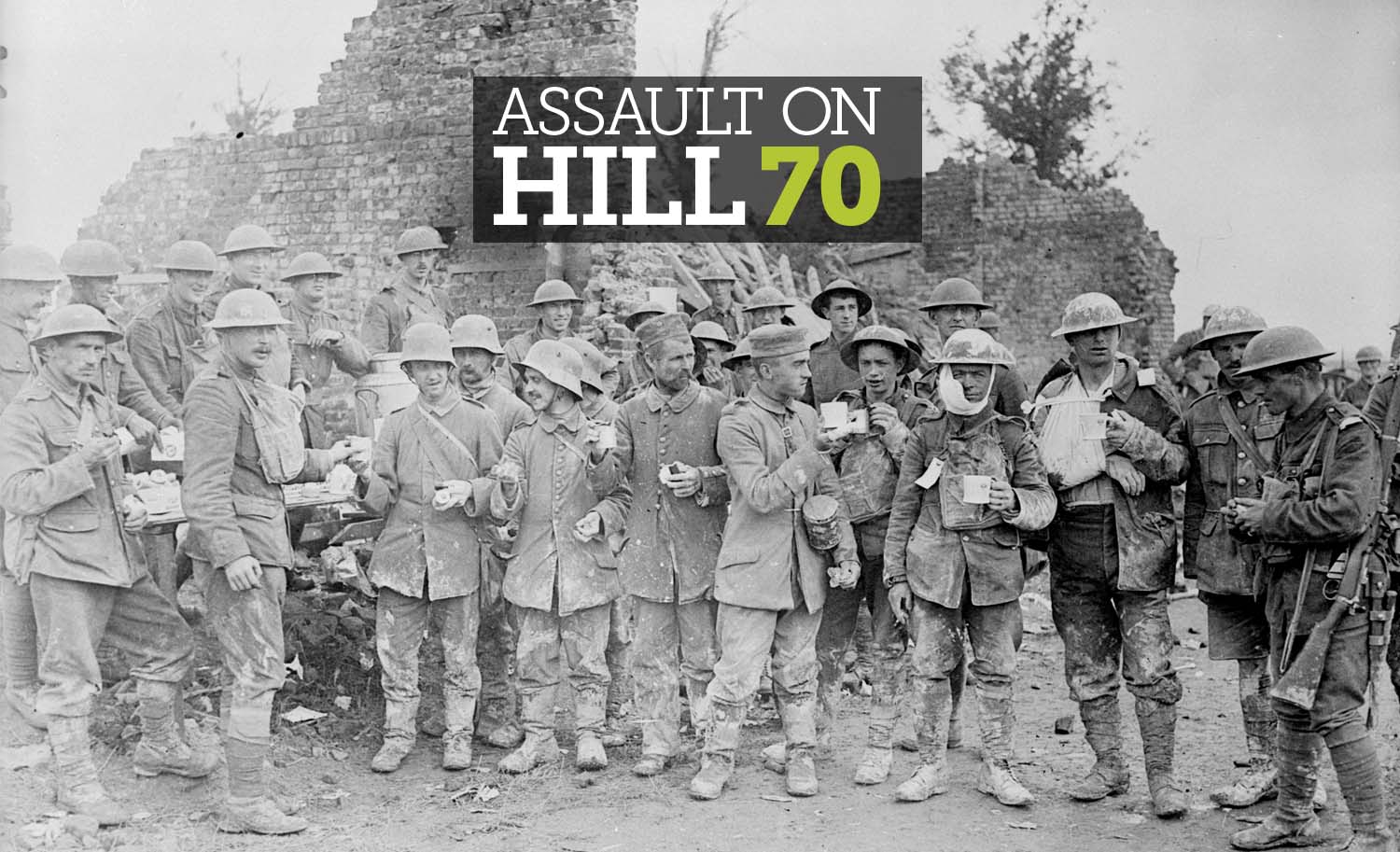

[Pause in the action — Canadian soldiers and German prisoners receive coffee and biscuits from a YMCA hut less than a kilo-metre from the front line in 1917. The bitter fight for Hill 70 included vicious hand-to-hand combat and German counterattacks using mustard gas and flame-throwers.]

No, it’s not Vimy Ridge, Canada’s most celebrated battle, but rather the attack on Hill 70, near the northern edge of the French coal mining town of Lens, barely 10 kilometres up the road from Vimy.

The name Hill 70 refers to the feature’s height in metres above sea level. In 1917, it was a gradually rising, chalky, treeless slope about half Vimy’s height and less than half its length. It had been in German hands since 1914 and it was well fortified.

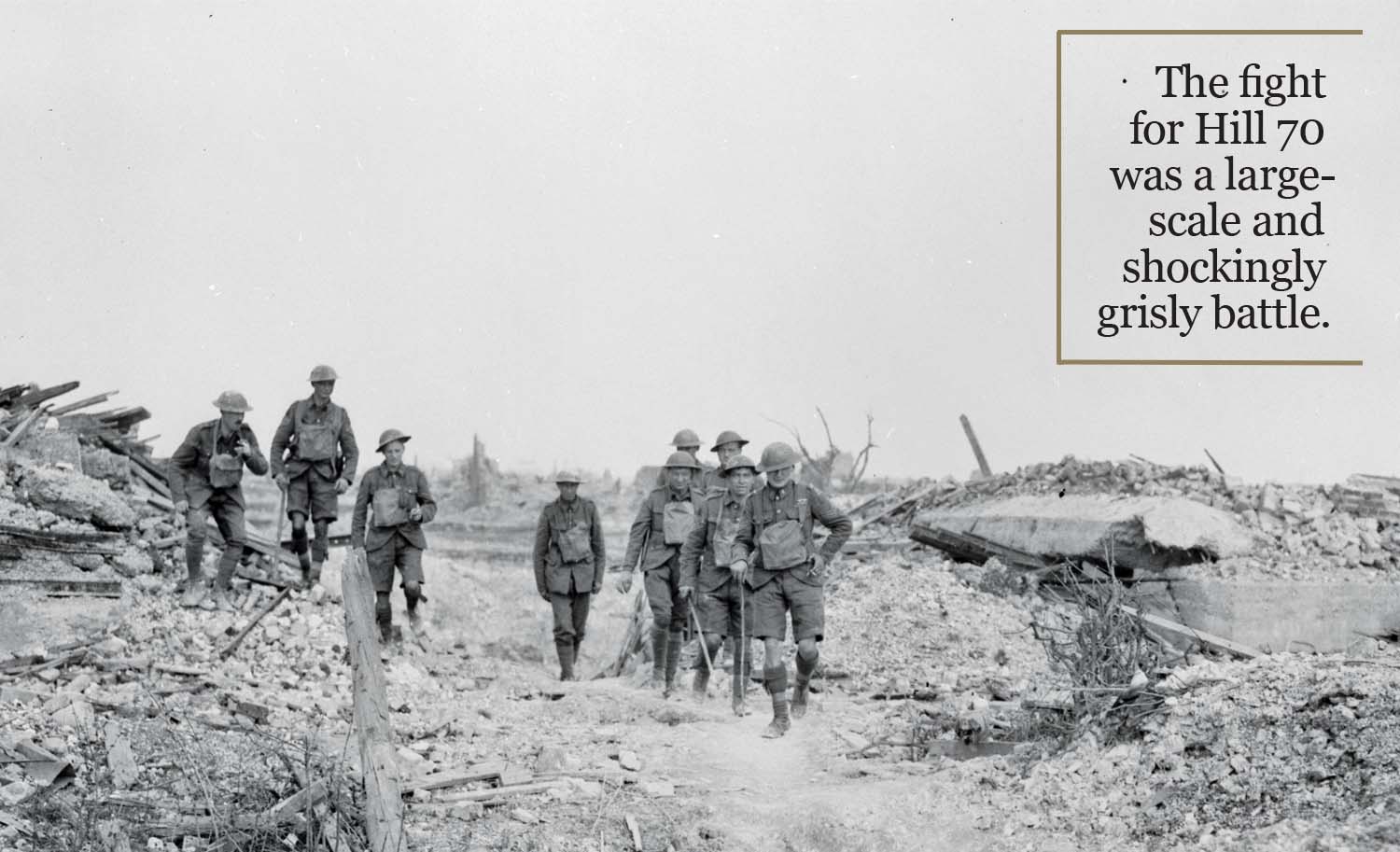

The fight for Hill 70 in August 1917 was a large-scale and shockingly grisly battle, considered an epic Canadian victory by contemporaries. Yet, a century later, the battle has been largely forgotten. The men of the famed Canadian Corps who fought in the bloody engagement at Hill 70 deserve better.

The first major post-Vimy attack by the Canadian Corps proved a striking tactical victory in support of a broader strategic purpose. The immediate goal of the assault was to seize the dominating high ground north of German-occupied Lens, oblige the enemy to withdraw, and threaten its control of Lille, a major transportation centre. More importantly, the Canadian attack was intended to pin down German forces around Lens and draw others away from the major British offensive in Flanders, which began on July 31. The Canadian attack was also intended to cause severe German casualties, the replacements for which would be unavailable for deployment to Flanders.

In June, Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur Currie had become the first Canadian promoted to the command of the Canadian Corps. The attack on Hill 70 would be his first major operation in that position. On July 7, his immediate superior, British General Sir Henry Horne, commander of First Army, instructed Currie to prepare plans for the seizure of Lens, a shattered urban landscape of wrecked brick houses and barely recognizable streets surrounded by a labyrinth of slag heaps and destroyed mining installations, rail sidings and buildings.

It was understood that capturing Lens against the tenacious, well-concealed and dug-in defenders would prove difficult and undoubtedly very costly. Currie personally reconnoitered and studied the terrain. It made little sense to the seasoned Canadian commander to attack Lens without first seizing Hill 70, since the Germans otherwise would observe the Canadians’ advance into Lens and direct devastating artillery fire on them. The town would become a deathtrap.

Currie boldly and successfully petitioned Horne for the seizure of Hill 70 instead of Lens itself, expecting the Germans to withdraw from the town once this dominating feature was in Canadian hands. Currie planned to fortify Hill 70 right after its capture, knowing that the enemy’s doctrine of instantaneous counter-attacks would provide an opportunity to inflict massive casualties on them with concentrated artillery and machine-gun fire.

Canadian and British planning staff worked to identify objectives and readied the assault, while training and rehearsals with battlefield models familiarized officers and men with every aspect of the plan. Ammunition was moved to the gun lines and supplies of every kind were brought forward by trucks and narrow-gauge rail lines, which snaked their way as close to the front as possible. Heavy rain and Currie’s insistence on careful preparation delayed the attack until Aug. 15, probably beyond the time when it would make the most effective diversion from the Flanders offensive.

[Walking wounded — Members of a Canadian Scottish battalion near the front during the Battle of Hill 70 in August 1917. The 10 days of combat cost Canada 8,677 casualties, a quarter of them fatal.]

In the days before the attack, nearly 500 Canadian and British guns fired almost 800,000 shells, which steadily degraded German defences, cut barbed wire, hampered communications and collapsed trenches. Counter-battery fire knocked out 40 of 102 identified German artillery emplacements in positions that would disrupt the assault. Heavy guns and howitzers unleashed a deeper bombardment to disrupt German artillery and saturate rear-area enemy troop concentrations. This, combined with indirect fire from 160 Vickers machine guns, inflicted thousands of casualties on the Germans. Millions more machine-gun rounds would be fired during the battle itself. The Royal Engineers delivered 3,500 drums of burning oil and 900 gas shells into Lens, creating havoc and, just prior to the assault, causing a massive smokescreen.

Currie’s plan was to attack with two of his four divisions on a roughly 3,700-metre front to a depth of 1,400 metres, hurling the enemy back from Hill 70. Three objective lines guided the Canadian assault: first was the German front-line trenches on the forward slope, second was the crest of the hill, and third was low on the reverse side.

At 4:25 a.m., just before dawn over a hellish, shell-cratered landscape, the uphill attack began. More than 200 18-pounder field guns and 48 4.5-inch howitzers launched a dense creeping barrage of fire and steel to shield the advancing Canadians. The 1st Canadian Division, on the left, attacked Hill 70 proper; the 2nd Division on the right swept along its southern slope and through the ruins of some industrial suburbs of Lens. Each division attacked with two brigades forward, the initial assault force comprising 10 battalions—about 7,000 men—reinforced and leapfrogged by other battalions as the attack progressed. Simultaneously, the 4th Division’s 12th Brigade launched a feint attack against the southern perimeter of Lens, which successfully drew German artillery fire away from the main battle at Hill 70.

In his diary, Arthur Lapointe of the 2nd Division’s 22nd Battalion described the assault: “Zero hour! A roll as of heavy thunder sounds and the sky is split by great sheets of flame…. I scramble over the parapet and…am one of the first in no man’s land…. The noise of the barrage fills our ears; the air pulsates, and the earth rocks beneath our feet…. We reach the enemy’s front line, which has been blown to pieces. Dead bodies lie half buried under the fallen parapet and wounded are writhing in convulsions of pain.”

Even though the Germans had accurately predicted the time and location of the attack, many first-line objectives were captured in a mere 20 minutes. But the speed of the advance belies the ferocity of the fighting. Some men reached the second line about one hour after setting out, while others had already pushed to their third-line objectives. Some German positions held out stubbornly and casualties mounted as Canadian troops stormed machine-gun positions, seized stoutly defended shell craters, or picked their way through urban rubble.

As soon as the first objectives were secured, fatigue parties brought up ammunition, entrenching tools and supplies, signal linesmen laid wire to the new positions, and stretcher-bearers working in dangerously exposed positions evacuated the wounded.

One of them, Irish-born Private Michael O’Rourke from the 7th Battalion, brought out wounded men almost constantly for 72 hours, despite nearly being killed by shell bursts at least three times. O’Rourke received the Victoria Cross, one of six awarded to Canadians at Hill 70 and Lens.

The Canadians swiftly built defences by repairing captured German trenches and reversing the direction of the firing steps and parapet. They set up barbed wire and filled thousands of sandbags on the new front, and dug strongpoints in the chalky ground in carefully sited positions for 48 Vickers guns and as many as 200 Lewis light machine guns.

The Germans mounted four counter-attacks early that morning, and with the help of accurate massed Vickers and artillery fire, each was repulsed with heavy German losses. The artillery was directed by observation officers atop Hill 70, using field telephones and, a first for the Canadian artillery, wireless radio. The Germans were decimated.

“Our gunners, machine-gunners and infantry never had such targets,” Currie wrote in his diary. It was a “killing by artillery,” recounted Lieutenant-Colonel A.G.L. McNaughton, the Canadian senior counter-battery officer.

But the Germans kept coming. They threw in seven reserve battalions from two divisions, including the crack 4th Guards Division, joining the eight battered battalions already facing the Canadians. By the end of the battle’s first day, the Canadians had suffered 1,056 killed, 2,432 wounded and 39 taken prisoner.

The enemy pressure was nearly unbearable: for the next three days, the Germans counterattacked in various strengths and at different locations along the Hill 70 front. They doubted their ability to retake the hill early on, but at least their counterattacks destabilized the Canadians and prevented further advances. This bitter fighting was perhaps the most vicious hand-to-hand combat experienced by Canadians during the war, involving small arms, grenades, bayonets, clubs, fists and anything else that was handy. The Germans also deployed a terrifying new weapon: the flame-thrower.

No quarter was given by either side during these grim days. A few of the German attacks resulted in temporary gains, but all 21 of them were defeated. The Canadians suffered a further 1,800 casualties from Aug. 16 to 18, but Hill 70 remained theirs.

Adding to the misery, the battlefield was dangerously toxic, thanks to both sides’ liberal use of poison gas. Not previously used against the Canadians, the German mustard gas, so-called due to its odour, was especially gruesome. It blinded, burned lungs and hideously blistered and deformed flesh. Even those Canadians behind the lines were not immune: the Germans fired some 15,000 gas shells, mainly mustard gas, attempting to disrupt the devastating Canadian artillery fire. When the Canadian gunners donned their awkward gas respirators with foggy eye pieces, they were unable to properly lay the guns or quickly respond to appeals for support. Many in the gun lines removed their gas masks and 183 gunners became casualties. Theirs were among the most heroic actions of the 10-day struggle for Hill 70 and Lens.

[Aftermath — Canadians pass destroyed German gun pits on the western outskirts of Lens, France, in September 1917. German forces held the bombarded town until their final retreat in 1918.]

Currie should have quit while he was ahead, but he wanted the Germans out of Lens as planned. A lull of several days ended on Aug. 21, when the 4th Division, with the 2nd in support, launched a probing attack into the southern and western outskirts of Lens. The attack was a worthwhile attempt to convince the Germans to evacuate the town. But the 4th Division’s staff work was rushed and incomplete and its attacks hasty and poorly judged. This marred Currie’s enormous success at Hill 70, and the Canadian commander himself must shoulder the blame.

Weathering a heavy artillery barrage, the Germans remained alert and shelled the Canadians’ start line with devastating effect. Then they launched a spoiling attack of their own. The two sides met in no man’s land and another fierce hand-to-hand struggle erupted in the pre-dawn gloom. Without much cover, losses climbed rapidly and the Canadians were obliged to break off the attack. Few objectives were gained, and because of the urban and industrial rubble, it was difficult to dig in and consolidate even these. German machine guns decimated British Columbia’s 47th Battalion in the shattered urban landscape.

It should have ended there, but in the early hours of Aug. 23, a haphazardly planned night assault by Manitoba’s 44th Battalion against a heavily defended slag heap known as the Green Crassier proved disastrous, with German artillery and machine guns exacting a very heavy toll in Canadian lives. Against all odds, the resolute Canadians managed to scale the Green Crassier, but they could not hold it against sustained German counterattacks. The 44th suffered 257 casualties, nearly half of its strength. Minor operations on Aug. 25 ended the battle for Hill 70 and Lens. The entire fight, from Aug. 15 to 25, cost 8,677 Canadian casualties—5,400 at Hill 70 and 3,300 at Lens. There were nearly as many Canadian casualties during the 10-day battle for Hill 70 and Lens as at Vimy, although fewer men were involved. German casualties are estimated at 12,000 to 15,000.

No German forces left Lens and some reserve forces were sent there rather than be dispatched to Flanders. The Germans considered the Canadians the best assault force available to the British and admitted that at Hill 70 “the Canadians had attained their ends” and that the “plan for relieving the troops in Flanders had been upset.” Still, Lens remained in German hands.

Hill 70 had been a brilliant tactical victory and a partial strategic success. Field-Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, commander of the British Expeditionary Force, recalled Hill 70 as “one of the finest minor operations” of the entire war, while Currie recalled it as the Canadians’ “hardest” battle to that point but a “great and wonderful victory.”

Press accounts in Canada in August 1917 hailed Hill 70 as comparable to Vimy in achievement and significance. A Calgary Daily Herald headline on Aug. 17 blared: “Hill 70 Runs Red Today with Blood of German Army.”

The battle’s resonance with Canadians has been long overshadowed by Vimy. The only memorial in Canada recalling the Canadians’ deeds at Hill 70 is a modest monument and park that was laid out in the eastern Ontario hamlet of Mountain in 1925. In recent years, it was rededicated and renovated. But on Aug. 22, the Hill 70 Memorial Project, a Canadian charity, plans to unveil a dramatic, privately funded obelisk in a beautifully landscaped setting straddling the 1917 start line at Loos-en-Gohelle, France. The Battle of Hill 70 will finally get the recognition it has long deserved.

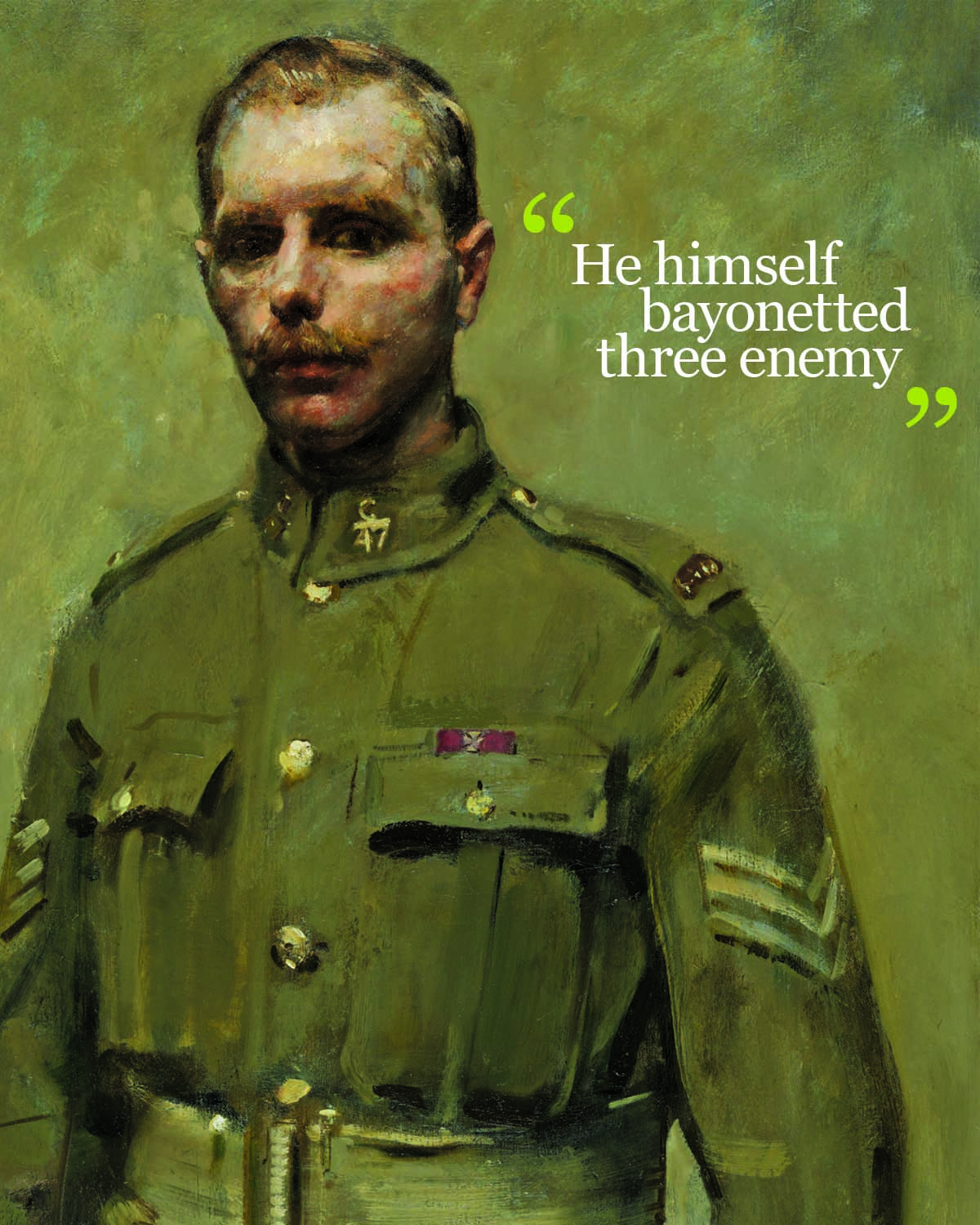

[For bravery Ukrainian-Canadian soldier Filip Konowal received the Victoria Cross after mopping up cellars, craters and machine-gun emplacements. He killed at least 16 enemy soldiers.]

Six Victoria Crosses were awarded to Canadians who fought at Hill 70 and Lens, two more than at Vimy.

A 29-year-old Ukrainian immigrant to Canada, Filip Konowal had previously served as a bayonet and hand-to-hand fighting instructor in the Imperial Russian Army. He arrived in Canada in 1913 and worked as a logger in British Columbia. He enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force in 1915 and served overseas in the Canadian Corps with British Columbia’s 47th Battalion. He served at Vimy Ridge in April 1917 and distinguished himself in the fighting at Lens on Aug. 22-24.

Acting Corporal Konowal gallantly led his section of men in fighting among the shell craters and shattered houses, fiercely attacking several German machine-gun posts and killing their crews. His Victoria Cross citation reads, in part: “In one cellar, he himself bayonetted three enemy and attacked single-handed seven others in a crater, killing them all…. This non-commissioned officer alone killed at least sixteen of the enemy, and during two days’ actual fighting carried on continuously his good work until severely wounded.”

Following the war, Filip Konowal settled in Hull, Que., and died in 1959, at the age of 70.

The other five VC recipients are:

• Private Harry Brown of the 10th (Canadian) Battalion

• Company Sergeant-Major Robert Hill Hanna of the 29th (Vancouver) Battalion

• Sergeant Frederick Hobson of the 20th (Central Ontario) Battalion

• Acting Major Okill Massey Learmonth of the 2nd (Eastern Ontario) Battalion

• Private Michael James O’Rourke of the 7th (British Columbia) Battalion

Advertisement