A supply convoy makes the five-kilometre crossing of the Mackenzie River to the Canol camp. [RICHARD S. FINNIE/LAC/PA-175986;]

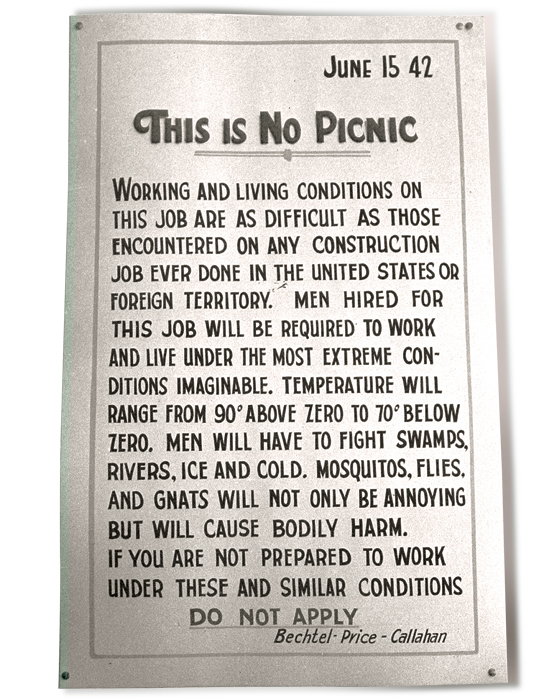

Early in 1943, an enticing notice offering jobs for men appeared in newspapers in Dallas, Denver, Minneapolis, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Seattle, New York, St. Louis and Tulsa.

It read: “Working and living conditions on this project are as difficult as those encountered on any construction job ever done in the United States or foreign territory. Men hired for this job will be required to work and live under the most extreme conditions imaginable. Temperature will range from 90 degrees above zero to 70 degrees below zero. Men will have to fight swamps, rivers, ice and cold. Mosquitoes, flies and gnats will not only be annoying but will cause bodily harm. If you are not prepared to work under these and similar conditions—DO NOT APPLY.”

But men did apply, attracted by good wages and the romance of Canada’s far north, known to Americans only by the writings of Jack London and others. The project itself was kept secret, known only as the Canol project. Even today there is some dispute over the name. While most sources say Canol was a contraction of Canadian Oil, some sources say it was a convoluted acronym for Canadian-American Norman Oil Line.

Whatever the truth about the name, the Canol pipeline went hand-in-hand with the building of the Alaska Highway, an engineering feat matched in the 20th century only by the building of the Panama Canal. Once the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, the U.S. was determined to secure a safe route for transporting personnel and supplies from mainland U.S. to Alaska. That meant building a road through Canada’s Yukon.

Once the highway was built though, oil was needed to be refined into gas, diesel and airplane fuel to support the military traffic to follow. Since the U.S. Navy could no longer guarantee safe passage of oil tankers on the Pacific Ocean, the question was, how does the fuel get there?

It was known that there was oil along the remote Mackenzie River in Canada’s Northwest Territories. Imperial Oil Ltd. had started a commercial operation in Norman Wells, N.W.T., in 1933. The oil had a wax base and would flow in extremely cold temperatures.

A top-secret plan was developed by the U.S. Army and the American Board of Economic Warfare to build a pipeline and its accompanying maintenance road from Norman Wells to Whitehorse, a distance of 825 kilometres. And why not? They had just finished the 2,451-kilometre Alaska Highway.

The army originally agreed to start the road from Whitehorse and work east, but it needed to create a private sector consortium to build the refinery and start the road west from Norman Wells. W.A. Bechtel Company and the W.E. Callahan Company were well-established construction companies while the H.C. Price Company was a well-known welding company. Together they formed the consortium of Bechtel-Price-Callahan (BPC). The Imperial Oil Company, under the direction of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, undertook to develop the field to its capacity. The project started in June and was supposed to be completed by Christmas.

All this was planned in the U.S. The War Committee of the Canadian Cabinet approved the project and granted permission to proceed. The House of Commons was informed just before the deal was signed.

The Whitehorse portion was simple enough. Supplies would come to Edmonton by rail and be shipped to Prince Rupert, B.C. There they would be reloaded onto barges and shipped along the coast to Skagway, Alaska, and then by rail again to Whitehorse.

The Norman Wells portion was more difficult. The Canol site was 2,400 kilometres north of Edmonton by the ordinary water route. There was no road, trail or railway. The end of the railway line was a Hudson’s Bay Company post at Waterways, 480 kilometres north of Edmonton. That left more than 1,600 kilometres of interconnecting rivers and lakes to reach the final destination.

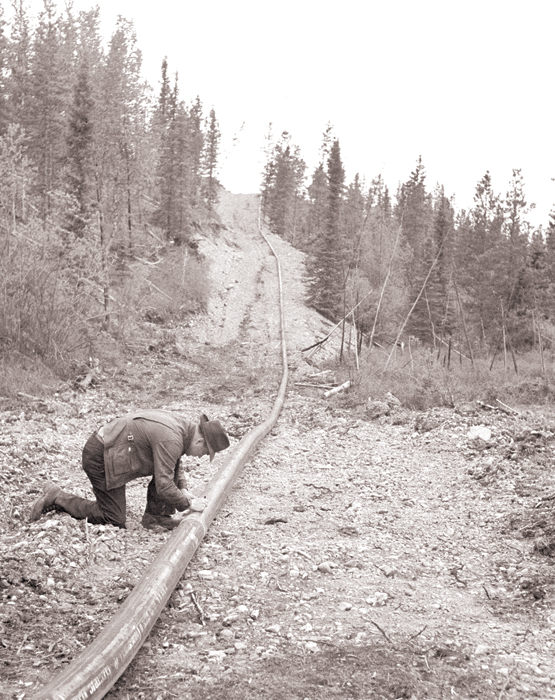

An oilman checks the welding on a section of the pipeline in June 1943. [HARRY ROWED/NFB/LAC/PA-174542]

With the short ice-free season from the beginning of July to the beginning of October, the workers would have a three-month window to ship supplies.

The herculean task is described in much detail in a document called Oil to Alaska by C.V. Myers. The undated document held by the McBride Museum in Whitehorse is marked “Passed by U.S. Censor” and

covers the period from the start-up to when the oil began to flow in 1944.

The first step was to build a camp at Waterways, now a suburb of Fort McMurray. It took 250 men to build the camp and unload the freight from the train onto barges. The barges had to take the Athabasca River to Lake Athabasca, cross the lake and enter the Slave River. But when they got to Fort Smith, the rapids were too dangerous to navigate.

The solution was to go overland. Huge trailers were built, big enough to accommodate the barges. Caterpillars were used to pull the barges onto trucks and move all the equipment overland 25 kilometres and into the water again. All this was done within 10 hours.

From there, the convoy followed the Slave River into Great Slave Lake, crossed it and moved into the Mackenzie River for the final portion of the trip.

Despite all this effort, only 18,000 tonnes of the 27,000 tonnes of supplies had been shipped before the winter freeze; some of it had sunk in the rough waters of Great Slave Lake.

Major-General W.W. Foster of the Canadian Army (below, at right) and his aide chat with workers on the pipeline in June 1943. [HARRY ROWED/NFB/LAC/PA-174543;]

A second phase of the supply link started in Peace River, Alta., where a new camp was built for the construction of a winter road, which was used successfully to transport 8,000 tonnes of equipment to Norman Wells.

When it was clear the job would not be finished by Christmas, schedules had to change and the Canol site had to be prepared for winter. The only communications possible would be by air. Airstrips were built at Embarras, Fort McMurray, Hay River, Providence, Simpson and Wrigley. How much the Canadian government knew about these side projects is still debated by historians.

Once the supplies got to the Canol site, the actual work could begin. The maintenance road had to be started and that meant crossing the formidable Mackenzie Mountains. BPC hired surveyor Guy Blanchet along with three native guides to blaze a trail by dogsled from the east. They followed a native route which took them through MacMillan Pass, which crosses the divide between the Mackenzie and Yukon rivers.

Three days before Christmas, 23 men under J.B. Porter, general superintendant for the construction company, set off in a convoy pulled by trackers. They were to set up an office and radio cabin, repair shop, two mess halls, bunkhouses, kitchen and kitchen storeroom. With temperatures at -60 ºC, they stopped sometimes every 15 minutes to thaw lines and repair vehicles. Motors were kept running all the time out of fear that they would freeze up.

Porter and his men cleared 170 kilometres in 47 days before fuel ran low and the crew returned to Norman Wells to wait for better weather. It would be another year of gruelling work, crossing mountains, streams and rivers, and dealing with permafrost and ferocious insects before the maintenance road was built. To the men on this job, once the road was built, laying the pipeline would seem easy.

On the west side of the project, army personnel who were to build the road from Whitehorse were called away to other duties. BPC took over responsibility for completing that section as well.

“The difference between the East Side and the West Side was that Whitehorse was accessible,” wrote Myers. “Canol was not. Whitehorse handled several projects simultaneously, built the refinery and employed thousands of men. Canol handled only one [project].”

The two crews were to meet up by Dec. 31, 1943. On Dec. 30, the two groups were 11 kilometres apart. The Whitehorse crew had brought up photographers for the historical meeting and had gone to bed, anticipating the historic event of meeting the Canol crew would follow easily the next day. But at three o’clock in the morning, the Canol bulldozers came crashing into the Whitehorse camp, having worked through the night to make the deadline. The photographers went back to Whitehorse disappointed.

Myers’ report comes to a rosy ending. It had been hoped that the Canol project would be able to produce 3,000 barrels of crude a day. Instead, it was able to produce up to 20,000 barrels a day.

According to Cryofront, the Electronic Journal of Cold Region Technology, between July and November 1944 the project provided all the motor vehicle requirements for military needs between Watson Lake and Fairbanks and also exported between 20 and 40 million litres to Skagway.

But it was hardly enough. The productivity did not match the cost. Twelve tankers full of oil were still making it through to Alaska while the Canol project was producing only the equivalent of one tanker load.

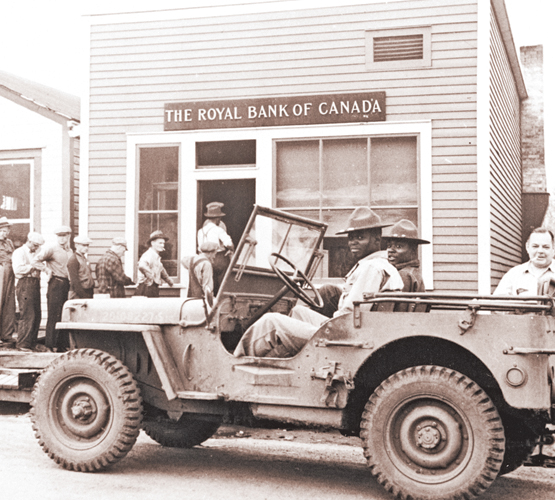

Bechtel employees and U.S. Army soldiers wait outside a bank in Fort McMurray, Alta., on payday during preparations to supply the Canol camp in August 1942. [ RICHARD S. FINNIE/LAC/PA-164900]

The Canol project was not the triumph of the Alaska Highway. The oil was pumped only from Dec. 19, 1943, to April 1, 1945. The refinery was sold in 1948 and moved to Leduc, where Alberta’s oil boom was beginning. The pipeline between Canol and Whitehorse was removed and used in other projects. Cabins, bridges, trucks and other equipment were simply abandoned and are still found there today by those adventurous enough to go there.

From an estimated cost of $30 million, the final cost of the project had been $134 million, prompting a scathing review by a U.S. Senate inquiry headed by Harry Truman, shortly before he became president of the United States. In the end, U.S. Undersecretary of War Robert P. Peterson conceded, “I suppose that we must bow to the verdict, that the project was useless and a waste of public funds.”

Whatever the waste of U.S. public funds, the Canol project did have its benefit to Canada. The airstrips were the beginning of a system that would open much of Canada’s north in the years following the Second World War.

Today, the Northwest Territories portion of the road has become the Canol Heritage Trail, running 355 kilometres from Norman Wells through the Mackenzie Mountains to the Yukon border. Most hikers take 14 to 22 days to complete the trail.

Only the Yukon portion of the road is still usable, but travellers with rugged vehicles must be prepared to bring the extra fuel and food needed, as there are no stores or gas stations along the way. Once they reach the end, there is no alternative but to turn around and drive back the way they came.

Advertisement