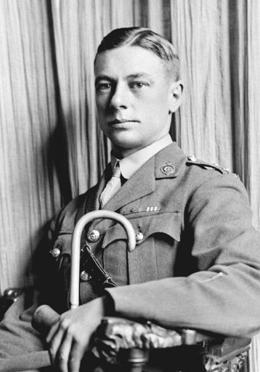

Lieutenant George Mullin in 1918. [Wikimedia]

He would soon be proven right on one of those counts.

Mere hours later, amid the Battle of Passchendaele, Mullin’s “gallantry and fearlessness,” as his Victoria Cross citation reads, earned him a place among a select few awarded the British Empire’s highest military accolade.

Rarer still was his unique position within the esteemed and courageous group: an American-born recipient.

Instituted in 1856, the Victoria Cross has since been pinned upon the chests of at least five individuals from the United States, four of whom received it for service with Canadian forces during the First World War.

Fifty-three years before Mullin’s exploits, however, William Henry Harrison Seeley of Topsham, Maine, had technically been the first-ever American recipient.

On Sept. 6, 1864, Seeley had been an ordinary seaman in the British Royal Navy—and a long way from home. While Union and Confederate armies clashed on American battlefields, the young sailor found himself part of efforts to reopen Japan’s Shimonoseki Straits to European and U.S. trade.

There, having joined a shore party tasked with silencing enemy gun batteries, Seeley performed several courageous acts worthy of recognition. Notably, after reconnoitring Japanese positions, the ordinary seaman was said to have recovered a wounded commanding officer while under intense fire.

Seeley’s devotion to duty, though seldom mentioned in British or American history, marked the beginning of the United States’ curious connection to the Victoria Cross. On Oct. 30, 1917, Mullin—who died 61 years ago this week—opened a new chapter.

Bullets ripped through Mullin’s clothes—somehow without hitting him—as he rushed the next pillbox.

Mullin was not like the tens of thousands of U.S. citizens who crossed the border prior to America’s own entry into the war. The Portland, Ore., native had learned to shoot a rifle while hunting prairie chickens near Moosomin, Sask., after his family moved there when he was two years old.

After the 1914 call to arms, Mullin eventually joined Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI). Deployed to France, he quickly acquired a reputation as a skilled sniper—and for taking great personal risks.

His first real brush with death came on June 2, 1916, when he was wounded at the Battle of Mount Sorrel near Ypres. After recovering, Mullin returned to combat duties within the La Folie Sector at Vimy Ridge, where he later earned the Military Medal for daring actions against an enemy position.

It was nevertheless during the bloody Battle of Passchendaele that the American-born, Canadian-raised soldier made a name for himself.

Assaulting the Meetcheele ridge overlooking Passchendaele village, the men of PPCLI had already, in the words of one witness, been “mowed down like wheat” when the Canadians came across a particularly menacing German pillbox.

Lieutenant Hugh McKenzie, a PPCLI officer attached to the 7th Canadian Machine Gun Company, rallied nearby survivors and launched a frontal attack against the stronghold. Intent on distracting the enemy gunners while others flanked the pillbox, the 31-year-old subaltern was killed in the charge.

McKenzie’s efforts, which had the desired effect of diverting German fire, would be posthumously recognized with the Victoria Cross. Meanwhile, Mullin was in the process of earning his own.

The American carefully inched his way toward the concrete emplacement. When the right moment came, he leapt up and tossed grenades into an enemy sniper’s post; the bombs instantly knocked it out.

Bullets ripped through Mullin’s clothes—somehow without hitting him—as he rushed the next pillbox. Alone, revolver in hand, he clambered onto the roof before angling the weapon inside and firing. The German gunners fell.

Finally, having saved his pinned-down comrades, Mullin edged around to the post’s entrance and compelled the remaining defenders to surrender.

Including the late McKenzie, four Canadian soldiers were awarded the Victoria Cross at least in part for their actions on Oct. 30, 1917. However, of those, Mullin had the distinct honour of being the only American-born recipient.

Five Americans have been presented the Victoria Cross—along with a debated sixth—a final medal is held by the United States’ Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

On Aug. 9, 1918, Sergeant Raphael Louis Zengel of Faribault, Minn., became the second American VC serving with Canada. During the Battle of Amiens, Zengel single-handedly stormed a German machine-gun post and inspired his men forward. “By his boldness and prompt action,” reads Zengel’s citation, “he undoubtedly saved the lives of many of his comrades.”

Captain Bellenden Seymour Hutcheson of Mount Carmel, Ill., followed suit on Sept. 2, 1918. Under withering artillery and small-arms fire near Arras, the medical officer ensured that all wounded comrades received care. At one stage, he rushed forward in full view of the enemy to treat a wounded Canadian sergeant. Hutcheson’s Victoria Cross citation notes his “utter disregard of personal safety…until every wounded man had been attended to.”

That same day, Lance-Corporal William Henry Metcalf of Waite Township, Maine, likewise earned the Victoria Cross during the Second Battle of Arras. Recognizing that his unit had been held up, and having noticed a friendly tank nearby, Metcalf stood in front of the armoured vehicle with a signal flag and directed it along the German trench.

“The machine-gun strong points were overcome, very heavy casualties were inflicted on the enemy, and a very critical situation was relieved,” reads the statement accompanying his award.

Among the five confirmed holders is a potential sixth whose U.S. credentials have been questioned. Most records state that Corporal Frederick George Coppins, who performed actions similar to Raphael Louis Zengel’s—also on Aug. 9, 1918—was born in Charing, England. Yet other sources allude to his place of birth being California, where he is known to have later retired and died.

While five Americans have been presented the Victoria Cross—along with a debated sixth—a final American medal is held by the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Arlington National Cemetery, Va. This was a reciprocity act after the U.S. Congress approved awarding the Medal of Honor to the British Unknown Warrior. Both tombs now hold both decorations.

It’s perhaps noteworthy that no U.S.-born recipient emerged from the Second World War, nor the years since, although their absence is no reflection on their contributions to Canada.

Instead, individuals such as George Mullin stand testament to the enduring bonds between the two countries.

Advertisement