Paratroopers of the 1st Airborne Division (left), including Canadian Lieutenant Leo Heaps (below, standing far right), descend over the Netherlands in September 1944. Several Canadian officers similarly served under the Canloan program with other British units such as the 15th (Scottish) Infantry Division, shown here near Nijmegen, Netherlands, in February 1945. [Michael M. Dean/DND/LAC/PA-145675]

Heaps

Lieutenant Leo Heaps, drifting gently from the heavens in his parachute over the Netherlands, felt he shouldn’t be there.

Above him an early afternoon sun shone brightly that Sept. 17, 1944. Below, the fields of Wolfheze—a Dutch village—were bursting with sunflowers, their sight catching the 21-year-old Canadian officer’s eye.

All seemed relatively quiet. No enemy gunfire; just the droning sound of innumerable C-47 transport aircraft dropping their cargo of airborne troops sent into action for Operation Market Garden.

Except Heaps of Winnipeg was neither on a Canadian mission nor even under Canadian command. This was the British 1st Battalion, Parachute Regiment, a part of the 1st Airborne Division.

And it was his first jump, ever.

Things started to unravel—literally—when Heaps’ kit bag broke loose, showering his belongings across the countryside. He then realized his trajectory was sending him toward a cluster of pine trees, their uninviting branches edging ever closer.

But it was too late.

Paratroopers of the 1st Airborne Division (left), including Canadian Lieutenant Leo Heaps (below, standing far right), descend over the Netherlands in September 1944. Several Canadian officers similarly served under the Canloan program with other British units such as the 15th (Scottish) Infantry Division, shown here near Nijmegen, Netherlands, in February 1945. [Wikimedia]

In a sense, however, Heaps was not alone.

He, like 672 other Canadian officers seconded to the British Army under the Canloan scheme, was indeed exactly where he needed to be—even if his immediate circumstances were less than ideal.

By the fall of 1943, following a succession of costly campaigns, British forces had been plunged into an acute labour crisis. Authorities needed to fill the ranks of lieutenants and captains. No stone was left unturned.

The expansion of the Canadian Army, meanwhile, had created a surplus of junior officers, a situation caused by an almost too efficient promotion system and the disbandment of home defence formations.

It seemed only a matter of time before one of those stones was used to kill two birds, realized in full in September 1943, when Ottawa requested that the Canadian Military Headquarters in London determine whether the British Army could absorb any of these officers.

Ultimately, both countries came to an agreement.

Paratroopers of the 1st Airborne Division (left), including Canadian Lieutenant Leo Heaps (below, standing far right), descend over the Netherlands in September 1944. Several Canadian officers similarly served under the Canloan program with other British units such as the 15th (Scottish) Infantry Division, shown here near Nijmegen, Netherlands, in February 1945. [Airborne Forces Museum]

The primary condition laid out by the British was that the bulk of the transferred officers would be subalterns (below the rank of captain), although a proportion could be captains at a rough ratio of 1:8 in favour of lieutenants.

For the Canadians, there were several conditions: that the Canloan scheme be entirely voluntary; that officers should be loaned with the understanding that they could be recalled if required; that Canada should be responsible for pay; that age limits should meet Canadian Army criteria; that their service be restricted to the European and Mediterranean theatres (excluding a few exceptions to the rule further down the line); and that Canada would select volunteers that the British Army would accept without question.

It was likewise agreed that any junior officer deemed worthy of promotion could rise through the British ranks, and any deemed unsuitable for service could be returned to the Canadian Army after a trial period.

Given estimates suggesting up to 2,000 potential candidates, not only infantry, but also a small number of ordinance officers, there were high expectations for the initiative and calls went out across the country. Many answered.

Fendick

Lieutenant Reginald (Rex) Fendick of The Saint John Fusiliers (Machine Gun) walked through the mess doors in Prince George, B.C., to a commotion.

All he had wanted was a hot drink and a bedtime snack after enduring hours on the bus from leave in Vancouver. Now, he was being asked if he wanted to join the British Army, a strange turn of events that Sunday in March 1944.

Tired of home defence duties and the National Resources Mobilization Act conscripts (nicknamed “zombies” for their unwillingness to serve overseas), it seemed like the perfect opportunity for someone like him.

The reasons for participating in the program, of course, differed between officers—be they natural-born Canadians, Americans who had crossed the border, or even Britons who had emigrated prior to the war. However, as a rule of thumb, boredom and disillusionment with service in Canada were leading factors in the decision-making process, often coupled with the fundamental desire to be part of the invasion of Western Europe.

Thus, the New Brunswicker was gone by the end of the month—along with five of his willing comrades—en route to Camp Sussex in his home province.

There, a facility designated A-34 Special Officers’ Training Centre had been established as an intensive, three-week refresher course commanded by Brigadier Milton Gregg, a WW I Victoria Cross recipient.

That didn’t alleviate the inevitable culture shock. Fendick and his colleagues occasionally misunderstood each other’s accents and turns of phrase.

The centre’s syllabus stressed physical fitness, weapons training, night operations, field works—including mines and booby traps—infantry tactics, leadership and personnel management. Additionally, officers were expected to have a basic grasp of British regimental traditions and even mess etiquette.

Fendick was far from the only individual to find the instruction tedious, even if Gregg was highly respected.

It was during Fendick’s time at Sussex that he met Leo Heaps, feet planted on a desk as he tore folded paper to create a string of paper dolls. “If they’re going to treat us like children,” Heaps reasoned, “we

may as well behave like children.”

Still, the refresher course at A-34 served its purpose, providing Canloan officers with an opportunity to hone their skills and bond before departing for Britain in nine groups or “flights.”

Fendick joined the largest group of 250 officers on May 3, comprising the entire second intake, and arrived in Liverpool on May 11. From there he travelled to the Grand Central Hotel in the Marylebone area of London.

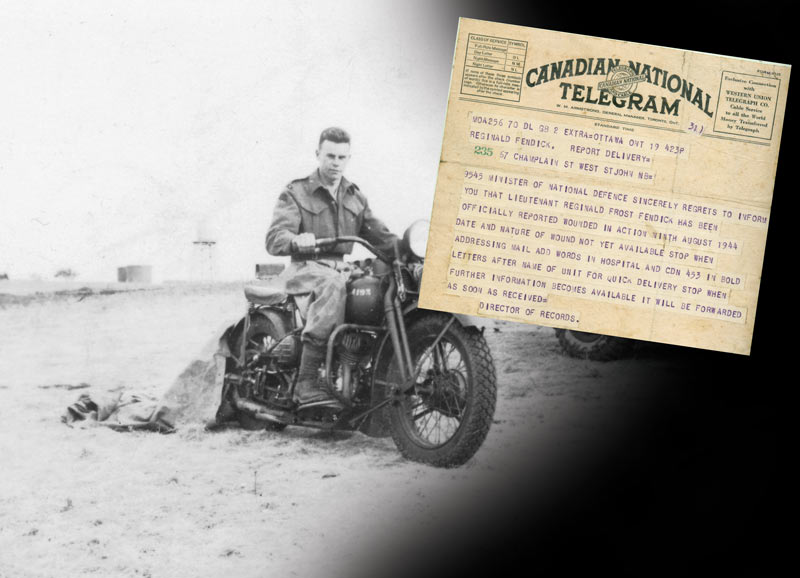

Lieutenant Reginald (Rex) Fendick served with the King’s Own Scottish Fusiliers under the Canloan program. He was wounded in August 1944, but recovered and fought again in the Korean War.[Vickers MG Collection/Research Association, courtesy of Reg Fendick]

“We were assembled in a large lobby…with many small tables set up around all sides of the room, each manned by one or two British staff officers and clerks,” the young Canadian lieutenant later wrote.

“Each table had a sign over it, naming one or more British regiments. We were invited to go to the table of our choice, where we were told which regiments and battalions had vacancies, and we were invited to choose our unit.”

Pleased to find space in the King’s Own Scottish Borderers, which was affiliated with his former Saint John Fusiliers, Fendick soon found himself bound for southeast England in preparation for Operation Overlord.

He, like all Canloan officers, was then provided with a distinct identification number—his being CDN 453—that became unique to the scheme, and a “Canada” flash emblazoned on his British battledress.

Where possible, successive groups of subalterns were similarly afforded the chance to join affiliated British regiments, the most successful being The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada, its members joining the United Kingdom’s Black Watch. Elsewhere, soldiers from The Seaforth Highlanders of Canada served in the British Seaforth Highlanders, as did some of those once belonging to the Pictou Highlanders.

But that didn’t alleviate the inevitable culture shock. Though glad to be commanding his own platoon of lowland Scots, Fendick and his colleagues occasionally misunderstood each other’s accents and turns of phrase. At one stage, it took a Midlander English sergeant to translate.

The use of the word “colonial” by superiors also became a source of frustration among a few Canadian lieutenants and captains.

Yet despite the odd hurdle, Canloan officers adapted to their circumstances, ironed out any personal difficulties and became integral to their respective formations, earning the rightful respect of their comrades.

In Fendick’s case, his familiarization period proved short. Anticipating the need to replace casualties after D-Day, he was sent to a Reinforcement Holding Unit and instructed to wait.

His moment would come, but for now, staring out to sea from Folkestone, Fendick saw the vast armada crossing the English Channel. It was early June 1944, and the Canloan scheme was about to face its first true test.

Robertson

Canadian Lieutenant Leonard Robertson (above, second from left) hit Sword Beach on D-Day with the 2nd Battalion, East Yorkshire Regiment. [Code Word Canloan]

Lieutenant Leonard Robertson—designated CDN 192—was in the armada.

Originally attached to The Dufferin and Haldimand Rifles of Canada, he had been posted to the 2nd Battalion, East Yorkshire Regiment.

On June 6, he hit Sword Beach, one of two Canloan platoon commanders in ‘C’ Company (the other, CND 118 Captain James (Mac) McGregor).

The landing craft ramp dropped and Robertson, along with a couple of his men, charged ahead, only to realize when it was already too late, that they had not yet reached the shore. The trio had unwittingly launched themselves into the water, its depth luckily shallow enough to recover and wade ahead.

Meanwhile, “Bullets, shrapnel and what have you was flying around like a swarm of angry bees,” the lieutenant noted.

One of his privates was struck and fell. Robertson grabbed the wounded soldier and dragged him the rest of the way, mindful of the bodies floating face down in the wake, their blood flowing freely from fatal wounds.

Unfortunately, the private was struck again.

Urgently needing to get off the beach, Robertson organized his platoon and pushed forward through the maelstrom.

It mattered not that his life, upbringing and experiences more than 4,800 kilometres away differed from those of the British troops beneath him. The moment called for leadership, and that’s what the Canadian officer could provide.

Venturing inland by June 7 brought little respite, with Robertson’s 15 Platoon and Mac’s 14 Platoon confronting a German pillbox.

“Mac had gone up to the entrance and called on them to surrender,” said Robertson. “They didn’t give him a chance, but cut him down with a burst of gun fire hitting him in the chest and stomach…Mac was dead.”

McGregor was the first Canloan officer recorded as killed in action. He would not be the last.

Between D-Day and the end of August 1944 in Normandy, 77 Canloan officers were killed or died of their wounds on patrols, in slit trenches and throughout various operations. More would come. But they had likewise established themselves to be capable and valued leaders with the clear capacity to inspire courage and fortitude in the British Second Army soldiers they commanded.

MacLellan

Canadian Lieutenant C. Roger MacLellan (left) with fellow Canloan officers Kip MacLean and Ken Coates at a training facility in June 1943. [Wave An Arm, “Follow me!”]

Lieutenant C. Roger MacLellan—designated CDN 554—of New Glasgow, N.S., and a Canloan officer in the British 2nd Battalion, Glasgow Highlanders, was about to prove those very same capabilities in the battle for Ghent in the Netherlands.

It was Sept. 10, 1944, and his platoon had been tasked with clearing houses around the Canal du Nord.

As was the case by then with so many Canloan officers after the relentless combat of several months, MacLellan—previously of the Pictou Highlanders—had cultivated a strong bond with his men.

He needed only to wave his left arm and bellow, “Follow me,” leading from the front as always, and his sections would fall into place.

Yet it was not long until a German machine gun opened up on them in the street. Enemy rifle fire joined the cacophony, and the platoon was pinned down. But MacLellan maintained his nerve.

With his left section in position to provide covering fire, he ordered an aggressive response. Their intense pressure appeared to be tipping the scales until MacLellan’s left section spied an 88mm gun.

Repeated attempts to neutralize the position seemingly failed—even with the surprise arrival of tank support. And all the while, casualties were mounting.

MacLellan ordered the evacuation of the wounded as he and two men covered a withdrawal. The lieutenant was the last to leave, carrying his Sten and a Bren through a blanket of smoke.

Unbeknownst to the officer at the time, the platoon and armour combined had succeeded in silencing the German artillery. Noteworthy, too, had been MacLellan’s “great coolness and ability…[and] utter disregard for his own personal safety,” noted his Military Cross citation.

Canloan officers across multiple British regiments earned many such accolades, including 41 Military Crosses (MC), among several other honours from the French, Belgians and Americans.

Few British soldiers, no matter the rank, doubted qualities of their Canadian numbers by that stage. In one instance, D-Day veteran Robertson—himself a Military Cross recipient—asked his men to choose between a British and Canloan officer for a replacement. Their decision was unanimous: “Bring us the goddamned Canadian.”

Moved to Geel, Belgium, after his MC-earning actions, MacLellan participated in a church parade before listening to a padre’s sermon. Midway through the service, however, he and his men felt reverberations coming from outside. Everyone filtered through the doors and stared up into the sky, awed by the sight of countless aircraft almost shrouding the horizon.

It was Sept. 17, 1944.

They had established themselves to be capable and valued leaders with the clear capacity to inspire the British Second Army soldiers they commanded.

The mossy ground cushioned Heaps’ parachuted descent.

Miraculously, he was unscathed. The Winnipegger—designated CDN 415—dusted himself off.

His duties, unlike most subalterns, were to take on special assignments at his liberty, the result of there being no other rank-appropriate positions available. The first came the next day, having been instructed to take a jeep laden with supplies and a wireless operator to Arnhem bridge.

Joined by a Dutch guide, they promptly got into trouble when the vehicle’s steering wheel came off in Heaps’ hands, hurling the three of them into an embankment—though for the most part they were unharmed.

The determined lieutenant then flagged down a Bren carrier, hitched a ride and continued into the devastated city of Arnhem.

Major-General Roy Urquhart watched with bemusement as the mismatched party arrived at his beleaguered headquarters, an encounter made stranger still when Heaps, believed by the commander to have a “charmed existence,” reported news from elsewhere along the front.

The Canadian’s role thereafter shifted from supplier to messenger. Over the coming days, Heaps acted as a vital communications link between the divisional headquarters at Hartenstein Hotel and, wherever humanly possible, the often isolated and increasingly desperate pockets of airborne troops. He even—on his own initiative—crossed the River Rhine in a dinghy more than once, intent on contacting the forward elements of XXX Corps, which was expected to bring much-needed relief to the overwhelmed force.

His luck ran out, however, while guiding the 4th Battalion, Dorset Regiment over the Rhine. The unit was set to launch a midnight attack to bolster the battered airborne, but Heaps was pinned down by enemy fire after making the crossing.

Despite slipping into the water to escape, he was captured.

Heaps spent a brief period in a prisoner-of-war holding camp, undoubtedly acutely aware of his Jewishness, and befriended a couple of British prisoners.

En route via train to Germany, armed with a tiny silk map, a box of matches, a button compass, a pair of nail clippers, a blanket and a tin of chocolate, the three cut a barely man-sized opening in a carriage porthole and jumped.

But Heaps’ story would not end there.

The Canloan officer made it back across Allied lines, whereupon he received authorization to team up with the Dutch resistance and help retrieve fellow evaders in the wake of Operation Market Garden.

Not only did he receive the Military Cross for his exploits, but he left behind a legacy synonymous with the success of the Canloan program.

That small yet significant legacy, fostered by Heaps and his fellow Canloan officers, remains a great source of pride in military circles on both sides of the Atlantic—albeit largely unknown on a grander scale.

Fendick shared Heaps’ so-called charmed existence when his carrier struck a mine in August 1944. He sustained serious wounds, but was evacuated to hospital, recovered and was sent back to action. He later fought in the Korean War and eventually rose through the ranks to lieutenant-colonel.

Robertson also suffered from a series of minor wounds that required treatment. Within a couple of weeks, however, he also returned to his unit and continued to serve with distinction. One of his postwar achievements included serving as vice president for the Canloan Army Officers Association.

MacLellan returned to his education after the conflict. Qualifying as a research scientist in entomology, his work contributed considerably to agricultural pest management procedures. MacLellan likewise rejoined the service, commanding the West Nova Scotia Regiment from 1960-1962.

Finally, Heaps ran unsuccessfully for political office, but found another avenue for service when he organized efforts to assist refugees amid the 1956 Hungarian revolt—a feat he repeated with locals during the Vietnam War. In addition to becoming an esteemed art dealer, he authored several books, notably Escape from Arnhem and The Grey Goose of Arnhem.

These individuals, in many respects, were fortunate. There was a 75 per cent casualty rate in the nearly 700-strong—623 infantry officers and 50 from the Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps—Canadian group seconded to British regiments in the summer of 1944. Of those, 128 never returned home.

Their sacrifices have been recognized through the Canloan National Memorial in Ottawa, a similar monument at 5th Canadian Division Support Base in Gagetown, N.B., and a plaque at the residence of the British High Commissioner to Canada.

Perhaps above all else, they are remembered by the ever-dwindling number of British veterans who, recalling the outstanding leadership of their Canloan comrades, still hold Canada’s wartime contribution in high regard.

The Canadian Army encountered many of its countrymen serving in British units during its campaign to liberate the Netherlands, including as it moved toward the Rhine River near Xanten, Germany, in March 1945. [Barney J. Gloster/DND/LAC/PA-137734]

Advertisement