Stories about war brides travelling to Canada from the United Kingdom and other European countries following the Second World War are commonplace. But little is known about those war brides who happened to be widows—women who had married a Canadian soldier, only to lose him before fighting ended. It’s believed fewer than five per cent of all war brides ended up in this circumstance. What was it like to be a war bride widow?

The widows likely shared much in common with their fellow war brides, yet in other respects, their lot was unique. Their lives were filled with loss and uncertainty rather than hopeful excitement for a future to be shared with new husbands and families in new homes overseas.

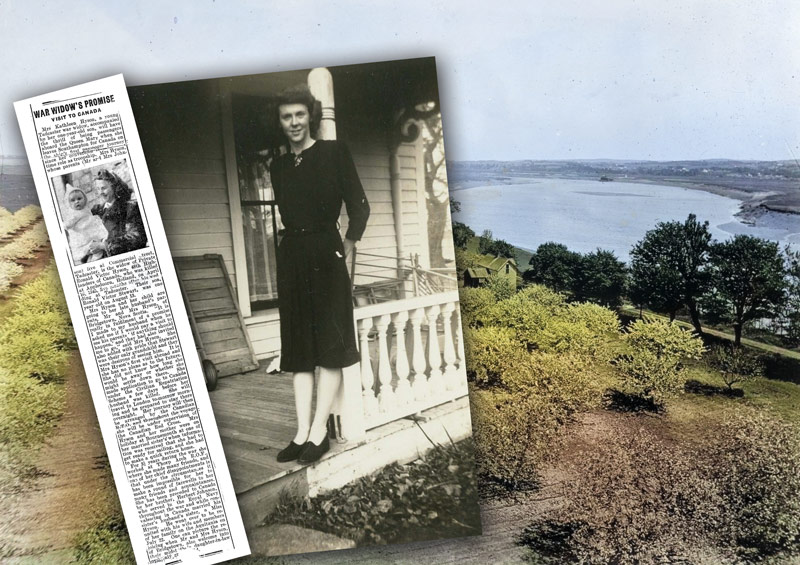

My mother Kathleen was a war bride widow, and she was interviewed by a reporter just before coming to Canada. The 1946 newspaper clipping makes for an informative source of details about her situation and the uncertainties that lay ahead—as enlightening as her own memories, filtered as they may be by the passage of time.

She fulfilled a promise to her husband that she would take their baby to see his parents in Bridgetown, N.S., after the war if something should happen to him.

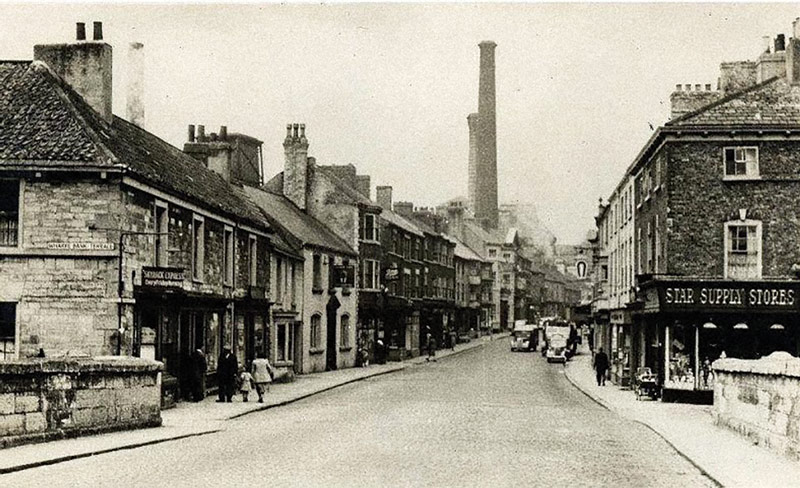

Kathleen was born in August 1922 and raised in a working-class family in the small British town of Tadcaster. In early 1943, the British government recruited women her age for war-related service, and she found work making bombs and shells at Royal Ordnance Factory 8 in Thorp Arch, not far from her parents’ home.

She met Canadian Private Ronald (Ron) Hyson around that time and they were wed on Nov. 3, 1944. Although Canadian Army Routine Order 788 had officially dissuaded soldiers from marrying while overseas, nearly 45,000 Canadian military personnel married British women and another 3,000 married women from other European nations during the war.

Following the marriage, Kathleen remained at her parents’ home in Tadcaster, where I was born in August 1945. Meanwhile, Ron returned to the battlefield with the 48th Highlanders of Canada. He was killed in action in the Netherlands on April 16, 1945, during the Battle of Apeldoorn—one day before the Canadians liberated the city.

After the end of the war, life was gradually returning to normal. Kathleen was on vacation with me and her mother visiting a sister in Bournemouth, England, in August 1946, when a letter arrived saying that she should pack immediately for a voyage to Canada. Ottawa’s policy was to provide the wives and children of Canadian soldiers with a free trip to Canada for family reunification. This arrangement extended to war brides who had become widows.

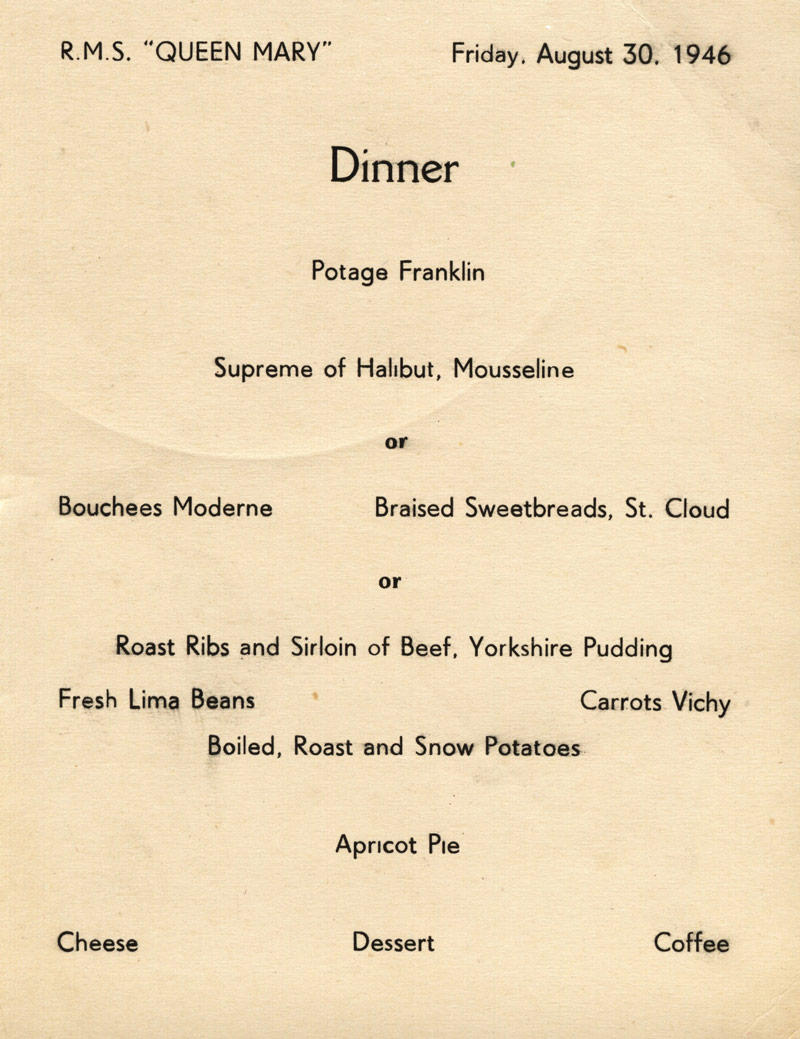

Kathleen returned to Tadcaster the same day to collect her belongings for the trip. She headed to London the next day for an overnight stay. War brides and their children who had been selected for the trip stayed at collection-point hotels in the city, then were transported the following morning via train to Southampton to catch the Queen Mary ocean liner.

Everything seemed to proceed at a breathtaking pace within a few days: notification, gathering in London and train departure for the ship. It was so quick that Kathleen bemoaned to the newspaper reporter that she had not had time to say goodbye to her mates at work.

This fast and efficient pace was possible because much of the preparatory paperwork had already been finalized. For starters, Kathleen had applied in early 1945 under the repatriation scheme for ship transport to Canada. It fulfilled a promise to her husband that she would take their baby to see his parents in Bridgetown, N.S., after the war if something should happen to him.

The Canadian Wives’ Bureau in London had also played a leading role in England by alerting every war bride to the regulations and facilitating the booking of hotels for the London stay and arranging for soldiers to assist the women in transporting luggage to the train and the ship. Thus, all had proceeded smoothly once the Queen Mary was ready to depart on Aug. 28, 1946.

Despite the preparations, many were overwhelmed by the sight of the ship—by both its size and its legacy. Soldiers again assisted carrying light baggage aboard, while deckhands stored heavier luggage not required during the voyage in the ship’s holds. Accommodation attendants greeted the passengers on arrival and directed them to their assigned rooms. Members of the Canadian Red Cross were available to assist during the trip.

Some women found the ship’s shared quarters crowded. But others, especially those with children, saw benefit in companionship: the mutual support to keep an eye on the little ones during the long voyage. And they welcomed any helping hands in an age before disposable diapers, as the rooms were soon littered with washed nappies hanging to dry wherever space was available.

Conversation, however, could be difficult for those who were widows. Most newlyweds were filled with excitement, enthused by the prospect of reconnecting with their husbands and starting life anew in Canada. It was hard, however, for my mother to partake in these joyous conversations. As she had earlier told the British reporter, except for a visit with her in-laws, she did not know how long her stay would be, and she had no future plans. Everything was uncertain.

There was one bright spot, however. Her older brother Herbert was to greet her on arrival in Nova Scotia. After he had seen action with the Royal Navy in the North Atlantic early in the war, he had taken a rest break in Nova Scotia. Herbert had stayed with Kempton and Grace Hyson (my father’s parents) and their family, prompting him to suggest later that my dad should take his breaks from the battle with his parents in Tadcaster. This led to Mom and Dad meeting. (And Herbert had married one of Ron’s sisters, Leila.)

Other than this meeting, everything else on my mother’s horizon was cloudy. How long would she stay? Would she return to England? How would she get along with her in-laws? What about her finances? Where would she live or find a job?

These questions haunted my mother during her voyage. Her worries were not helped by seasickness. After years of food rationing in England, most war brides were impressed by the variety and quantity of food available on the ship. But not my mother. Soon after departure, she was queasy. She could consume only saltine crackers to help settle her stomach. Cabin mates had to bring back the crackers for my mother because she found it difficult to walk on the moving ship to go to the cafeteria. My mother was not alone in this matter—Queen Mary had a poor reputation for its ability to handle heavy seas, even after the installation of stabilizers in 1958.

Her malaise was not helped when I contracted chicken pox. Being a widow and single mother, she had always had to look after me herself regardless of her own ailments. So, the ship’s limited medical staff provided my mother with calamine lotion to apply regularly to my skin to reduce the itching.

On arrival in Halifax at Pier 21, soldiers once again assisted in carrying luggage and small children off the ship. And Red Cross staff made certain that families caught the appropriate train to take them to their respective destinations across Canada. Fortunately, our train trip through southwestern Nova Scotia was relatively short, though it provided a memorable vista of the Annapolis Valley. Uncle Herbie greeted us in Bridgetown.

She was a young widow with no home of her own, no job and no prospects for the future.

My mother’s seasickness soon disappeared, only to be replaced with the pangs of homesickness. It was not uncommon for war brides to miss their former lives, but some, like my mother, had it far worse than others. This was understandable. British and Canadian villages were worlds apart in terms of daily lifestyle. My mother was used to the compact lifestyle of small English towns where friends, shops, pubs and other amenities were within an easy stroll, with ready access by public transit for longer outings.

Such features were absent at my grandparents’ home. They lived on a farm on the eastern edge of Bridgetown surrounded by apple orchards and pastureland. It was a considerable walk to the downtown shopping area, with no opportunity for my mother to develop friendships or find employment. This sense of isolation grew worse, the passing weeks contributing to her homesickness.

My mother’s earlier words to the British reporter still echoed true. She was a young widow with no home of her own, no job and no prospects for the future. Feelings of loss ruled her all day long. It was not surprising, therefore, that she decided to return to her British roots and the familiarity of Tadcaster in August 1947.

It was not long, however, before my mother realized that coming back to England had been a mistake. Homesickness is a poor guide in life—no way to advance. Despite her previous difficulties in Nova Scotia, back to Canada we went in October 1948. This time, my mother toughed-out her bouts of homesickness.

During her initial trip overseas, she had met her brother-in-law Merrill. They fell in love, and upon her return, they married on Feb. 5, 1949. My mother told me that I now had three fathers: God, my father killed in the war and my new dad. We settled in Hantsport, N.S., and I eventually welcomed three siblings to our family.

As we grew older, my mother shifted from a housewife role to operating a beauty salon in the mid-1960s. She later worked at the local Sears. She died in October 2015, 11 years after Merrill’s passing. She led an eventful life with its share of ups and downs. Yet, in its way, it was fulfilling, even if not the one she expected.

Advertisement