Burnt, broken and in agony, RCAF aircrew received vital support from the Guinea Pig Club

A burn patient reclines in a saline bath, attended by medical staff. [Queen Victoria Hospital/East Grinstead Museum/EGRTM 2773.230/EGRTM 2773.295]

Sergeant Gerry Dufort, a French Canadian serving with the Royal Air Force, was on a training flight near Durham, England, on Oct. 16, 1941, when an engine failed just after takeoff. The Whitley Mk V bomber with a full load of fuel crashed and burst into flames.

After smashing out a window in the cockpit, the pilot, co-pilot and Dufort escaped, but all were severely burned. Dufort lost his eyelids and lips and his hands were scorched. He was 21 years old and could be forgiven for thinking he had no future.

But he was about to meet two groups of people who would give him back a zest for living: surgeons who used revolutionary techniques to give him new facial features and fellow airmen who gave him the confidence to show them to the world. He was about to become a member of the Guinea Pig Club.

A flying guinea pig was the emblem of the club nobody ever wanted to join. [Queen Victoria Hospital/East Grinstead Museum/EGRTM 2773.230/EGRTM 2773.295]

Anticipating that an air war would produce many burn casualties, Britain enlisted New Zealand-trained plastic surgeon Archibald McIndoe to head up a new burns centre at the Queen Victoria Hospital in East Grinstead, a village about 50 kilometres south of London. Dufort was among McIndoe’s first Canadian patients.

Although he never joined the military, McIndoe was a warrior who went to battle for his military patients from the beginning. Patients affectionately called him the Maestro; he was as adept at handling bureaucrats as scalpels.

Plastic surgery was so new that there were only three other specialists in England at the war’s outset and great misunderstanding in political, military and medical circles of what was involved in giving back a face or use of the hands to horrifically disfigured servicemen.

McIndoe battled with the British Air Ministry, which had a rule that fliers would be discharged if they couldn’t return to duty within 90 days of injury. He estimated patients with severe burns needed between 10 and 50 surgeries, requiring up to three years of treatment.

While a government minister opposed to extending medical leave toured the hospital, a curtain was left open, exposing one of the ward’s worst cases, soaking in a saline bath.

A burn victim sits in a saline bath in this painting by Alfred Reginald Thomson. [IWM/ART LD 3629/Wikimedia]

“Whether this was shrewd manipulation or fortunate accident is unknown,” wrote Camille J. Walton in The Guinea Pig Club: Social Support and Developments in Medical Practice. The minister changed his mind and went on to fight in Britain’s parliament to extend paid convalescence for RAF crew to two and a half years.

McIndoe won the battle with the military over patients’ rights to continue wearing their uniforms by threatening to go to the media. And he won the medical battle to abandon outdated medical practices.

He revolutionized hospital regimen, breaking the trail of infection by concentrating burn patients in one ward, Ward III, and replacing blankets with layers of linen that could be frequently laundered. And he believed psychological health was necessary to physical healing.

McIndoe, he said, “gave me back my hands.”

“My whole crew was taken to his hospital,” said Dufort in a newspaper interview when he was 93 years old. “He just changed the whole world for us. He gave us a new outlook on life.”

Among other revolutionary changes, patients were encouraged to watch operations and ask questions, familiarizing themselves with procedures they were soon to undergo themselves.

“He made everything possible for me,” said Dufort, who went on to a long career and two marriages. “I had nine operations…and two years in hospital,” during which surgeons fashioned his new eyelids and lips. McIndoe, he said, “gave me back my hands.”

Surgery successful, Gerry Dufort enjoys a cigar. [Queen Victoria Hospital/East Grinstead Museum EGRTM 2751.6]

But equally important was social support. Rank was abolished in Ward III; officers could be seen not only recuperating with other ranks but socializing and becoming friends, often over a beer.

Three months before Dufort came to East Grinstead, a group of patients decided to form a drinking club, with a secondary aim of supporting one another. The initial name reflected their status as patients in the maxillofacial surgery unit: a stray comment about serving as guinea pigs for experimental surgical techniques sparked the Maxillonian Club, whose members called themselves Guinea Pigs.

Within a year, they dropped the first part of the moniker and became simply the Guinea Pig Club, which grew to more than 640 members, including 176 Canadians, one of whom, in club parlance, earned a Bar to his membership card, reported Emily Mayhew in Guinea Pig Club.

Gordon (Freddie) Frederick served on the first club committee while recovering from burns suffered during service with a fighter squadron in 1941. He returned to recover from facial and leg injuries suffered on D-Day, aboard a Mosquito observer that plunged into the English Channel.

“I…was under long enough to get several good swallows of the stuff that England rules, and generally wish I had been a better boy and kinder to my mother,” said Frederick, in a wry remark typical of Guinea Pigs.

Members’ black humour was evident from the start, when they chose as treasurer a member deprived of the use of his legs, so he couldn’t run off with the funds, and a secretary without use of his hands, so they wouldn’t be bothered by lengthy minutes. They called their ward the sty. The sandman (anesthetist) put them to sleep when they were on the slab (operating table) awaiting the chop (surgery).

The club could not have better suited McIndoe’s aims for keeping up morale between operations, when patients “have a strong tendency to drift and do nothing, to wallow in self-pity and become thoroughly introverted,” he said in a postwar lecture. He was elected club president.

Between operations, willing and able patients were loaned out for jobs to keep them active and focused on something other than their injuries and to make them feel they were contributing to society, observed Rita Donovan, who interviewed dozens of veterans for her book, As for the Canadians: The Remarkable Story of the RCAF’s “Guinea Pigs” of World War II.

“It is one thing to cure the patient of his disfigurement and deformity, it is another to…end up with a normal human being,” said McIndoe. Trust and confidence were required for recovery and that depended on close relationships between doctor and patient—and with each other.

“We are the trustees of each other,” said McIndoe. “We do well to remember that the privilege of dying for one’s country is not equal to the privilege of living for it.”

Those beliefs were thoroughly endorsed by Ross Tilley, one of only five plastic surgeons in Canada and recruited by McIndoe to join the team at East Grinstead.

Surgeon Ross Tilley receives an air raid siren as a retirement gift. [Queen Victoria Hospital/East Grinstead Museum/EGRTM 2773.230/EGRTM 2773.295]

The Royal Canadian Air Force operated 47 squadrons overseas, flying reconnaissance, bombing and fighter operations. As well, thousands of Canadians served in the RAF. Aircrew were often intermingled, so it made sense for all air casualties to be treated in the British system. Canadians were the largest minority, so it was also sensible for the burn unit at East Grinstead to have staff from Canada.

Wing Commander Tilley was appointed RCAF principal medical officer overseas in 1941 and was recruited by McIndoe in early 1942. Ward III patients were immediately enamoured of the cheerful Canadian, whom they dubbed Wingco.

Tilley and McIndoe extended their care beyond the walls of the hospital into the community, where they persuaded local citizens to become part of the airmen’s rehabilitation—to welcome them into their homes, shops, restaurants, pubs and theatres. They also schooled residents not to react to patients’ appearance.

The staff at the Whitehall restaurant decided to “look them full in the eyes and just see them…not look away from them, and speak to them,” recalled waitress Mabel Osbourne. “We got so used to it we never took any notice after that.”

Patients were stopped in the street to chat, residents invited them home to tea, and local girls asked them out to dances and concerts. The children had even been taught not to stare, according to an article in Reader’s Digest.

Publican Bill Gardner became much loved in the piggery and was frequently mentioned in The Guinea Pig magazine. “He contributed very largely to our happiness,” recalled British veteran William Simpson in his memoir The Way of Recovery. “Whenever we felt particularly conscious of being ugly and deformed, we always knew there was a welcome waiting for us at Bill’s.”

“East Grinstead was absolutely marvellous to us,” said Dufort. “We just did not feel as if we were different to anyone else—and never have since.”

After permanent assignment to the hospital, Tilley assembled an all-Canadian plastic surgery operating team that, from July 1942 on, handled as many Canadian cases as they could.

“We tried to help create a Canadian atmosphere,” said nurse Frances Oakes. Staff made an extra effort for the young men, such as sewing donated zippers into patients’ clothing so they could dress themselves when unable to handle buttons.

Orderly Johnny Ingram “treated me with respect and uncommon devotion,” recalled Leo Tremblay in Mayhew’s book. “[He] would take me out in a wheelchair into East Grinstead to the Whitehall Restaurant. We would have a few—sometimes more than a few—beers and excellent food.”

The Canadian medical team soon became familiar with treating flesh seared by hot surfaces as flyers escaped from infernos, as well as airman’s burn, a pattern of destroyed flesh peculiar to crew who sat directly above or behind aircraft fuel tanks.

Few survived fuel tank explosions. McIndoe estimated about 22,000 air crew burned to death during the war. Of the 4,500 recovered alive from crashes, 60 to 80 per cent suffered burns to the face and hands.

The burns were deep third-degree burns, “as if the patient had been thrust into a furnace for a few seconds and withdrawn,” said McIndoe. The eyelids and hands particularly suffered.

“I watched him rebuild faces, noses, ears and fingers of severely burned airmen.”

In the crash of a Wellington bomber in January 1943, Jack Reynolds of Saskatchewan felt that blowtorch effect, suffering third-degree burns on his face, arm and leg. He spent the better part of a year at East Grinstead while his burns healed and his eyelids and eyebrow were repaired.

“My being somewhat scarred has never at any time been of concern, and I have to thank Dr. Tilley,” said Reynolds, one of several airmen quoted here from Donovan’s book.

“I watched him rebuild faces, noses, ears and fingers of severely burned airmen…[but] much greater than the plastic surgery he performed was the confidence he instilled in each of us,” said Reynolds, who was back flying in December 1944.

There was no lack of compassion. When patient Owen Jones got the news that his brother had been killed, Tilley invited him to the local pub where he “spent hours with me and talked me through my grief.”

As the number of Canadian cases grew and Ward III became overcrowded, Tilley persuaded the Canadian government to build a 50-bed Canadian wing onto the hospital, which opened in July 1944. From kitchen to ward to operating room, it was staffed completely by Canadians.

This achievement is noted in lyrics to the Guinea Pig Club anthem:

We’ve had some mad Australians,

Some French, some Czechs, some Poles.

We’ve even had some Yankees,

God bless their precious souls.

While as for the Canadians—

Ah! That’s a different thing.

They couldn’t stand our accent

And built a separate wing.

“There were three types of Guinea Pigs,” said Lionel (Hank) Hastings in a Regina Leader-Post interview. “There were fried, mashed and hash-browned. I was primarily mashed.”

They revolutionized burn care, treatment and rehabilitation.

Hastings, an RCAF navigator, had 50 bombing missions under his belt by October 1944. He was on a non-combat flight when the aircraft’s engines failed over Belgium. As the pilot started to glide the plane to a nearby airport, Hastings went to secure passengers. Before he could get back to his seat, the plane hit some telephone wires and crashed.

Hasting’s face was fractured in 32 places, his spine in three. He spent months in a body cast as his broken body healed. Tilley “made you realize that it was great to be alive and you were indeed one of the most fortunate people in the world to have that privilege.” After the war, Hastings became a dentist, married and had a family.

McIndoe and Tilley had created the perfect atmosphere to advance the science behind burn treatment. The ready supply of patients allowed their medical teams to quickly identify outdated treatments that needed to be abandoned, old techniques that could be perfected and new techniques to be developed. They revolutionized burn care, treatment and rehabilitation.

In the First World War, aircrew with severe burns did not survive long. Without the barrier provided by skin, fluids seeped and evaporated from burned tissue and lethal bacteria attacked. Patients went into shock and died.

During that war it was discovered that replacing fluids reduced mortality rates, and this new science was developed further after the war. Antibiotics also began to lower death rates in the 1930s.

But patients who recovered from severe burns were often left with scars so horrific they were reluctant to go out in public. McIndoe and Tilley played a large part in changing that.

At the beginning of the Second World War, coagulation treatment was standard practice. A substance that formed a hard, protective shell was painted over the burn; gentian violet for the face, tannic acid for hands.

But tannic acid proved less than successful on serious burns. The hard shell restricted circulation, which was further constricted by swelling. The result was infection that was hidden and discovered only after it began oozing or stinking. Too many fingers and hands subsequently had to be amputated.

Following a crash in Malta in 1941, air gunner Bill Martin was pulled from the fiery wreckage with broken bones and airman’s burns. Tannic acid was applied to his hand in hospital but an infection developed, noticed only when it began oozing from beneath the hard shell, which was removed in a procedure so painful it had to be done while he was under general anesthetic. Luckily, he kept his hand and fingers.

Bill Martin served as chief of the Canadian wing of the club. [Queen Victoria Hospital/East Grinstead Museum]

Those who didn’t lose digits were still often left with useless hands. RAF fighter pilot Geoffrey Page watched his hands deteriorate after the tannic acid covering was removed.

“Fraction by fraction the tendons contracted, bending the fingers downwards until finally the tips were in contact with the palms,” Page wrote in Shot Down in Flames. “The delicate skin toughened by degrees until it had the texture of rhinoceros hide, at the same time webbing my fingers together until they were undistinguishable as separate units.”

“Results of coagulants applied to burns of the face were equally distressing,” wrote Kevin Mowbrey in an article on Tilley in the Canadian Journal of Plastic Surgery in 2013. Gentian violet left skin leathery and so taut that eyelids were unable to blink, resulting in ulcers and scratches to the cornea, too often followed by blindness.

Royal Air Force pilot Geoffrey Page, with his fiancée Pauline Bruce, was a founding member of the Guinea Pig Club. [Queen Victoria Hospital/East Grinstead Museum]

McIndoe successfully campaigned to have the British Ministry of Defence ban the use of tannic acid. In its place, an antiseptic cream was distributed to Allied military medical departments.

The badly burned were in for a long haul.

Doctors at East Grinstead followed a more intensive treatment regime that did not result in such thick scar tissue. Wounds were kept open and regularly soaked or bathed in a saline solution. Dressings soaked in an antiseptic jelly were frequently and easily changed, often falling off in the saline bath.

Patients would soak in the bath for an hour up to three times a day. The regime was particularly important for maintaining flexibility of hands; improved blood flow allowed for the salvage of more fingers.

The badly burned were in for a long haul. “Any failed graft in a facial repair is a major disaster to the patient, whose confidence and trust is maintained by a steady succession of successful operations,” said McIndoe. Up to eight surgeries per patient were planned each year, with patients spending a month or so in hospital, followed by a few weeks’ break, then back for more reconstruction and skin grafts.

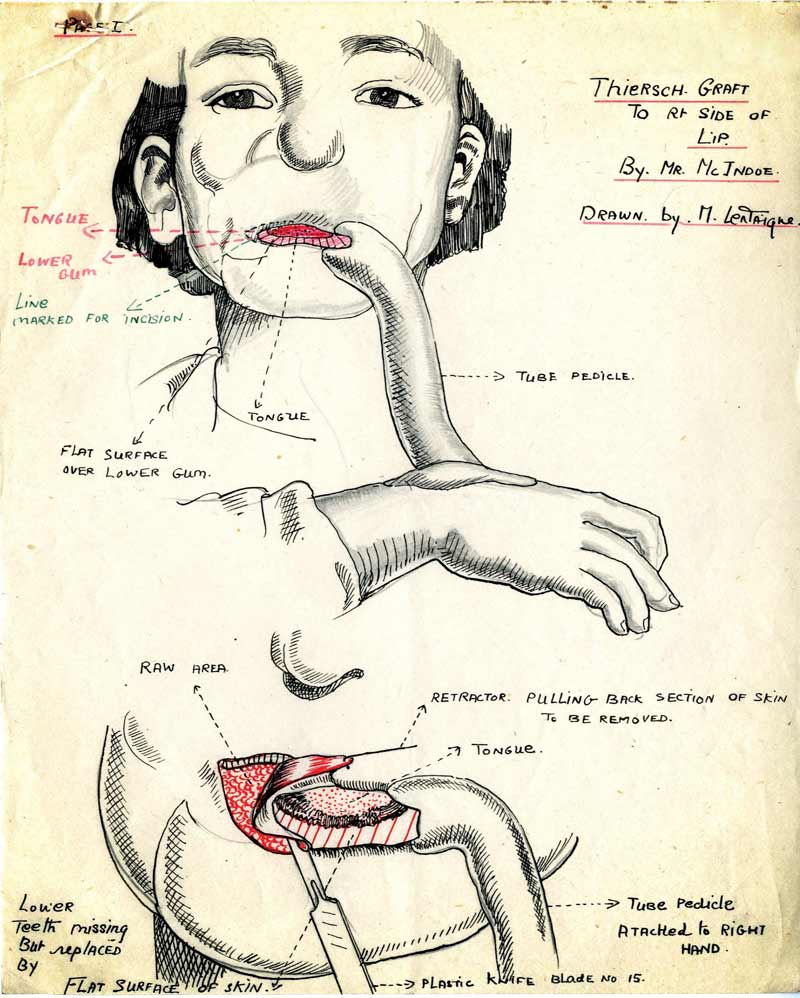

Many grafting techniques were used at East Grinstead, depending on the severity of the burn. The most spectacular were pedicle grafts for large burns. Skin grafting involves harvesting healthy skin from one area of the body to replace burned skin. But to grow, it needs a blood supply or it will die. Tilley and McIndoe used pedicle grafts, pioneered in the First World War, to “waltz” skin from one area to another.

A pedicle is a flap of skin harvested from underlying tissue, remaining attached along one edge. The sides are sewn together, forming a tube. The unsealed end is sewn onto another area, where it establishes a blood supply. It can then be severed and used as a graft or somersaulted to a new position. Moving skin from neck to nose, or from belly to arm to face was not only a slow process, but required patients to stay still in awkward and painful positions.

Martin became very familiar with grafting techniques at East Grinstead. As the war permitted, he hopped from hospital to hospital from Malta back to Britain, arriving in April 1942, thoroughly disenchanted with doctors.

He came under Tilley’s care for eight months, over which time he had seven operations to remove scar tissue, fix his nose, replace his lips, and repair damage from earlier surgical repairs and failures.

First came radiation to soften scar tissue, then “a complete graft of the back of my hand and the webbing between the fingers, completed in one operation.” Then more grafts. “Part of my nose came from my thigh, part of my cheek came from my stomach, part of my upper lip came from under my arm.”

“So successful was the work of the staff from both a surgical and psychological point of view that approximately 80 per cent of the aircrew patients recovered sufficiently to return to flying duties,” reported the Official History of the Canadian Medical Services.

After the war, Tilley and Martin returned to Canada. Tilley was instrumental in establishing the profession of plastic surgery, and Martin returned to live a full life, marrying and raising a family. Both were involved in the Canadian arm of the Guinea Pig Club.

The club limped along in Canada after the war, coming truly alive after a reunion in East Grinstead to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the parent club. A 1972 reunion was planned in Canada and the Canadian wing of the Guinea Pig Club was founded. Tilley served as club president and continued to operate on its members for four decades after the war.

Few members are left now, and the club that provided them with support and solace for most of their lives will soon disappear on both sides of the Atlantic as the last of them is claimed by age.

Advertisement