“Generals January and February mount guard for the Canadian people all year round,” historian Charles P. Snow opined in 1940, to general agreement and relief. The Second World War was to change that opinion.

Adolph Hitler sent more than three million troops to invade Russia on June 22, 1941, mistakenly believing Russia would capitulate to his blitzkrieg as quickly as western European nations at the beginning of the war.

German troops at the Soviet state border marker, 22 June 1941.[Wikipedia]

Not only were the troops still in summer uniforms, but “Weapons malfunctioned. Vehicles wouldn’t start. Frostbite cases soared. Troops froze to death,” wrote Dwight Jon Zimmerman in a DefenceMediaNetwork article titled “Hitler’s Winter Blunder.”

German soldier tending to his comrade.[Wikipedia]

Realizing its north was vulnerable to winter attack, the Canadian military decided it should become a global expert in winter warfare and began training troops and developing and adapting equipment, clothing and operational methods for missions conducted in temperatures as low as -40 C.

In early 1945, a winter exercise was held in Saskatchewan to test soldiers and equipment in intense cold and low humidity. The training would also determine winter’s effect on mobility and combat efficiency.

The 1,750 personnel included infantry from the King’s Own Rifles of Canada, signals specialists, engineers, transport experts and gunners. They were to advance nearly 300 kilometres north from Prince Albert over ground covered with 45 centimetres of snow, along rutted roads and through muskeg.

The troops were to respond to a scenario recreating field conditions of a faux attack by Japanese forces. It involved a surprise amphibious and airborne assault through Alaska and into Canada, during which key airfields were seized.

Squadron Leader Charles H. “Smokey” Stover, who had earned a Distinguished Flying Cross in May 1944, commanded the Royal Canadian Air Force Army Co-operation unit, which primarily flew ski-equipped Noorduyn Norseman.

The Brigade Group, commanded by Colonel D.C. Stephenson, moved out at dawn on Jan. 16, 1945. They soon discovered making progress by foot would be slow: the maximum distance that could be achieved while wearing snowshoes was only about 25 kilometres a day.

Among lessons learned: tracked vehicles were needed as trucks got bogged down travelling over muskeg not yet solidly frozen; “bombs” dropped on frozen lakes did not disrupt travel across the ice, but merely left small holes when they broke through the surface; telephone wires could be laid from the air.

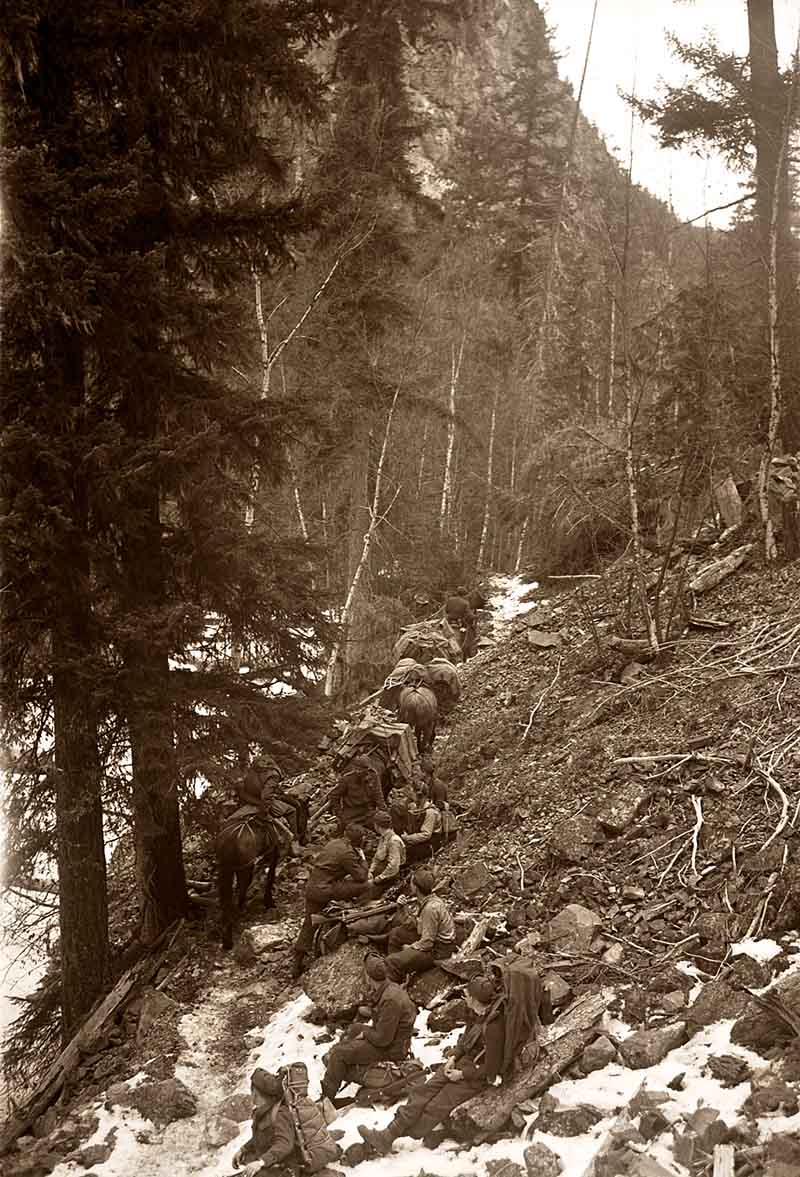

Another exercise, called “Polar Bear” tested the performance of 1,150 soldiers and materiel under wet and cold conditions in mountainous northern British Columbia in March 1945. Most of the troops were from the 1st Battalion and Prince Albert Volunteers, but some personnel included medical, signals, armoured, artillery, engineering, transport and army service corps units, plus Dakota and Norseman aircraft.

The scenario for this training also involved a spearhead Japanese force, this time landed by submarine, to build a road for a subsequent larger force. The Canadians moved by snowshoe, horse and snowmobile. The men tested out hauling artillery by travois pulled by horses. In this exercise they encountered conditions varying from wet coastal terrain to three metres of snow in the mountains.

Soldiers trekking uphill with pack horses through mountainous terrain in the polar bear exercise[Northern BC Archives & Special Collections]

One unusual task for pilots was dropping hay bales and oats to feed the horses. (A couple of times hay bales struck the tails of the Dakota transports).

One observation from the tests was that men could survive in harsh terrain in winter conditions, but if they had to pack or drag their own supplies, they wouldn’t have enough energy to work or fight.

The journey was fraught with difficulties, including stuck vehicles, loss of radio communications and navigational problems.

The next exercise, “Lemming,” showed that there are differences between winter and Arctic warfare.

A convoy of six vehicles, two snow tractors, army sledges and traditional Inuit sleds were to carry a small party testing snow vehicles on sea ice and barren ground on a 1,000-kilometre round trip from Churchill, Man., to Padlei, N.W.T. (present-day Nunavut). The main objective was to gather information on how to extend operations in sub-Arctic conditions, explore areas for future winter exercises and test snow vehicles.

A small party left Churchill on March 22, 1945, and returned April 6. The journey was fraught with difficulties, including stuck vehicles, loss of radio communications and navigational problems.

With no roads or railheads for movement in the Arctic, units would have to be self-sufficient or supplied by air. But missions were possible, reported the commander.

“The exercise proved that the inaccessibility of the Arctic is just another myth,” wrote Lieutenant-Colonel Patrick Baird. “Providing supplies are assured, operations on the barren grounds which represent one third of Canada’s area can be as unhindered as operations on the Libyan deserts.”

He recommended development of snow vehicles, and that training continue.

Today, tracked snow vehicles are regularly used during the annual Arctic exercises of Canadian Armed Forces.

Advertisement