The blast tunnel that serves as the entrance to the Diefenbunker is designed to funnel shockwaves in one end and out the other. This image shows half the tunnel, from the spot where recessed doors allow access to the facility.[Stephen J. Thorne]

It’s revealing commentary on Canada’s constitutional commitment to “peace, order and good government” that, in the event of nuclear holocaust, the country’s Cold War-era politicians and bureaucrats were expected to keep calm and carry on far below ground.

Deep in the recesses of the former Canadian Forces Station Carp near Ottawa, better known as the Diefenbunker, nameplates still identify the provisional offices of such seemingly peripheral ministries as Fisheries and Oceans, Employment and Immigration and, more pointedly perhaps, Health and Welfare.

Mirrors gave patrolling guards a preview of what was around corners in passageways surrounding the Bank of Canada vault. Government offices never had to be used[Stephen J. Thorne]

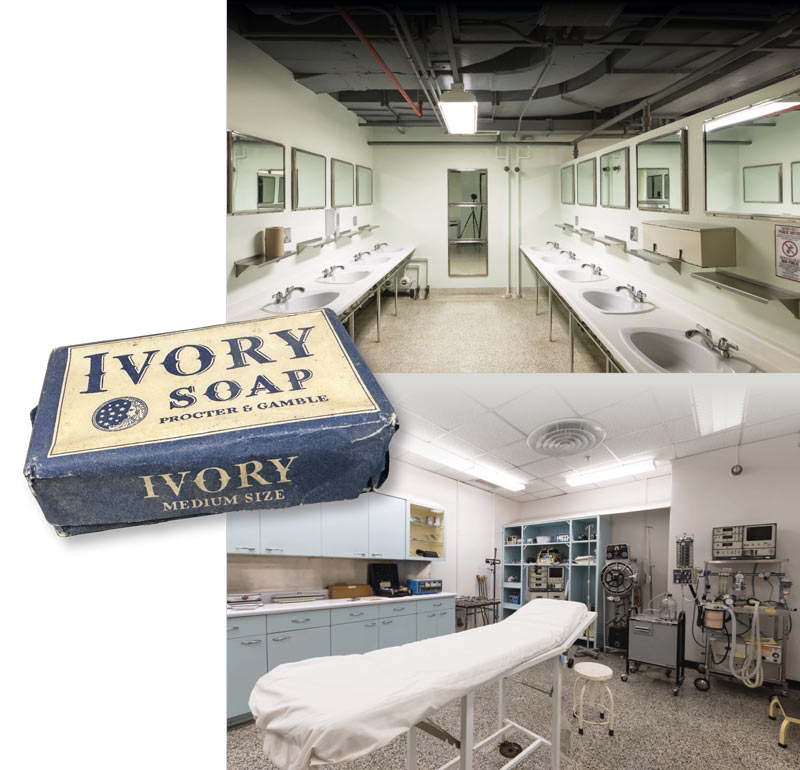

Decontamination showers and Geiger counters were at the ready.[Stephen J. Thorne]

A CANEX tuck shop sold cigarettes, snacks and necessities, such as aftershave and Brylcreem.[Stephen J. Thorne]

Cupboards and pantries serving the modernist-style cafeteria were stocked with enough fresh food and rations to sustain 535 people for 30 days.[Stephen J. Thorne]

Some four storeys down, beyond the decontamination showers and Geiger counters, around the corner and down the hall from a modernist-style cafeteria and a CANEX still stocked with Brylcreem and Aqua Velva, there lies a massive vault in which 725 tonnes of the country’s gold could be stored behind a 12-tonne door.

It was here, in this 300-room, 9,300-square-metre, reinforced concrete bunker and fallout shelter where 535 civil and military authorities, sans loved ones, were to take up residence beneath a gravel pit and run the country had the Red Menace launched nuclear missiles on North America.

Ironically, Prime Minister John Diefenbaker—who sanctioned the bunker’s construction in 1959—never set foot in the place, and is said to have vowed he never would, declaring he couldn’t leave behind his beloved wife Olive.

His resolve was never put to the test. The closest it came was during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, when Diefenbaker’s administration created plans to move government operations underground.

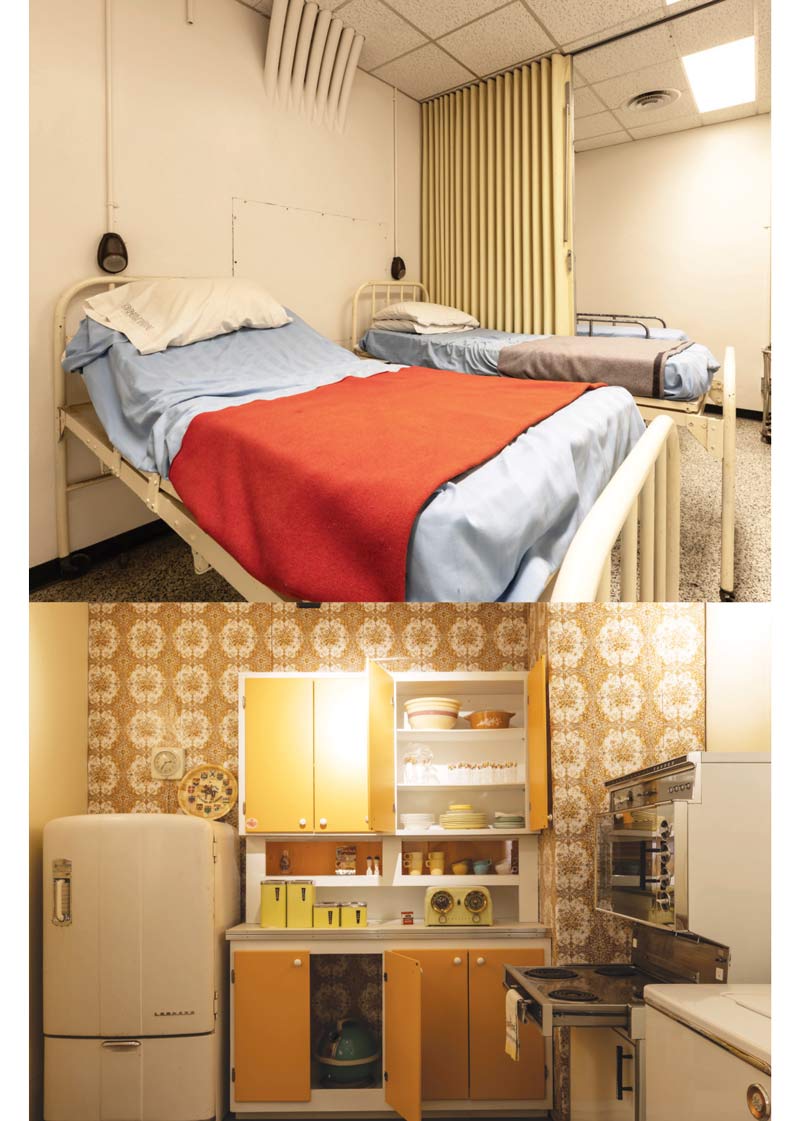

The prime minister’s quarters included a small bed, a spartan bathroom and offices for the leader and his secretary.[Stephen J. Thorne]

Prime Minister John Diefenbaker—who sanctioned the bunker’s construction in 1959—NEVER set foot in the place.

A 1970s-era computer disc drive the size of a coffee table stored just five megabytes, a fraction of a modern cellphone’s capacity.[Stephen J. Thorne]

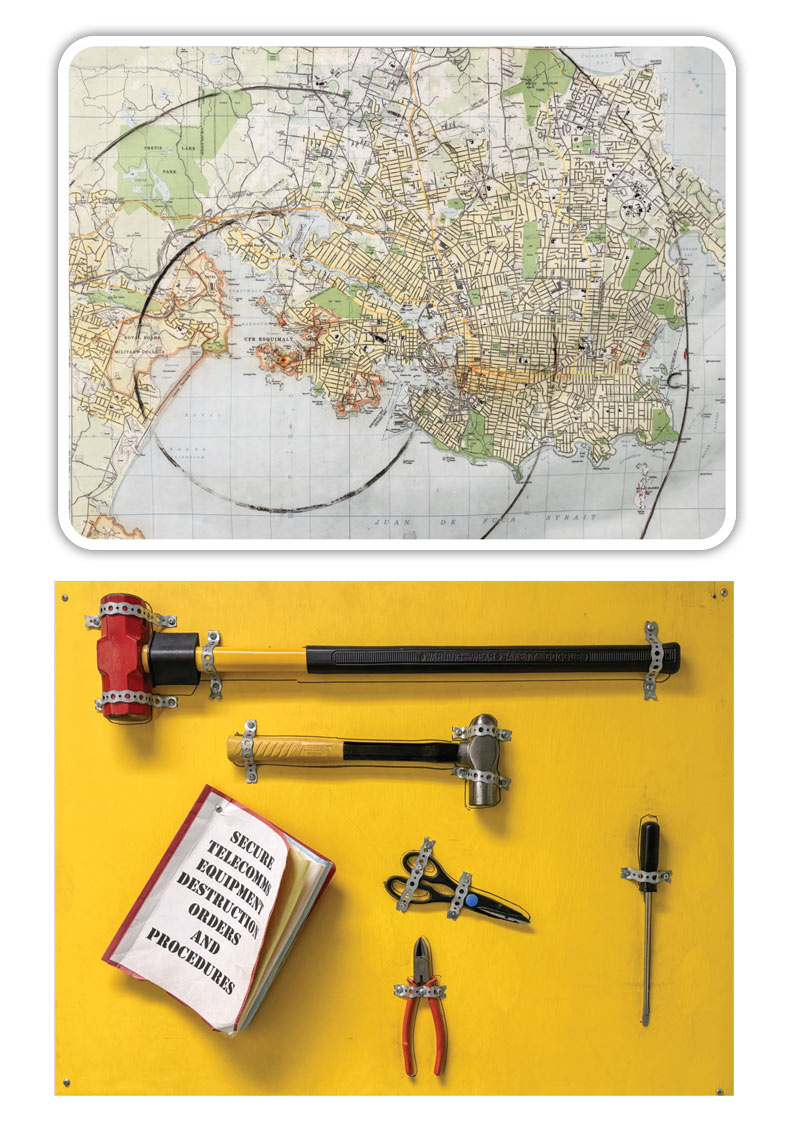

A map shows the destruction zones of a nuclear strike on Esquimalt, B.C. Tools were on hand to destroy sensitive equipment should the site be overrun.[Stephen J. Thorne]

At a time when Canadian schoolchildren were conditioned to periodic air-raid drills, bunker personnel were reminded daily of the threat’s immediacy and implications.

The 115-metre-long blast tunnel that served as the facility entrance was designed to withstand an explosion equivalent to five million tonnes of TNT from as close as 1.8 kilometres away. Midway along the passage, recessed 1.8-tonne doors take you into the actual facility and its decontamination showers.

A map on the wall of a room two storeys underground shows the estimated blast zone of a nuclear warhead dropped on the naval base at Esquimalt, B.C. A sledgehammer and other tools were on hand to destroy sensitive equipment should the site be overrun during an invasion.

The war cabinet room.[Stephen J. Thorne]

“Do not leave yourself open to exploitation: alcohol abuse, gambling, black market, bribery, drug abuse, sexual promiscuity.”

Living in spartan, shared accommodations, rotating staff were subjected to constant scrutiny and warnings of more shadowy manifestations of the enemy from behind the Iron Curtain.

“Hostile intelligence agents are searching for personnel susceptible to subversion,” declares a poster splayed across a desk in the Civil Situation Centre. “Do not leave yourself open to exploitation: alcohol abuse, gambling, black market, bribery, drug abuse, sexual promiscuity.”

The infirmary was equipped with beds and 1950s-era medical equipment. A typical kitchen had all the amenities a 1960s homemaker could want.[Stephen J. Thorne]

The women’s washroom had sinks and mirrors aplenty. The surgery was stocked with enough equipment to address most trauma injuries.[Stephen J. Thorne]

One of nearly 50 so-called “Emergency Government Headquarters” built under Diefenbaker’s Continuity of Government plan, the bunker existed as a communications and civil defence hub until 1994. It’s now a Cold War museum and the sprawling bank vault is a theatre and conference/reception hall.

The Bank of Canada vault could hold 725 tonnes of gold behind its 12-tonne door.[Stephen J. Thorne]

Advertisement