The Mary Rose as painted by British maritime artist Geoff Hunt. [Geoff Hunt/Mary Rose Trust]

In 2021, scientists published the results of isotope analysis of the teeth in eight of 179 crew whose remarkably well-preserved remains were recovered along with 19,000 artifacts and much of the ship, which was sunk on July 19, 1545, during the Battle of the Solent off England’s south coast.

Isotopes helped construct what one expert described as “unparalleled” biographies suggesting several of the tested subjects were raised on African, Mediterranean or other diets differing from the relatively limited fare on which most Britons relied at the time—namely bread, soups, stews, ale and meats.

At least three of the eight could have come from southern European coasts, Iberia or North Africa and, while the others originated from diverse regions of Britain itself, it is believed some of their recent family histories reached far beyond the home islands.

“Our findings point to the important contributions that individuals of diverse backgrounds and origins made to the English navy during this period,” said lead author Jessica Scorrer of Cardiff University.

“This adds to the ever-growing body of evidence for diversity in geographic origins, ancestry and lived experiences in Tudor England.”

Based on context and associated artifacts, the Mary Rose Trust even attributed professions to seven of the sampled individuals, dubbing them cook, archer, royal archer, gentleman, carpenter, officer and purser.

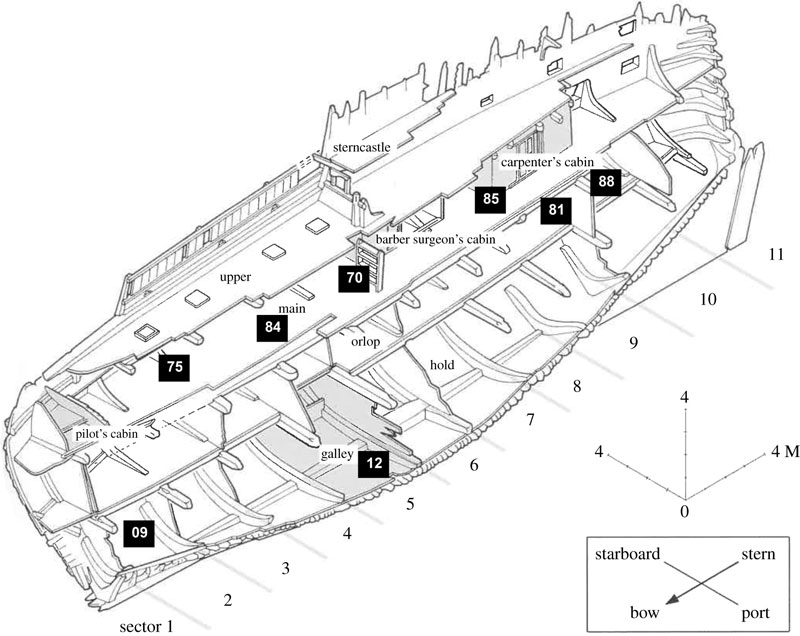

A diagram of the Mary Rose indicating the locations of individuals sampled for this study. [Mary Rose Trust]

“This finding adds to the growing evidence for Black Africans in professional roles among the Tudor population,” said the study. “Most records referring to African residents are from parishes near port towns, such as London, Southampton, Bristol and Plymouth, which may have attracted people outside of Britain for trade.”

The young mariner “may well have been raised in or near a port town in the southwest of England and represents the first direct evidence for mariners of African descent in the navy of Henry VIII.”

Comparing their findings with known samples in a forensic databank, the researchers’ work was made easier and more precise by several circumstances, including the fact that the exact date and circumstances of death were known and the wreck was encased in preserving estuarine silts soon after it went to the bottom.

The hull and its contents, including more than 40 per cent of the ship’s complement, were recovered in 1982 and subsequently conserved and displayed at Portsmouth Historic Dockyard.

Crews were made up of skilled mariners, soldiers and gunners, along with a broad range of trades.

Prior historical and scientific evidence has pointed to diverse naval recruits within the English fleet, but the direct scientific evidence acquired from human remains from the Tudor period is limited.

Commissioned by Henry VIII, the flagship Mary Rose was in Tudor naval service for all but four years of his 1509-1547 reign.

English naval ranks in 1545 numbered 8,000. Crews were made up of skilled mariners, soldiers and gunners, along with a broad range of trades and professions, including cooks, carpenters and pursers, who handled finances aboard ships.

During wartime, the English also hired retinues, or private armies, from English lords along with foreign mercenaries from Germany, Netherlands, Italy and Spain. Sixteenth-century writings and other evidence indicate Africans were among crews aboard English merchant and pirate vessels.

It’s not the first time isotope analysis has been conducted on Mary Rose’s crew. Research on the ship and its inhabitants has been ongoing since they were raised from their silty grave.

A 2009 isotope analysis of 18 of the recovered remains found that at least a third, and up to almost two-thirds, originated from warmer or more southern locales than the British Isles. It also claimed that communication issues among the multinational sailors contributed to the ship’s fate. The study’s findings have been disputed.Bone and cranial analysis, as well as associated artifacts, suggests diversity among the crew.

Another study said Mary Rose was manned by a “semi-permanent, professional crew.” Many of the remains it sampled were of young men with “age-related vertebral pathologies potentially caused by continuous work aboard a warship.”

The scientists believe one of the archers came from a port in southwest England, such as Plymouth in Devon or Fowey in Cornwall. The cook is thought to have come from a West Country coastal area. The officer could have been raised in the Midlands or Wiltshire, while the purser is thought to have been raised on the banks of the Thames Estuary.

Other evidence, including bone and cranial analysis, as well as associated artifacts, suggests diversity among the crew.

“There are indications of foreign connections among the Mary Rose crew in the form of various ceramic types, including English, French, Low Countries, Rhenish and Iberian wares,” said the latest study, conducted by eight British experts and published in the Royal Society Open Science journal. The Royal Society, founded 360 years ago, is the world’s oldest national scientific academy.“These may represent personal belongings brought on board by recruits from overseas, although similar wares would have been available at English ports due to trade connections. In addition, whetstones belonging to the barber surgeon and carpenters have been analysed and may have originated from Brittany, the Channel Islands, Scottish Highlands or regions in southern Europe and North Africa.”

The gentleman’s remains were found close to a chest containing a carved bone panel similar to those produced in northern Italy in the 14th and 15th centuries.

While the items could have been acquired through trade and don’t necessarily represent Italian origins, the study said: “A coastal region in southern Europe is a likely place of origin for this individual based on his isotope values and the historical/artefactual evidence.”

Spanish coins and Spanish-style tools found in the carpenters’ cabin indicate at least one of the six carpenters aboard ship could have come from the Iberian Peninsula. Analysis of remains of the man found in proximity to the cabin suggest he came from inland southwest Spain.

“Four adzes with a ‘stirrup’ design commonly found in Spain during this period were recovered, and there were a few coins identified as Spanish in an embroidered leather pouch found in a personal chest in the cabin. Combining isotope and artefactual evidence, inland southwest Iberia provides a plausible area of origin.”The second bowman became known as “the royal archer” because he had a leather wrist guard bearing the symbol of a pomegranate, associated with Catherine of Aragon, Henry VIII’s first wife. The Moors brought the fruit to Europe from Africa in the medieval and early-modern periods.

“We never expected this diversity to be so rich.”

His isotope analysis suggests the man could have been raised in northeastern Morocco, the Atlas Mountains in Algeria, the Chotts—or salt lakes—in southern Tunisia or possibly Spain.

The Mary Rose Trust was a primary sponsor of the project. Alexzandra Hildred, its head of research and curator of ordnance and human remains, said the “variety and number of personal artifacts recovered which were clearly not of English manufacture made us wonder whether some of the crew were foreign by birth.”

“We never expected this diversity to be so rich,” she said. “This study transforms our perceived ideas regarding the composition of the nascent English navy.”

The Battle of the Solent pitted the fleet of Francis I of France against that of Henry VIII. It ended without a clear victor, though the four-masted carrack, believed to have been named for Henry’s sister Mary and the Tudor emblem—a rose—sank after a volley of French gunfire on the battle’s second and final day.

Interestingly, period papers from the High Court of Admiralty showed that one of the first bids to salvage the wreck of Henry’s favourite ship was attempted soon after it sank by a West African diver, Jacques Francis.

Advertisement