She Wears the Bletchley Medal, 2019. [Elaine Goble/Beaverbrook Collection of War Art/Canadian War Museum, 20190297-002]

Veterans are the focus of her life’s work.

“Everybody has a story to tell,” said Goble, whose paintings and drawings are currently on exhibition at the Canadian War Museum. “What story is more compelling than one that is looking at a person alive in my own community who has been informed by a legacy of conflict?”

Working from interviews—usually several per subject—and her own photographs (she was once an assistant to well-known Canadian photographer Malak Karsh), Goble delves into the experiences of her veteran muses, infusing each laborious work with detail and symbolism.

The lines on Favel’s face are like a roadmap of his life.

A painting can take months. From the mixing to the application, just working with egg tempera—an ancient process using egg yolks hand-mixed with pigments and water—is painstaking: “No person in their right mind would sit with a small sable paintbrush and do a large painting in egg tempera,” she said.

The results are extraordinary. Her most recent painting is of Indigenous D-Day veteran Philip Favel. Entitled “Normandy Warrior,” it is vivid yet subtle in its light and expression, his eyes gazing straight at the viewer as if he were right there with them.

Normandy Warrior, 2020. [Elaine Goble/Beaverbrook Collection of War Art/Canadian War Museum, 20200359-001]

Favel…fought for equal compensation for Indigenous veterans after the war.

“There is such a connection while I paint between the medals and their faces, their bodies,” said Goble. “Their features accommodate and meld in with their history in the medals. It’s almost like they’re linked in the painting itself.

“If I just painted a portrait, I wouldn’t feel a connection between what they were wearing, what they were carrying, what symbols. It wouldn’t mean anything. But as soon as it is a veteran, or a keeper of history, every detail becomes interlinked with who they are.”

Favel, a Cree from Sweetgrass First Nation in Saskatchewan, fought for equal compensation for Indigenous veterans after the war and served as Grand Chief of the Saskatchewan First Nations Veterans Association. He was painted at age 98 and died in January 2021, a few months after the piece was unveiled as a permanent part of the museum’s Beaverbrook Collection of War Art.

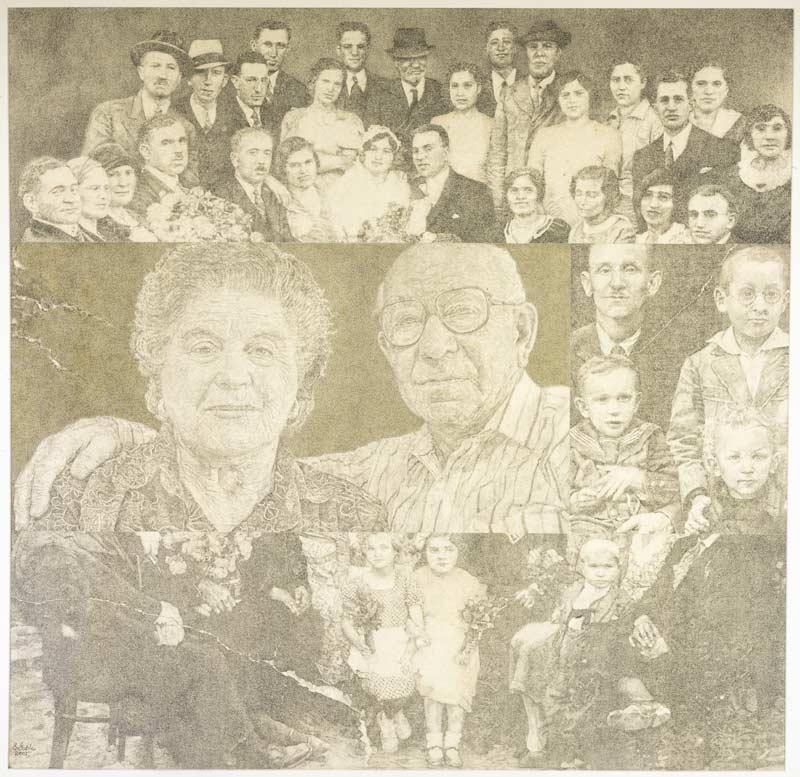

Goble’s graphite works include “After the Holocaust – A Family Album,” actually a graphite-and-egg tempera montage on paper, featuring illustrations of Holocaust survivors Valerie and Mendel Good surrounded by period images of long-lost family.

After the Holocaust — A Family Album, 2001. [Elaine Goble/Beaverbrook Collection of War Art/Canadian War Museum, 20010243-003]

“The second an artist is finished, a painting takes on a life of its own.”

Goble has no favourite piece.

“It’s not what I think of them,” she said. “It’s what they think of them when they look at the finished product.

“The second an artist is finished, a painting takes on a life of its own, and it belongs to the person who looks at it—whether it’s for five seconds or five hours. If it’s possible, I want the painting to just be on its own. Like, 50 years from now, it doesn’t need an artist to hold its hand; it just needs the history behind it.”

Other pieces include a fighter pilot who lost his voice but not his big personality, a wireless telegraphist who intercepted signals from U-boats and later advocated for equal rights for women in the military, and a female impersonator who performed for the troops as a member of the Canadian Army’s “Tin Hats” entertainment group.

The museum describes her work as “direct, realistic and unsentimental.” Goble’s details, it says—whether a satchel, a medal or a missing limb—bring attention to the memories and trauma of war.

“Elaine Goble’s portraits testify to the physical, psychological and emotional impacts of conflict in deeply personal ways,” said Caroline Dromaguet, interim president and CEO of the Canadian Museum of History and the war museum’s director general.

“Though most of the subjects are from the Ottawa area, their personal experiences are reflective of the experiences of many Canadians from other parts of the country.”

Portrait of Gwen, 2018. [Elaine Goble/Beaverbrook Collection of War Art/Canadian War Museum, 20190297-003]

Born in 1956 in St. Thomas, Ont., Goble studied fine arts at York University, then completed a Bachelor of Arts degree at Western University before moving to Ottawa in 1979.

Her works have been exhibited in dozens of museums and other venues and are in numerous permanent collections.

In 2005, Goble was commissioned by the Royal Canadian Mint to design the 25-cent commemorative coin for the Year of the Veteran. It depicts a male and female veteran from different generations.

Goble is therefore used to success and high-profile exposure for her work, but she is nevertheless grateful and humbled that she was able to “marry those two things that I hold precious together: a portrait of someone who lives in Canada with a legacy of war—to marry that with our hallowed museum, our war museum, that’s all I want. The artist can just step out of the way.”

She is equally “relieved that I did for the people in the portraits what I promised I would do…I would do their portraits and I would put them forth where I thought they had a permanent home.

“There were no guarantees and I was never asked for guarantees,” she added. “I’m so happy for those families who [attended the opening]. There were extended families looking at their loved ones on walls and that made me feel relieved.”

The 14 portraits comprising “Homage – The Art of Elaine Goble” are on display through Dec. 12 in the museum’s North Corridor. Visitors are encouraged to book their tickets in advance. For more information, visit warmuseum.ca.

Advertisement