The Royal Air Force marked its 100th anniversary with a parade and flypast over Buckingham Palace on July 10. More than 100 aircraft from all eras flew over central London. [RAF]

Indeed, Britain’s “finest hour,” as Prime Minister Winston Churchill called it, came mainly thanks to RAF pilots, whose staunch defence and willing sacrifice against overwhelming odds dealt Hitler his first defeat, stopped his western advance in its tracks and bought Allied nations the time they needed to win the Second World War in Europe.

“Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few,” said the pugnacious, cigar-chomping, war-time prime minister whose taste for Pol Roger champagne, vintage Hine brandy and Johnny Walker Red was itself the stuff of legend.

Now an integral part of the British school curriculum, the Battle of Britain was recent history to a young Drew Anderson and a foundation of the history on which he was raised.

Growing up in the little village of Tillicoultry in central Scotland, he built models of iconic RAF planes such as the Hurricane, Spitfire and Lancaster. He attended his first airshow at RAF Leuchars near St. Andrews at three years old and watched films like The Battle of Britain and The Dambusters with his dad.

He dreamed of the day he would become an RAF pilot in the tradition of Battle of Britain heroes like Douglas Bader, Peter Townshend and Sailor Malan—names that roll off his lips at least as readily as those of Nelson, Wellington or Montgomery.

The Battle of Britain, he says, is “part of who we are as Brits and as a nation and we celebrate that fact…and what the RAF offers to the nation and beyond.”

At 18, Anderson did join the RAF but his destiny was as an aero-systems engineer, not a pilot. He was commissioned in 1991 and is now, some 36 years after signing up, a squadron leader serving as a liaison officer in Ottawa.

RAF Squadron Leader Drew Anderson with the Vintage Wings of Canada Spitfire Mk IX. [Stephen J. Thorne / Legion Magazine]

It’s an ideal location for the stories he has to tell—home to airworthy historical standards like Spitfire, Corsair, P-40 and Mustang fighters along with other icons such as the Swordfish, Lysander and Harvard. In one corner, a Hurricane is currently in rebuild mode, its ribs in full view.

Original working examples of the legendary Rolls Royce Merlin engine are virtually everywhere on the floor.

A Hurricane fighter in rebuild at Vintage Wings of Canada in Gatineau, Que. [Stephen J. Thorne / Legion Magazine]

The Battle of Britain was the young RAF’s coming of age, and it ranks with the greatest defences in a British history that is replete with epic tales of conquest and defeat on its shores. Roman centurions invaded in 55 BC, followed by the Anglo-Saxons, the Viking raiders and, finally, the Normans.

1,000 RAF personnel in front of Buckingham Palace in celebration of the 100th anniversary. [Victoria Jones / PA]

It was the last great threat to English sovereignty before Hitler’s forces chased British and Allied troops from French soil at Dunkirk in 1940, leaving the British Isles—and the RAF—as the last line of defence against Nazi tyranny.

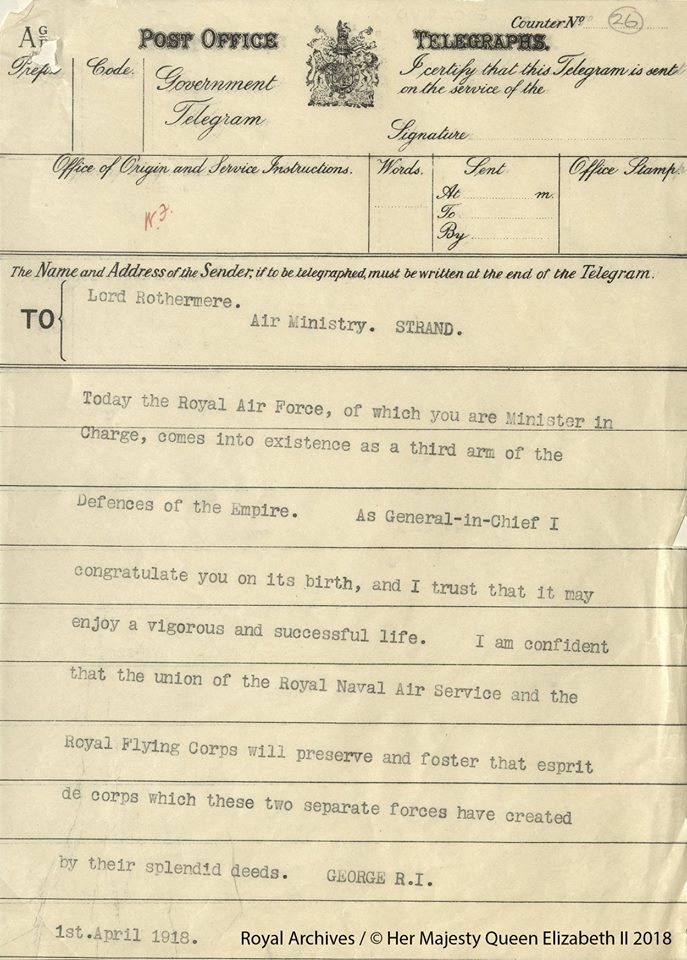

For the RAF, formed in April 1918 out of the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service, it was do or die.

“I don’t think a lot of people really understand how close it was,” said Anderson. “We were successful because we were fighting over our own country, we could pick our battles.”

Radar enabled planners to choose where they put their squadrons and when they deployed them to optimize limited fuel capacity and a finite contingent of pilots, who could—and often did—conduct multiple intercepts a day and were often back in the air within 24 hours of being shot down.

The German attackers, on the other hand, had fuel enough for mere minutes over their targets. Though more experienced than their Allied foes, those who were shot down were in most cases permanently lost to the Nazi war effort, whether they survived or not.

British aircraft production, however, was losing ground to the Germans’ vast resources and unrelenting attacks. It was not until Churchill ordered a raid on Berlin and Hitler responded by directing the Luftwaffe to shift its focus from RAF airfields to London that the RAF was able to adequately reconstitute and mount a decisive defence.

They finally turned the tide of battle on Sept. 15, 1940, and ended it six weeks later. Hitler’s attention would turn eastward, to the Soviet Union, and the D-Day buildup in Britain would eventually begin.

A telegram sent on 1 April 1918, from King George V to Lord Rothermere, President of the Air Council, on the creation of the Royal Air Force saying, “As General-in-Chief I congratulate you on its birth, and I trust that it may enjoy a vigorous and successful life. [Royal Archives]

Canadians flew in RAF squadrons, protected RAF bombers, played key roles in the RAF’s dam-busting raid into the heart of industrial Germany and flew hand-in-hand with their RAF comrades the entire Second World War.

Wing Commander James E. (Johnnie) Johnson, Britain’s top ace with 38 kills, led Canadians through much of his war-time service. As commander of No. 127 Wing RCAF, part of the RAF Second Tactical Air Force under No. 83 Group RAF, Johnson and his Canadians were the first Allied flyers to land on French soil after D-Day.

With the call-sign Greycap Leader, he was a respected, even beloved commander. After D-Day, he had the supplementary fuel tanks removed from beneath his Spitfires’ wings and replaced with barrels of beer for his Normandy-based pilots.

Under the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, RAF recruits came to Canada to earn their wings alongside Canadians, Australians and New Zealanders—in all, 131,553 aircrew, including pilots, wireless operators, air gunners, and navigators, at 151 schools across the country.

Anderson said his young audiences have been engaged, each bringing new challenges and queries to the events where he and others talk not just about the RAF and RCAF but, with living references at hand, they explain the workings of aircraft and their advances, as well as pay tribute to those who fought and died.

Pilot Peter Ashwood-Smith gives aircraft engineering students a rundown of his Pitts Special stunt plane during an education day at Vintage Wings of Canada in Gatineau, Que. [Stephen J. Thorne / Legion Magazine]

“For me on a military exchange assignment here in Canada, it is important to relay the RAF 100 message because Canada and Canadians have played a very significant role in the success of the RAF, especially in its formative and through the world war years.”

Advertisement