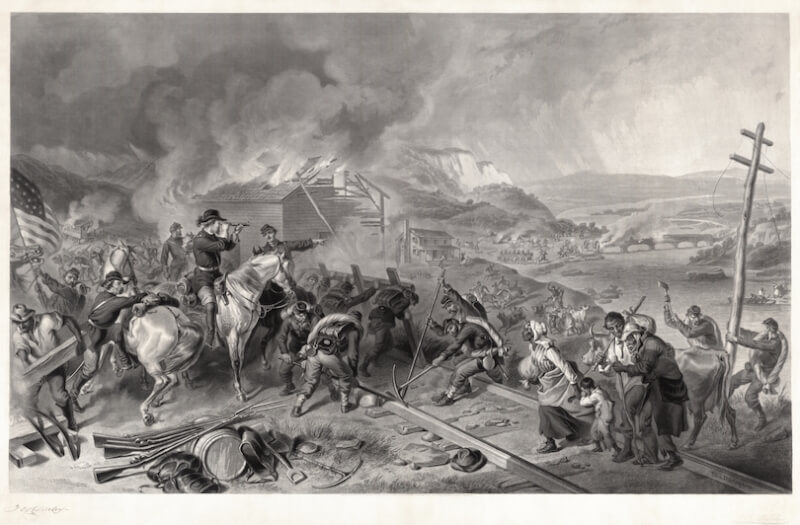

An 1868 engraving by artist Felix O.C. Darley depicts Sherman’s March to the Sea, an early example of total war in which the Union general led his 62,000-man army across Georgia to Savannah. Foraging off the countryside, they destroyed mills and cotton gins, confiscated livestock, looted homes and tore up more than 300 kilometres of rail lines.

[Felix O.C. Darley/Wikimedia]

Rules governing wartime conduct on the battlefield and beyond became a focus of discussion with the onset of the industrialized warfare of 1914-1918 and its mass killing capabilities—primarily the machine gun, poison gas, mobile artillery, tanks and airplanes.

Armies no longer lined up in open fields and commenced firing muskets and cannons at a mutually agreed-upon hour. The First World War was marked by unprecedented death and destruction, believed to be the first in which more civilians were killed than combatants—as many as 13 million to 9.7 million.

The International Encyclopedia of the First World War defines “atrocity” as an act of violence condemned by contemporaries as a breach of morality or the laws of war.

“’Atrocities’ are culturally constructed,” it says. “By 1914, an international discourse on ‘civilized’ war had defined ‘atrocities’ as acts perpetrated by an enemy that was ‘uncivilized,’ or ‘barbarian.’”

The sinking of the RMS Lusitania in May 1915, with its 1,198 primarily civilian deaths, is a Great War example of an atrocity that became an Allied propaganda tool and rallying cry. But it was far from the first atrocity of the conflict, and it wouldn’t be the last.

Between August and October 1914, the German army is known to have executed 5,521 civilians in Belgium and 906 in France. Ten or more were killed in 129 of the incidents.

“Most reports published by the official commissions of investigation set up by the Allied governments gave a correct picture of the nature and approximate extent of the violence,” says the encyclopedia. “The majority of the victims were men of military age, but a substantial minority were women and children.

“Civilians were used as human shields; and there were instances of wanton cruelty and widespread incendiarism. There were many accounts of rape, although the frequency of the crime is hard to assess.”

More damaging for Germany’s reputation as a cultured nation, it says, were the “cultural atrocities”—the shelling of the world-famous Reims Cathedral and the deliberate burning of the Louvain University Library, to name two.

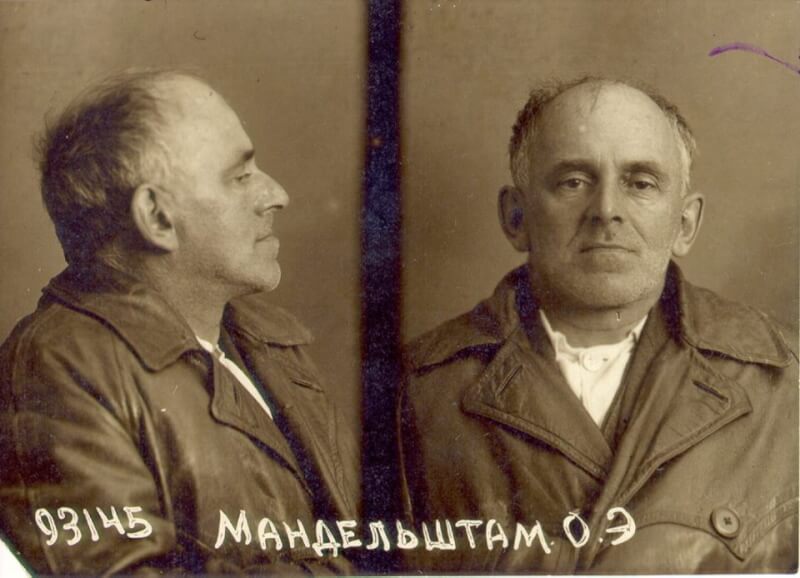

Regimes like Hitler’s and Stalin’s often make the fatal mistake of keeping exhaustive records of their crimes. This is a mugshot taken by The People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD) of Russian poet Osip Mandelstam taken in 1938 after his second arrest. He was sentenced to five years in a corrective-labour camp in the Soviet Far East and died at a transit camp near Vladivostok at age 47.

[Wikimedia]

War between modern, civilized nations, it was assumed, would be a different matter. The optimism proved wrong.

One assumes we are all well aware of enemy atrocities in both world wars. But atrocities are not the sole domain of evil empires.

While the scale of the Nazi-engineered Holocaust in 20th-century Europe and Japan’s brutal occupations of China, Korea and other parts of the Far East and South Pacific in the 1930s and ’40s are marked by unparalleled cruelty and death, Allied nations and their armies—including Canadian, British and American—have not always followed the conventions of the times, to put it mildly.

The history of genocide in the Americas by so-called civilized nations is well-documented, including the abominations of slavery and the eradication of the continents’ Indigenous Peoples. So, too, are the wrongs of the Colonial Era, during which British, French and Belgian practices in Africa, India and elsewhere were particularly egregious.

Eastern Europe, the Balkans especially, are notorious for their ethnically based wars and atrocities—pogroms, rape, genocide and attempted genocide among the practices staining the histories of an inordinate number of eastern European regions.

Public opinion in the West condemned the atrocities committed by virtually all sides in the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913, which were seen as barbaric deeds by backward peoples. War between modern, civilized nations, it was assumed, would be a different matter. The optimism proved wrong.

Poison gas was used liberally by all sides in the First World War, but it was an Ally—the French—who used it first, in August 1914. Chemical weapons only accounted for one per cent, or 91,000, of the war’s total deaths, but the fear factor was incalculable.

This despite the fact the use of “poison” in warfare had been banned by the Hague Convention of 1907, then again by the Geneva Protocol in 1925. Neither stopped their use.

The treatment of civilians and prisoners of war has been at the core of the laws of war since they were first formalized under the Lieber Code, authored by Prussian-American philosopher Franz Lieber and issued by U.S. President Abraham Lincoln on April 24, 1863.

It set out the rules of conduct for Union soldiers through the Civil War, and it remains the basis of most regulations of the laws of war for the United States. The document inspired other countries to adopt similar rules and was used as a template for international efforts in the late-19th century to codify the laws and customs of war.

Interestingly, the U.S. today does not subscribe to international law on many matters affecting the conduct of war. It is not, for example, a signatory to the Ottawa Convention on Cluster Munitions, which banned their use. The Americans are estimated to retain about a billion submunitions, or cluster bomblets.

The U.S. has even supplied Ukraine with the weapons, up to 40 per cent of whose munitions lie unexploded after delivery and pose a lethal danger to civilians—especially curious children—and property for years.

Soldiers of the U.S. Seventh Army summarily execute SS prisoners in a coal yard at Germany’s Dachau concentration camp on April 29, 1945.

[U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum/National Archives and Records Administration, College Park]

“The men were not looking for prisoners, and considered a dead German was the best.”

During the 144-day Battle of the Somme, around the time they took the French village of Courcelette from the Germans in September 1916, Canadian soldiers stopped taking prisoners. Surrendering Germans relegated to the rear of the Allied formations, had developed a habit of picking up downed weapons and shooting their captors in the back, so the Canadians played it safe and killed them outright instead.

Lieutenant-Colonel Elmer W. Jones wrote that during the offensive some enemy “offered to surrender but in most cases these men were bayoneted by our advancing [Canadian] troops.”

“The men were not looking for prisoners, and considered a dead German was the best,” Major-General Richard Turner wrote in his diary.

Private Lance Cattermole of the 21st Battalion (Eastern Ontario) claimed that he and his comrades had been given strict instructions to take no prisoners until Canadian objectives had been achieved at Courcelette.

The battalion’s third wave was mopping up enemy positions when Cattermole observed a young German, “scruffy, bareheaded, cropped hair, and wearing steel-rimmed spectacles, [who] ran, screaming with fear, dodging in and out amongst us to avoid being shot, crying out ‘Nein! Nein!’

“He pulled out from his breast pocket a handful of photographs and tried to show them to us (I suppose they were of his wife and children) in an effort to gain our sympathy. It was all of no avail. As the bullets smacked into him he fell to the ground motionless, the pathetic little photographs fluttering down to the earth around him.”

The Canadians thus developed a reputation as brutally effective soldiers and projected an aura that inspired fear and respect in the enemy. Their image as ruthless fighters only grew during their time as shock troops after the 1917 victory at Vimy and through the Hundred Days Campaign to the end of the war.

The reputation persisted into the Second World War, and not without justification. The Canadians were good fighters—and remain so to this day—but, as with most armies, there were occasions when rules took a backseat, whether it was the spirit of getting the job done or simply retribution.

Members of The Lake Superior Regiment (Motor) pose with a Hitler Youth flag after the razing of Friesoythe, Germany, on April 16, 1945.

[Alexander Mackenzie Stirton/LAC]

Soldiers threw petrol cans into buildings along side streets and ignited them with phosphorus grenades.

In the war’s dying days, on the night of April 14-15, 1945, the 4th Canadian (Armoured) Division attacked the German town of Friesoythe. One of its battalions, The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada, captured it.

The battalion commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Frederick Wigle, was killed by a German soldier. Under the mistaken belief that he had met his demise at the hands of a civilian, the division commander, Major-General Christopher Vokes, ordered that the town be razed in retaliation.

“A first-rate officer of mine, for whom I had a special regard and affection, and in whom I had a particular professional interest because of his talent for command, was killed,” Vokes wrote in his autobiography. “Not merely killed, it was reported to me, but sniped in the back.

“I summoned my [head of the operations staff]. ‘Mac,’ I roared at him, ‘I’m going to raze that goddam town. Tell ’em we’re going to level the fucking place. Get the people the hell out of their houses first.’”

The officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Mackenzie Robinson, obeyed but persuaded Vokes not put the order in writing or issue a proclamation to the local civilians.

The Argylls had already begun burning Friesoythe in reprisal for their commander’s death. After Vokes issued his order, the town was systematically set on fire with flamethrowers mounted on armoured vehicles.

Soldiers threw petrol cans into buildings along side streets and ignited them with phosphorus grenades. The attack continued for over eight hours. Friesoythe was almost totally destroyed.

“The raging Highlanders cleared the remainder of that town as no town has been cleared for centuries, we venture to say,” wrote the commanding officer of the 1st Battalion, The Algonquin Regiment.

The war diary of the 4th Canadian Armoured Brigade records: “When darkness fell Friesoythe was a reasonable facsimile of Dante’s Inferno.”

Twenty German civilians died in the town and surrounding area. It would not be the only Allied atrocity in the closing days of the war.

Some 60 German cities were destroyed and more than a million civilians … were killed.

Allied bombers first hit Second World War Germany in 1940 after Hermann Göring’s Luftwaffe began raiding British airfields in preparation for an invasion of the British Isles. This, after Göring had declared that ‘no enemy bomber can reach the Ruhr. If one reaches the Ruhr, my name is not Göring. You can call me Meyer,” a reference to a common German name.

The first raid on Berlin, whose effect was more psychological than physical, provoked the Nazi leadership into hitting London—not once, but many times over the course of months. What became the London Blitz proved a costly mistake that shifted the tide of the Battle of Britain by giving the RAF time and space to reconstitute.

As the months passed, the bombing campaigns escalated. Both sides all but ignored the plight of civilians.

Americans began daylight raids in August 1942, convinced that with the aid of the sun and Norden bombsights, they could administer precision strikes on high-value targets and avoid excessive civilian casualties. They didn’t.

Air Chief Marshal Arthur (Bomber) Harris, architect of RAF Bomber Command’s nighttime campaign, which included Canadian and other Commonwealth crews, had no such qualms. He opted instead to prioritize his crews’ lives above all and essentially saturate their target areas with bombs.

Frustrated in their daylight efforts and losing planes and men at an alarming rate, the Americans would ultimately follow Harris’s lead and abandon any notion of precision strikes. In the Pacific theatre, they turned Japanese cities into mass infernos using napalm—a sticky, gasoline-based substance—for the first time, late in the war, to devastating effect.

The May 1943 Dambusters Raid by Lancasters of 617 Bomber Command Squadron, including 30 Canadians, breached two hydroelectric dams and caused catastrophic flooding in Germany’s industrial Ruhr Valley. Some 1,600 civilians were killed, at a cost of eight aircraft and 53 crewmen’s lives (14 Canadian), all to minimum advantage: German production was back on track by September.

At Dresden in February 1945, thousands of Allied bombers in streams hundreds of kilometres long and dozens wide dropped incendiaries for three days and nights, igniting and feeding firestorms that consumed the city and incinerated between 35,000 and 135,000 of Dresden’s occupants.

The onslaught over German cities that followed Göring’s boast inspired Germans to start calling air raid sirens “Meyer’s trumpets.”

But the results were no joke. Some 60 German cities were destroyed and more than a million civilians—the bulk of whom did, after all, work the factories and tolerate, if not actively support, the Nazi regime—were killed by Allied bombs.

Japanese deaths in the American raids on the Pacific home islands, which ramped up after B-29s began staging out of the captured Marianas in November 1944, have been estimated at between 241,000 and 900,000.

The atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki followed, made possible by uranium first refined by Eldorado Mining and Refining Limited at Port Hope, Ont.

Berlin’s two main hospitals estimated the number of rape victims in the German capital alone at 95,000 to 130,000.

Before, during and for some time after the conflict, Allied leaders—Churchill, Roosevelt and, later, Truman—looked the other way while Josef Stalin had a million of his own people executed and sent millions more into forced labor, deportation, famine, massacres and detention and interrogation.

The Soviet leader’s Red Army soldiers were notorious for brutality during their push westward into Germany in 1945, driven by a deep-seated hatred for fascists and payback for the merciless toll the Wehrmacht took on the Soviet citizenry after Hitler ordered the invasion of the USSR in 1941.

To the Red Army’s ultimate detriment, women bore the brunt of the retribution, which served only to deepen the Reich’s resolve and stiffen its resistance in the east.

“Red Army soldiers don’t believe in ‘individual liaisons’ with German women,” the playwright Zakhar Agranenko wrote in his diary while serving as an officer in East Prussia. “Nine, 10, 12 men at a time—they rape them on a collective basis.”

Natalya Gesse, a close friend of the scientist Andrei Sakharov, observed the Red Army in action in 1945 as a Soviet war correspondent. “The Russian soldiers were raping every German female from eight to 80,” she recounted later. “It was an army of rapists.”

Historian Antony Beevor reports that Berlin’s two main hospitals estimated the number of rape victims in the German capital alone at 95,000 to 130,000. “One doctor deduced that out of approximately 100,000 women raped in the city, some 10,000 died as a result,” mostly of suicide, he wrote in his 2002 book Berlin: The Downfall 1945.

German troops who surrendered on the eastern front—three million of them—were summarily shot or marched off to remote Soviet labour camps, many never to see their homes or families again. Almost 1.1 million died in captivity, according to German historian Rüdiger Overmans.

Yet, it was only after the Cold War took root in 1947 that Western democracies began citing the evils of Communist rule in earnest.

“You have to have men who are moral, and at the same time, who are able to utilize their primordial instincts to kill without feeling.”

More recent wars have had their own atrocities. Between 1965 and 1975, American and allied aircraft dropped more than 6.8 million tonnes of bombs on Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia—twice that dropped on Europe and Asia combined in the Second World War. Pound for pound, it remains history’s largest aerial bombardment.

At My Lai in March 1968, U.S. Army Second Lieutenant William Calley led his platoon into the South Vietnamese village and, despite the fact no enemy were present, ordered his men to kill all its residents; 22 unarmed civilians died.

Calley was convicted of 22 counts of premeditated murder and, at the behest of President Richard Nixon, was released to house arrest three days after his conviction. He served three years.

In the Francis Ford Coppola movie Apocalypse Now, the character of Colonel Walter E. Kurtz, played by Marlon Brando, relates the tale of a horrific incident, presumably carried out by the Viet Cong, and lauds the will of such men who “fought with their hearts, who have families, who have children, who are filled with love…that they had the strength, the strength to do that.”

“If I had 10 divisions of those men, then our troubles here would be over very quickly,” he said. “You have to have men who are moral, and at the same time, who are able to utilize their primordial instincts to kill without feeling, without passion. Without judgment. Without judgment. Because it’s judgment that defeats us.”

In the final year of the U.S. Civil War, Union General William Tecumseh Sherman led the March to the Sea through Georgia and the Carolinas, which sounded the death knell to the Confederacy’s bid for independence—and slavery.

Along the way, his armies laid waste not only to military stockpiles, bridges and railroads, but to homes, farms and livestock—civilian infrastructure—in a calculated campaign to break Southerners’ will to fight.

In a Christmas Eve 1864 letter to his chief of staff, Sherman wrote that the Union was “not only fighting hostile armies, but a hostile people, and must make old and young, rich and poor, feel the hard hand of war, as well as their organized armies.”

In April 1865, Sherman accepted the surrender of all the Confederate armies in the Carolinas, Georgia and Florida. His tactics would come to form the core of the philosophy known as “total war.”

The phrase “total war” is believed to have been coined in 1935 by German general Erich Ludendorff in his memoir, Der totale Krieg [‘the total war’]. It deems any and all civilian resources and infrastructure as legitimate military targets, mobilizes all of a society’s resources to fight, and prioritizes warfare above all else.

U.S. Air Force General Curtis LeMay adapted the concept in 1949, when he proposed that a total war in the nuclear age would consist of delivering the entire nuclear arsenal in a single overwhelming blow, going as far as “killing a nation.”

Fortunately for the planet, the concept of mutual assured destruction—or MAD—has so far kept the nuclear genie in the bottle.

Advertisement