VIDEO INTERVIEW: Legion Magazine sat down with Tim Cook, author and historian at the Canadian War Museum, to discuss the Museum’s recent acquisition (on loan) of a Canadian 18-pound field gun that is said to have fired its last shots at Mons immediately before the armistice was signed in a railroad car outside Compiégne, France, terminating the slaughter at about nine million soldiers on all sides, including 68,000 Canadians.

Story originally published in March 2018.

King Philippe and Queen Mathilde of Belgium toured the Canadian War Museum. The King thanked Canadians for their sacrifices in two world wars. [Stephen J. Thorne]

Canadian 18-pound field guns, ubiquitous among Allied forces between 1914 and 1918, are said to have fired their last shots at Mons immediately before the armistice was signed in a railroad car outside Compiégne, France, terminating the slaughter at about nine million soldiers on all sides, including 68,000 Canadians.

Two of those guns were left behind as gifts from Canada to the City of Mons in 1919. One has come back on long-term loan to the Canadian War Museum where the occasion was marked on March 13 by a visit from Belgium’s King Philippe and Queen Mathilde.

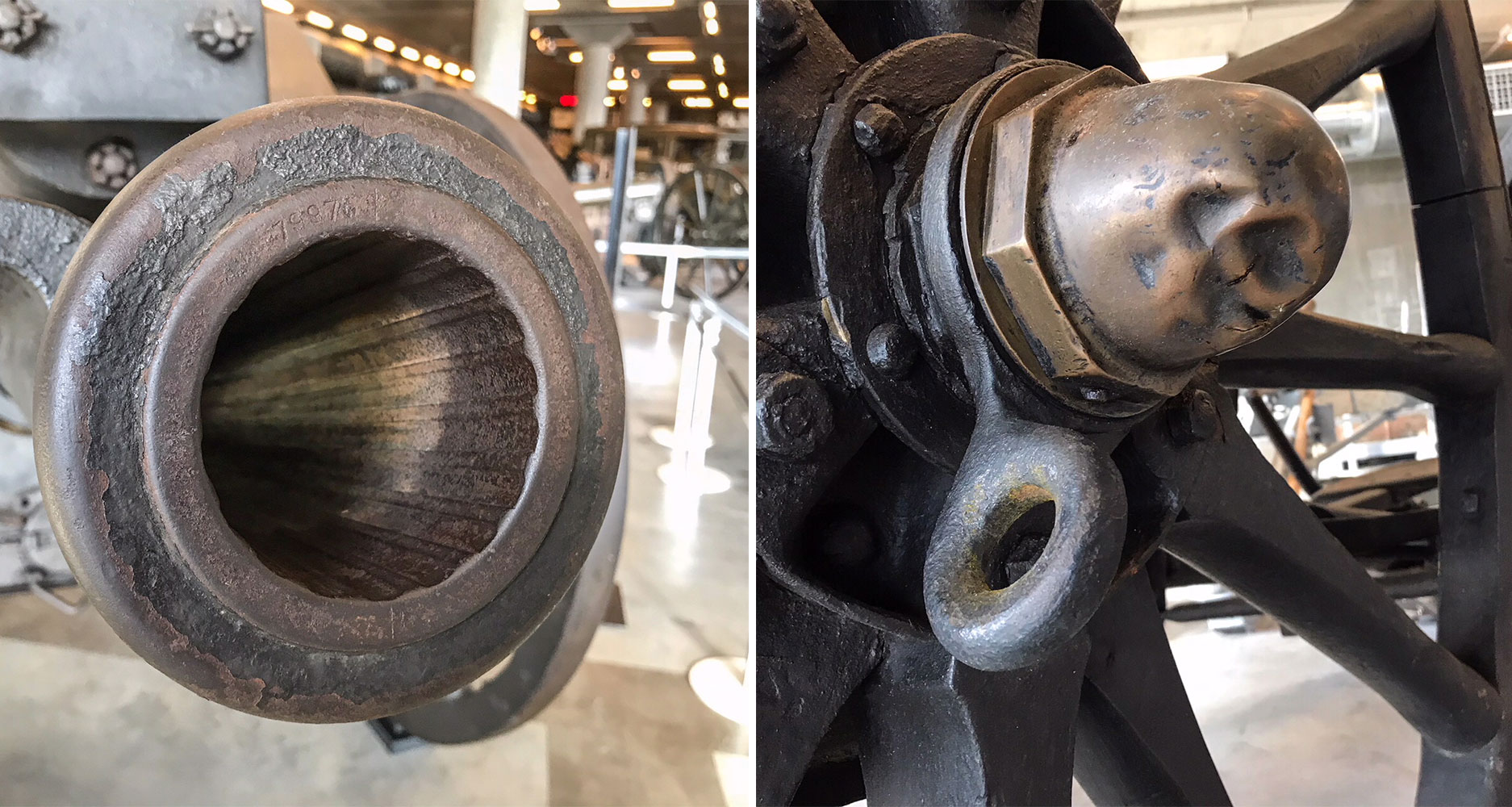

One of the 18-pound field guns Canadian artillery fired in the liberation of Mons during the last hours of the First World War. It was one of two given to the city after the war and has now been placed on long-term loan to the Canadian War Museum. [Stephen J. Thorne]

The Canadian Expeditionary Force began and ended the war in Belgium, from Ypres, where they faced one of the world’s first chemical attacks in 1915 and 6,000 died, to Flanders, where John McCrae wrote his immortal poem just a month later.

They fought at Passchendaele in 1917 where 2,600 Canadians were killed, and on to the Belgian villages they liberated on the road to Mons—names like Marchipont, Baisieux, Elouges and Quiévrain. There was La Croix, Hensies, Boussu-Bois, Petit Hornu, Epinois and Bois de l’Eveque. The list goes on: Saint-Aybert. The Condé Canal. Dour. All taken in the war’s final week.

Tyne Cot Cemetery near Ypres, Belgium is the final resting place of 35,000 soldiers of the British Commonwealth. Many were killed in the Third Battle of Ypres, also known as the Battle of Passchendaele. [Stephanie Slegtenhorst]

Among them is George Price of Falmouth, N.S., recognized as the last soldier of the British Empire to die in the First World War. He was shot in Ville-sur-Haine, south of Mons, two minutes before the armistice was signed. A member of the 28th Battalion, Saskatchewan North West Regiment—known as the Nor’westers—the 25-year-old private is one of two Canadians buried in the city’s Saint-Symphorien Military Cemetery.

It would be just a quarter-century before Canadian uniforms returned to Belgium to fight another war, taking a lead role in opening the Scheldt River estuary, gateway to the Belgian port of Antwerp. More than 1,800 died in the fall 1944 campaign.

The First World War field gun belonged to the 39th Battery, Canadian Field Artillery, which joined the fight in 1916 and fought at the Somme, Vimy Ridge and Passchendaele, culminating in Canada’s Hundred Days, a series of offensives during which the Canadian Corps spearheaded the armies of the British Empire.

The 39th Battery brought the gun into Mons and deployed it on the Champ de Mars, where it was fired in support of infantry and cavalry units. Canadian military brass presented it to the city in August 1919 and it was displayed in the Mons Memorial Museum. Museum curators hid it from German occupiers during the Second World War.

The gun is in exquisite condition, no doubt reconditioned since it was given to the Mons museum. But among the telltale signs of the hard ground it has travelled are its worn spoked wheels and a dented brass hub.

King Philippe and Queen Mathilde of Belgium speak with veterans of the Second World War at the Canadian War Museum. [Stephen J.Thorne]

“It gives me great satisfaction to see that, thanks to the support of the Mons authorities, the Canadian artillery gun that fired the last shells of the war can be presented here today,” he said. “Our commemorations enable us to recognize the past but also to become more aware of the vulnerability of the present. They invite us to experience life’s adversities without losing faith in humanity.”

Rifling (left) inside the muzzle of an 18-pound field gun that helped Canadian troops liberate the Belgian city of Mons. The dented brass wheel hubs help tell the story of the gun’s travels through the Somme, Vimy Ridge and Passchendaele. [Stephen J. Thorne]

Advertisement