Drivers chat beside a Red Cross truck before taking their loads in search of marching prisoners of war. [International Red Cross]

The forced marches of Allied prisoners of war early in 1945 was both puzzling and harrowing. Puzzling because the German motives were unclear. Were they simply trying to evacuate PoWs from an active front as the Russians advanced? Were they hoping to use the PoWs as hostages and bargaining chips with the Western Allies, as at least one SS general suggested?

The marches were cruel ordeals, conducted during one of the coldest winters on record. Weather, starvation, disease, inadequate clothing and even Allied air attacks claimed about 2,200 British and Commonwealth prisoners (out of 180,000) while an estimated 1,120 American PoWs (of 94,000) also died. Amid such suffering, the courageous story of International Red Cross (IRC) relief convoys provides glimmers of hope and inspiration.

The first PoW evacuations began in July 1944 with movements of prisoners from Lithuania to Pomerania. The mass movement of prisoners began in late January 1945.

The average Allied PoW lost one-third of his body weight during captivity. Even before the marches began, bombing had shattered the German rail system, which carried foodstuffs for PoWs as well as munitions for their captors. One consignment of Red Cross parcels, intended for rail shipment in September 1944, did not leave Switzerland until November and only reached its destination in the latter half of February.

With the men now being force-marched across Germany, their situation worsened. The IRC strove to help. Many hands on both the Allied and the German sides became involved in an unusual project.

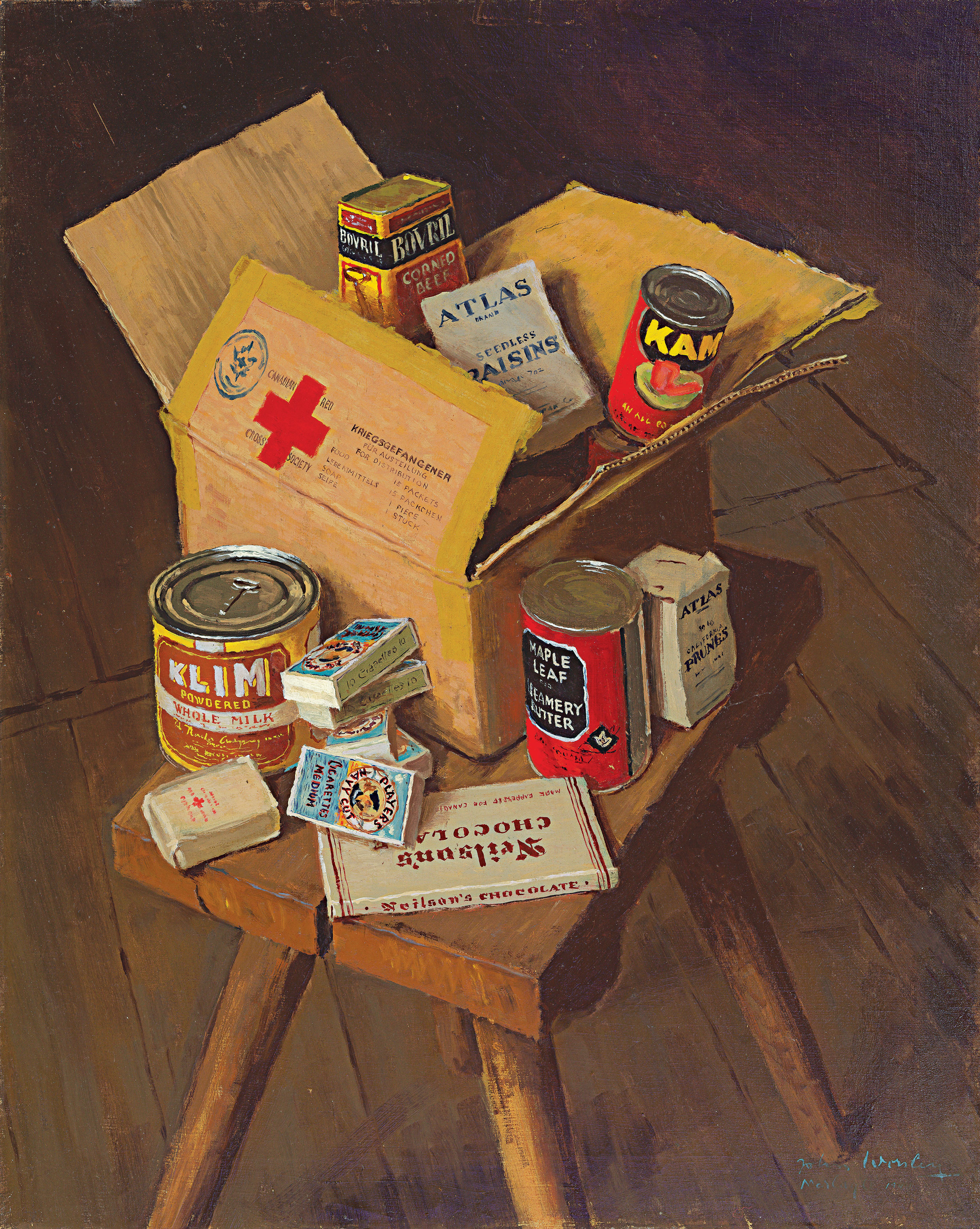

An open Red Cross parcel contains Klim powdered milk, corned beef, raisins, cigarettes, a chocolate bar and other rations. [IWM/LD5155]

The Allies had anticipated the problem. Late in 1944, nearly 300 vehicles were made available to the IRC via France and Switzerland, to relay supplies into Germany. Fifty were provided by the Canadian Red Cross.

German authorities co-operated as much as possible, but they could not halt the air raids or guarantee the safety of road convoys. The PoW columns were mixed in with flows of refugees, and German officers were themselves confused by changing orders as to routes and destinations. Trucks painted white with Red Cross markings would still be virtually invisible to medium bombers flying at 8,000 feet, but even Allied fighters occasionally strafed the roads indiscriminately. Conditions on the march were abysmal. A typical experience was that of Private Albert Pruden of the Lanark and Renfrew Scottish Regiment, who wrote in 1954: “Almost the entire march, we were forced to scrounge food, living off the land, except for a few occasions we were given a little bread and some baloney sausage. We were required to sleep in the open most of the time, without extra blankets. We travelled continuously every day until we were liberated.”

Private Alban James of the Royal Regiment of Canada, who had been captured at Dieppe, recalled his march from Stalag II-E in Poland at the end of his long captivity: “Marched about 30 kilometres per day. Not much food (after Red Cross food finished) until we received more Red Cross food about halfway through march. Sleeping in farm barns at night.”

A German guard watches as prisoners unload rations from the International Red Cross at Stalag Luft III in November 1941. [International Red Cross]

The situation reached a crisis point in March 1945. The International Red Cross redoubled its efforts, using railway stock borrowed from liberated France and Belgium. On March 6, a 50-car train left Switzerland, heading for southern Germany. It took two days to reach Stalag VII-A at Moosburg, northeast of Munich, one of the largest centres for Canadian Army PoWs.

Unprepared for its arrival, the camp commandant had no idea where to store the estimated 93,300 food parcels. The prisoners themselves rapidly unloaded the train. Most of the parcels were transferred to Red Cross trucks, and 3,000 were retained as a depot. This depot (which was restocked by trains on March 28 and April 12) was then placed under a double guard. Sixteen Allied soldiers watched the provisions while a German detail watched them. Access to the depot was with two keys: one kept by the camp commandant, the other by the prisoners’ man of confidence—a prisoner chosen to liaise with camp authorities, usually a senior non-commissioned officer.

The final distribution to isolated or marching captives, however, would be done by Allied trucks in Red Cross paint. The program could not depend on the German railway network, which grew ever more chaotic.

In its report on this operation, the IRC took considerable, and justifiable, pride in its work. But it overstated its case in one respect. In its published accounts, only Swiss nationals were mentioned as drivers. They failed to mention that a substantial number of drivers and mechanics were Allied prisoners of war.

Prisoners from Oflag IX-A/Z walk away from the village of Dachrieden in central Germany on their way east to Wimmelburg where they were liberated in early April 1945. [IMW/7098]

Chief among these was Regimental Sergeant Major Harry H. Stinson of the Lanark and Renfrew Scottish Regiment. He was the principal organizer among the PoW drivers. He screened applicants, sent men under guard to the Swiss border to accept vehicles, arranged to have them serviced in the German compound at Moosburg, and generally marshalled the relief convoys that subsequently fanned out across Germany.

As the relief train pulled into Moosburg, an IRC official (presumably accompanied by Stinson) asked for 12 volunteers to drive trucks in search of PoWs on the move or in marooned columns. There was no shortage of applicants, among them Company Sergeant Major Walter F. Moss of the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada, who became Stinson’s virtual second-in-command.

On March 8, they met a Swiss IRC official who explained the project in greater detail. At a time when German rail travel was barely possible, they were taken to Lübeck, on the Baltic coast, where a further 30 Canadians and 22 American prisoners were recruited, together with eight men of confidence who had arrived to draw rations for distant camps.

The group then re-crossed Germany by train to Constance on the Swiss-German border, where they took delivery of 50 General Motors and Chevrolet trucks. They could easily have escaped to Switzerland, but had given their word not to do so.

Ultimately, some 85 to 90 prisoners participated in the task, drawn almost equally from American and Canadian compounds, but including two British captives, one of whom was expert in first aid and the other serving as an interpreter. At least two drivers were volunteers from the columns being aided.

About two weeks after the trucks began rolling, Red Cross officials asked Stinson to divert about 15 vehicles to the Berlin area. He assigned Moss to head up this convoy, which plunged into the deadliest and most confused of all the closing battles. Both men survived the war, but they did not meet again during the course of the relief operations.

Red Cross parcels are issued from storage to former PoWs after the liberation of Stalag VII-A in Moosburg, Germany, in April 1945. [IMW/7098]

These operations were as peculiar as they were dangerous. The vehicles proceeded in groups of 10 to 15 at a time, with a few Swiss personnel as well as Canadians. A scout (usually an IRC official, sometimes a German soldier) explored ahead by car or motorcycle, finding the PoW columns.

Once one had been found, each marcher was given a parcel containing emergency provisions to last about five days. Limited supplies of soap and boot repair kits were also delivered. The hope was that the column would be overtaken by another convoy within five days. Between 14,000 and 18,000 PoWs were contacted during these drives.

Each truck was accompanied by a German guard. The Swiss and PoW drivers carried a permit issued by a senior SS officer, and countersigned by an IRC delegate, which declared the trucks and their loads to be “Property of the International Red Cross at Geneva.” To add bite, the document stated that anyone attempting to requisition the vehicles would be in breach of both international and military law and would be tried by a German military court. These certificates saved the day on several, though not all, occasions. SS troops hijacked one truck and stole part of the load from another.

There were other hazards. In searching for marching columns, the trucks came within range of German and Allied artillery fire, especially close to Berlin where the front was extremely fluid. Drivers and guards frequently dove for shelter as Allied aircraft attacked the convoys. In one such raid, four trucks were destroyed, two severely damaged, an American driver killed and two Canadians wounded.

A convoy of Red Cross trucks carrying supplies for prisoners forms up in Germany in January 1945. [International Red Cross]

Flight Lieutenant Robert Buckham had been shot down and captured in April 1943. His diary and drawings of Stalag Luft III were published in his book Forced March to Freedom in 1990.

“A Red Cross truck depot was located alongside the road on the edge of town,” he wrote while near Lübeck on April 23, 1945. “We approached, introduced ourselves, and were welcomed warmly by the truck drivers, who identified themselves as army NCOs, both American and Canadian, PoWs like ourselves.”

RCAF Group Captain Larry Wray witnessed much of this work. A prisoner himself from March 1944 on, he had become the Senior British Officer at Stalag Luft III in time to provide leadership during the forced marches of 1945. He was impressed by the courage of the drivers in what amounted to battlefield conditions, writing, “I have seen these drivers bring in trucks that were so shot up that it appeared only a miracle that the driver was alive.”

Artist Robert Marshall Buckham sketched a prisoner watching as Red Cross supplies are unloaded at Stalag Luft III prisoner of war camp. [Robert Marshall Buckham/CWM/19910176-036]

Moss showed extraordinary courage when, with the help of an IRC official, he spirited nearly 800 concentration camp inmates (“human wrecks” in one report) away from under the nose of the SS. He became a Member of the Order of the British Empire. The citation read in part:

“By extraordinary diplomacy and daring, he had these unfortunates loaded into trucks, 16 of which he took to Lübeck where they were loaded on Swedish ships and taken out of the country. The risk they took in the face of still-active Gestapo and SS is obvious.”

British troops liberated Lübeck on May 2, 1945, but the relief road convoys continued for another six days. Then the former Canadian and American PoWs turned their surviving vehicles over to Swiss Red Cross drivers and departed.

The courage and contributions of these drivers might not have received recognition but for Wray, who submitted a report on their actions. He described or confirmed several of the incidents already mentioned. Phrases such as “outstanding work” and “amazing record” ran through his text. Wray started the process of compiling the drivers’ names.

“If the record of these men can be found, I would deem it an honour to be permitted to recommend them for an award of gallantry,” his report said. “The task carried out by these men voluntarily was so gallant, so worthwhile, and so inspiring that Canada should be proud to recognize it by decoration.”

Liberated PoWs prepare to boarda Lancaster bomber at Lübeck aerodome to be flown to Britain in May 1945. [IMW/7098]

Operation Exodus

On April 17, 1945, as victory approached, the Allies began planning Operation Exodus—the evacuation of liberated prisoners of war from the continent.

The chief instrument was RAF Bomber Command, now running out of targets in a shrinking Germany. The PoW camps were widely dispersed and not necessarily close to airfields. Nevertheless, a general order was issued to all RAF bomber groups on April 20, 1945, and actual evacuations began on April 26 with 42 Lancaster bombers of No. 5 Group.

The pace increased in early May as the camps were overrun, the inmates taken to selected airfields, and the men flown back to England, with 20 to 25 per aircraft. In all, some 30,000 PoWs were evacuated by the RAF, the vast majority packed into the heavy bombers.

Even a humanitarian effort like Exodus had rules. The bombers had skeleton crews. Before departure, every PoW received a high carbohydrate ration and an air-sickness bag. Passengers were issued life jackets for the cross-Channel flights but no parachutes. Manifests were checked at both ends, lest some potential war criminals try to escape in the guise of PoWs.

“Violent manoeuvres are to be avoided,” pilot orders stated, “and aircraft are not to fly at heights which will cause distress to PoWs by reason of cold or lack of oxygen.”

The first RCAF crews involved were members of No. 405 Squadron. Early in May, they had participated in Operation Manna, dropping food to Dutch civilians, but on May 8 they were switched to Exodus. The unit flew 41 trips, carrying 947 former prisoners back to England.

The largest RCAF formation, No. 6 (Bomber) Group, also started Exodus flights on May 8. The group had already been tasked for operations in the Pacific (see “Tiger Force,” January/February 2005) and half the squadrons were engaged in re-equipping or preparing to return to Canada. That still left six RCAF bomber squadrons to evacuate PoWS, and eventually they moved 4,329 men in 180 sorties. The crews missed the largest VE-Day celebrations in England, but declared, “It was worth it just to witness the pleasure of the released officers and men on their return home.”

Three Canadian officers stand at ease at Oflag VII-C in Laufen, Germany, in August 1940. [International Red Cross]

Hazards and hardships

When Warrant Officer Frederick D. McMullen of the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada was made a Member of the Order of the British Empire, the citation described the hazards and hardships faced by many of the Red Cross relief convoy drivers:

Company Sergeant Major McMullen of the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada volunteered to head one group working from Stalag VII-A at Moosburg, Germany. He had under his command for most trips, some fifteen trucks and thirty men which rendered assistance to thousands of prisoners of war who were marching away from the rapidly advancing Allied armies. Without this assistance, rendered hourly for weeks, thousands of prisoners of war and distressed personnel might have suffered severe privation and even death from starvation. These men drove supplies under Company Sergeant Major McMullen’s leadership through German and Allied gunfire, under constant attacks from aircraft and through a populace that at any time might have found reason to exterminate them. Company Sergeant Major McMullen drove, as did all his men, as much as 48 hours at a stretch and for weeks on end existed on short snatches of sleep taken in the trucks or during a re-loading period, eating only on the move. There were many instances where men of his courageous group stopped only when they collapsed from exhaustion. The strain of driving huge trucks at high speed constantly under risk of attack from the air, frequently having to dive from the truck into a ditch, was exceedingly great. The initiative and mechanical ingenuity demonstrated by this group in servicing and rebuilding trucks from others shot up to a point of wreckage, is only exceeded by the bravery shown by daring to drive under such perilous conditions. As a result of this excellent organization, Company Sergeant Major McMullen was able to render desperately needed assistance to thousands of suffering and anxious people for a considerable period under the most difficult and dangerous conditions.

Advertisement