowing the lawn—the transition was onerous. Compared to his battle against evil, the materialism of Canadian life seemed obscene.

While soldiers who return from battle often connect with one another and find support in their shared experience, the same isn’t true for a general. Dallaire couldn’t sit around with fellow veterans and talk about his fears over a beer. “I came home alone,” he writes.

Suicide became a reality. He thought about driving his car into a concrete bridge support. He cut himself extensively, swallowed pills. One of the problems with PTSD is that as the years go by, people expect the experience to fade. But it doesn’t fade; it comes back in nightmares and flashbacks and unwanted images. As Dallaire noted, it has always just happened, even 20 years after the fact. He developed a fear of himself and how he would react, triggered by a smell, a sound, a child’s face.

Dallaire showed remarkable courage in Rwanda and shows it again now with his descriptions of PTSD. It is, he writes, “a moral injury that ravages our minds, our souls.”

He emerged from the experience in Rwanda a different man, though he kept the best of the man who came before.

Advertisement