Korean War veteran Ted Zuber depicts a resupply flight passing over members of the 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, in 1951. [Ted Zuber/CWM/19900084-001]

Ask many a Korean War veteran what they remember most about their time near the 38th parallel and they’re as likely as not to tell you something about topography, sweltering heat or bitter cold.

Ask the 1,500 men of the 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (3 RAR), and 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (2 PPCLI), what they remember most, and those still living will likely take you back to the peaks overlooking the picturesque Kapyong Valley.

It was there, on the road to Seoul, that the 118th Division of the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army (PVA) launched the main element of its spring offensive in April 1951.

The Canadians and the Aussies were at the tip of the defensive spear, poised to bear the brunt of the three-day onslaught by up to 20,000 Chinese soldiers. Today, the battle is widely regarded as the most significant action fought by either allied army in Korea, and Canada’s most famous battle since the Second World War.

Chinese casualties had begun to rise under relentless artillery strikes ordered by the supreme Allied commander on the peninsula, newly appointed U.S. General Matthew B. Ridgway.

The momentum of the war was shifting, and Kapyong was a lynchpin.

South Korean troops were establishing positions at the northern end of the Kapyong Valley when the PVA’s 118th and 60th divisions launched a local offensive at 5 p.m. on April 22.

Facing pressure all along the front, the South Koreans soon gave ground and broke, abandoning weapons, equipment and vehicles as they streamed southward out of the mountains.

Men of 2 PPCLI conduct a patrol on March 11, 1951. [Bill Olson/LAC/SF-820]

By 11 p.m., the South Korean commander had lost all communication with his units. At 4 a.m. the next day, supporting New Zealand troops were withdrawn, only to be sent back, then withdrawn again by dusk. The South Korean defences had collapsed, and on their way out they let the Canadians know the Chinese were coming.

“It was then, about mid-afternoon, that the rumour of the collapsing front acquired a meaning,” Captain Owen R. Browne, officer commanding ‘A’ Company, wrote in 2 PPCLI’s regimental journal.

“From my arrival until then both the main Kapyong Valley and the subsidiary valley cutting across the front had been empty of people. Then, suddenly, down the road through the subsidiary valley came hordes of men, running, walking, interspersed with military vehicles—totally disorganized mobs. They were elements of the 6th ROK (Republic of Korea) Division which were supposed to be ten miles forward engaging the Chinese. But they were not engaging the Chinese. They were fleeing!

“I was witnessing a rout,” continued Browne. “The valley was filled with men. Some left the road and fled over the forward edges of “A” Company positions. Some killed themselves on the various booby traps we had laid, and that component of my defensive layout became worthless….

“We knew then that we were no longer 10-12 miles behind the line; we were the front line.”

Some 40 million people died in the First World War; at least 70 million in the Second. By the time Soviet-backed North Korean forces crossed the 38th parallel into South Korea on June 25, 1950, folks didn’t want to hear any more about war.

And, so, when a U.S.-led United Nations coalition stepped in on the Korean peninsula, President Harry S. Truman and Prime Minister Louis St-Laurent called it a “police action,” an “intervention.”

The terms didn’t sit well with those who were there.

“There were 516 [Canadian] military guys dead over there,” George Guertin, a radio operator aboard HMCS Huron at the time, told Legion Magazine.

“I don’t call that a ‘police action.’ Just an ugly little war.”

In fact, no war was ever declared, and for the next 40 years or so those happenings on the Korean peninsula were officially referred to as “the Korean Conflict.” There was a Cold War, all right, but God forbid another hot one.

To most all but those who fought it, Korea was “The Forgotten War.”

In Canada, the combatants weren’t formally recognized as war veterans until the late 1980s, when Ottawa decided the war was, in fact, a war. And it wasn’t until 1991 that veterans were awarded Korean War service medals.

Seven years later in the U.S., which provided the bulk of resources to the war effort, President Bill Clinton signed Public Law 105-261, Section 1067, which declared the “Korean Conflict” would henceforth be called the “Korean War.”

Semantics? No. The change had ripple effects throughout the coalition of countries that made up the UN force in Korea. It influenced such things as pensions and compensation for veterans, including the 26,791 Canadians who served.

Groups such as the Korea Veterans Association of Canada, which wasn’t formed until the 1980s, stepped up efforts to get vets the support they needed—and deserved. With numbers dwindling, the group folded in 2021 and was replaced by the more centralized and descriptive Korean War Veterans Association of Canada.

The recognition deeply affected many who had long felt their service had been taken for granted, if it had been recognized at all. While Vietnam War veterans would return to America to a hostile anti-war welcome in the 1960s and early ’70s, Korean War veterans of the 1950s got almost no public reception whatsoever.

Korea vets endured passive hostility in the form of veterans’ organizations that refused to recognize their service, resisted incorporating the Korean War on cenotaphs and generally belittled their contributions, all while overlooking the fact that about 16 per cent of all those who served in Korea also served in the Second World War. They knew what war was, and what occurred on the Korean peninsula between June 25, 1950, and July 27, 1953, was by all first-person accounts a war.

“United Nations mountain warriors won their spurs today, holding their front and refusing to budge even though outflanked and encircled.”

Vernon Burke of 2 PPCLI checks Chinese trenches.[Bill Olson/LAC/SF-840]

Colonel James Riley Stone, 2 PPCLI commanding officer, eats cold beans while directing action from his tactical headquarters. [Bill Olson/LAC/SF-1289]

And the Patricias were decidedly in it.

With the disconcerting prospect of a superior force closing fast and ROK troops still pouring past them, the Canadians started digging trenches and positioning themselves on Hill 677 and along the 1.5-kilometre ridge connected to it.

They were on the west side of the Kapyong River. On the other side of 677, atop Hill 504, were the Aussies, dug in and ready for a fight.

The New Zealand 16th Field Regiment was in artillery support, with troops of the British 1st Battalion, Middlesex Regiment, at the rear along with three platoons of the U.S. 72nd Heavy Tank Battalion—15 tanks—alongside the main road that split the valley.

“No retreat, no surrender,” the Patricias’ British-born commander, Colonel James Riley Stone, told his men.

The Chinese struck 504 first, engaging the Aussies of 3 RAR, infiltrating the brigade position, then hitting the Canadian front.

“They’re quiet as mice with those rubber shoes of theirs and then there’s a whistle,” said Sergeant Roy Ulmer of Castor, Alta. “They get up with a shout about 10 feet from our positions and come in.”

Waves of massed Chinese troops sustained the attack throughout the night of April 23. The Australians and Canadians were facing the whole of the Chinese 118th Division. The battle was unrelenting through April 24.

“The Chinese employed all their familiar battle procedures in the attack—whistles, bugles, a banzai chorus, concerted action on the word of command and massed assaults followed one another in swift succession,” reported Bill Boss of The Canadian Press. “This was familiar only by description for these United Nations troops who until now had fought mainly an advancing war against token resistance.

“Now it was grim reality.”

The fight devolved on both fronts into hand-to-hand combat with bayonet charges.

“The first wave throws its grenades, fires its weapons and goes to the ground,” explained Ulmer, who previously served as a company sergeant-major with The Loyal Edmonton Regiment during WW II.

“The country went from a war-torn, impoverished nation to a global industrial powerhouse in just two generations.”

“It is followed by a second, which does the same, and a third comes up. Where they disappear to, I don’t know. But they just keep coming.”

The Australians, facing encirclement, were ordered to make an orderly fallback to new defensive positions late on the 24th.

The Patricias were surrounded, too. “But they held,” wrote Boss.

Captain John Graham Wallace (Wally) Mills of Hartley, Man., a WW II veteran fighting his first action as a company commander, ordered his ‘D’ Company men into the slit trenches. Then the unit directed artillery and mortar fire on its own position several times during the early morning hours of April 25 to avoid being overrun.

“Guns and mortars rained hell on that hill from 2 a.m. to 6 a.m.,” Boss wrote, his censored copy of the day void of identifying specifics such as battalion and company.

“Torrents of hot metal fragments decimated the Chinese ranks,” said an account by The Loyal Edmonton Regiment Military Museum.

The Chinese kept hitting Ulmer’s position until 4 a.m. By then, the forward platoon had almost exhausted its ammunition.

“The sergeant hurled his bayonetted rifle like a spear at his enemy,” Boss reported. “While two gunners stood up and gave covering fire from the hip, the remainder withdrew—but only 50 yards. There the company continued the fight, dividing the remaining ammunition and holding out until the enemy pressure relented.

“I counted 17 dead Chinese within inches and feet of those troops today and approximately 50 graves of enemy buried in the heat of battle. There were uncounted enemy dead where an intended rear and flank attack was thwarted.

“Another company fought at close quarters against waves of Chinese troops. This company shot and grenade[d] the enemy until its ammunition ran out.”

As the sun rose, 2 PPCLI, cut off from the rest of the UN forces, still held Hill 677. The Chinese had withdrawn. Ten Canadian soldiers were dead and 23 wounded.

Australian losses were 32 killed, 59 wounded and three captured. The New Zealanders lost two killed and five wounded. Chinese losses were pegged at between 1,000 and 5,000 killed and many more wounded.

That morning, U.S. transport planes dropped food, water and ammunition to the exhausted Patricias.

“United Nations mountain warriors won their spurs today, holding their front and refusing to budge even though outflanked and encircled,” began Bill Boss’s April 25 wire service account of the battle, place-lined West Central Sector, Korea. “It was a knock-down, drag-out battle with wave after wave of Chinese Communists who did everything but drive them from their positions.”

Five Patricias received valour medals and 11 were Mentioned in Dispatches for their actions at Kapyong. Mills, the commander of the unit that had called in the mortars and artillery on its own position, would be awarded the Military Cross for his actions.

A war, indeed.

Despite the belated shift at home four decades later, the recognition afforded Korean War veterans by Canadians pales in comparison to the gratitude and gestures the people and government of South Korea have afforded them. The Koreans have awarded them medals, hosted pilgrimages and thrown annual parties in their honour.

South Korean representatives are unfailing in placing wreaths at the National War Memorial in Ottawa to mark Remembrance Day and anniversaries associated with the war and armistice. Visiting South Korean presidents take the time to pay their respects by placing wreaths no matter the season. President Yoon Suk Yeol did so in September 2022.

Some 2.5 million Koreans died, were wounded or disappeared during the three-year war, while 10 million families—a third of the population—were separated. Industry and infrastructure were gutted on both sides.

By war’s end, Seoul had been taken and retaken four times. The sprawling city was left a ruin.

South Korea had lost 17,000 businesses, factories and plants, 4,000 schools and 600,000 homes. The gross national product had declined 14 per cent and total property damage was estimated at US$2 billion.

Its air force virtually erased, the North bore the brunt of the fighting after September 1950. The U.S. Air Force dropped more than 350,000 tonnes of conventional bombs and almost 30,000 tonnes of napalm on North Korean cities, and fired 313,600 rockets and 167 million machine-gun rounds.

The North Korean leader, Kim Il Sung, said the country’s economy had been destroyed. It had lost 8,700 industrial plants, 367,000 hectares of farmland, 600,000 houses, 5,000 schools, 1,000 hospitals and 260 theatres.

Historian James Hoare reported that the North’s national income in 1953 was 69.4 per cent that of 1950; electricity production was reduced to 17.2 per cent of 1949 levels, while coal was down to 17.7.

“There had been a huge loss of able-bodied men either killed or who fled South,” wrote Hoare.

“Effectively, therefore, apart from the end of the fighting, both sides found themselves in the summer of 1953 with nothing to mark and nothing to celebrate.”

Some “conflict.”

Yet, for South Korea at least, the end of the war would mark the gradual beginning of a new age. The country would rebuild and far surpass anything it had known or could have expected before in terms of development and prosperity. It’s now a cultural phenom, a tech giant, and Seoul a sparkling jewel of southeast Asia.

“The country went from a war-torn, impoverished nation to a global industrial powerhouse in just two generations,” wrote Chung Min Lee in a November 2022 essay for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

“Before this turn of events, no one could have imagined that South Korean actors would win an Oscar and an Emmy or that K-pop would reach a global audience.

“A country that relied on U.S. aid until the 1960s is now investing tens of billions of dollars to build new electric vehicles, next-generation batteries, and semiconductors in the United States.”

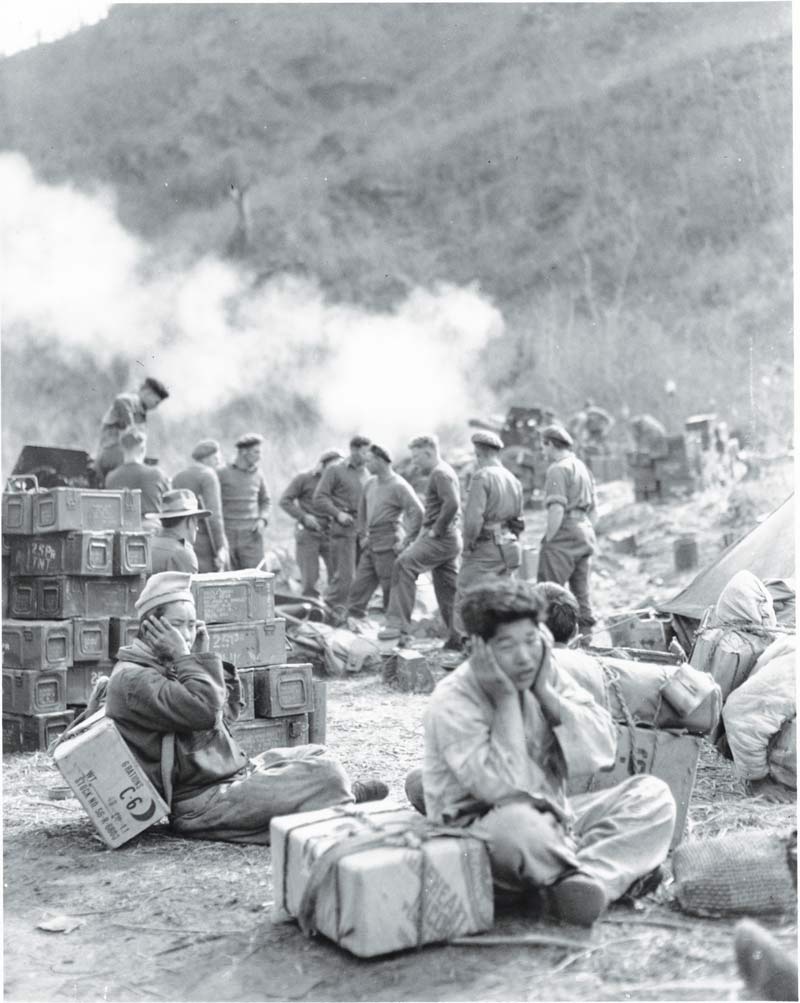

Korean ration-bearers pause near an active Royal New Zealand Artillery battery en route to 2 PPCLI positions. [Bill Olson/LAC/SF-1314]

While South Korea has its problems, too, it’s in its triumphs that the veterans of the Korean War take pride. They may not have left behind a united Korea, but their war preserved the South’s freedom and, ultimately, its means to prosper.

In a Dec. 1, 1953, telegram to the U.S. State Department, Arthur H. Dean, special U.S. envoy to the post-armistice political conference, effectively laid blame for the impending failure to reach a peace at the feet of South Korea’s president at the time, Syngman Rhee, who had refused to sign the hard-earned armistice and wanted to continue fighting.

“Rhee is presently very querulous,” wrote Dean. “Thinks he was tricked into armistice. Now thinks defense pact and economic program are dishonorable bribes to him not to unify Korea by force.

“He sees his lifetime dream of a unified Korea rapidly fading.”

Dean said he had the “distinct impression Rhee now feels the free world does not deserve a fighting Korea, that the rest of us have lost our courage to fight Communism and he would be glad to see us go.

“He recites in detail every bit of concession we made to get an armistice and in working out a demilitarized zone and he is convinced, if we do not fight, [a peace conference] will merely result in yielding up one concession after another by our side to a final surrender of all Korea. Any constructive suggestions by us are, of course, outright concessions to Communists in [South Korean] view.”

And, so, the North of Kim Jong Un today remains a hostile neighbour—a hoarder of nuclear weapons, a source of regional instability, and a continuing threat to world peace.

It has conducted multiple missile tests and at least six times announced it will no longer abide by the armistice. It has violated its terms dozens of times, including via military attacks. Both sides conduct provocative military exercises.

In December 2022, five North Korean drones crossed the demilitarized zone into South Korea. South Korea scrambled helicopters and fighters to intercept them. A South Korean helicopter fired on one of the drones, but none are known to have been taken down. A UN investigation concluded both sides violated the armistice.

Some have advocated an armistice as the most efficient means to end the current fighting in Ukraine. But in a December 2022 essay, the Seoul-based American analysis site NK News said the example set by the Korean armistice doesn’t bode well for success in Eastern Europe.

“The Korean War armistice wasn’t meant to last forever, but an end-of-war declaration, let alone unification, looks less and less likely every year,” wrote analyst James Fretwell.

“And that may be the key lesson to draw from the Korean War precedent: While ending active hostilities, the armistice laid out no clear path for a formal peace or unification. The result has been undying division—whether anyone wants it or not.”

Advertisement