The unveiling of the Canadian National Vimy Memorial in France on July 26, 1936, was witnessed by 3,000 veterans of the battle

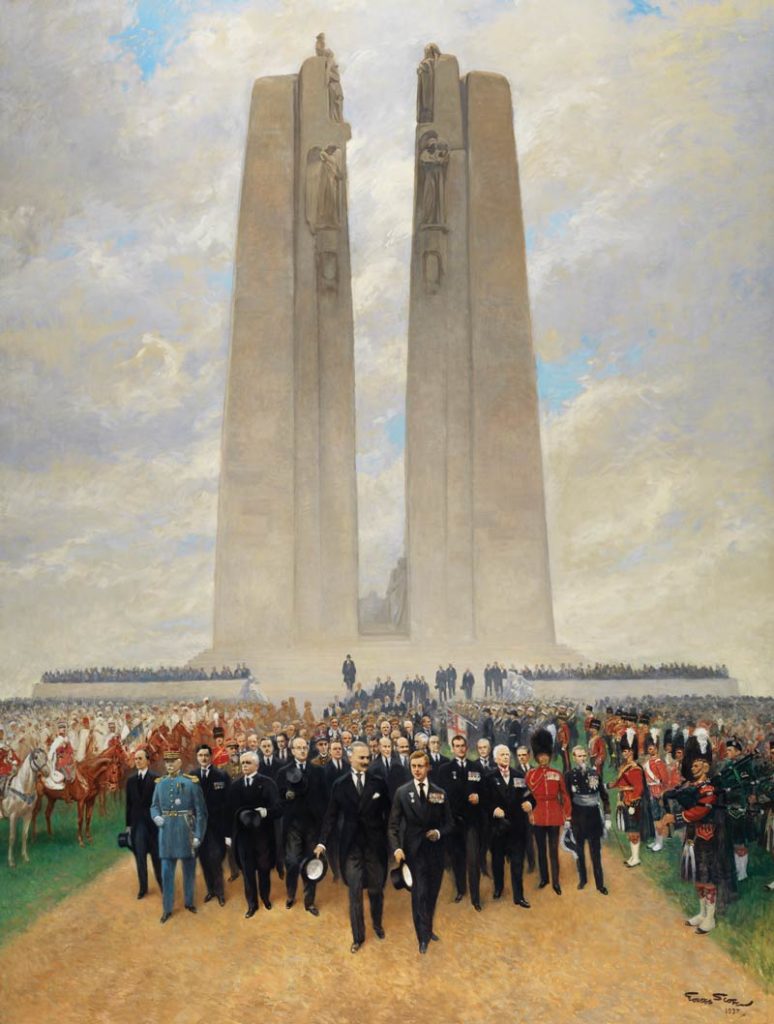

Wearing a commemorative Canadian Legion medal on his right lapel, King Edward VIII leads Vimy Pilgrimage participants during the unveiling of the Canadian National Vimy Memorial in France. [Georges Bertin Scott/CWM/19670070-014]

On July 26, 1936, 11 years and $1.5 million after construction began, 100,000 people gathered on the slopes of Vimy Ridge in France for the unveiling of one of the most striking war memorials in all of Europe.

The Canadian National Vimy Memorial, designed by Toronto’s Walter Allward, stands at the crest of the ridge where some say the nation was born—an imposing memorial to more than 11,285 Canadians who died with no known grave in France during the Great War.

A monument to peace, it is the centrepiece of a 91-hectare battlefield park at the site where all four divisions of the Canadian Expeditionary Force fought together for the first time—and won where others could not.

Some 3,000 veterans of the battle walked the land over which they had fought and 3,598 of their brethren had died. This time, many had their families at their sides.

“This glorious monument crowning the hill of Vimy is now and for all time a part of Canada, though the mortal remains of Canada’s sons lie far from home,” declared King Edward VIII at the unveiling. “Their immortal memory is hallowed upon soil that is as surely Canada’s as any acre within her nine provinces.”

Carving the stone sarcophagus for the memorial in 1935. Designer Walter Allward chose limestone from an ancient Roman quarry in Seget, Croatia. [LAC/3612539]

The Vimy Pilgrimage constituted the largest single peacetime movement of people from Canada to Europe to that time. Ottawa waived passport fees and even issued special Vimy Pilgrimage passports. The government and private sector also provided paid leave for participating employees.

The Canadian Legion co-ordinated accommodations and transportation. Five transatlantic liners, escorted by two Canadian warships, departed Montreal on July 16 and arrived in Le Havre on the 24th and 25th. The pilgrims were lodged in nine cities throughout northern France and Belgium and commuted in 235 buses. The three-and-a-half week trip cost $160 per person (equivalent to $3,000 today).

At the memorial, Edward mingled. Military aircraft flew low overhead, dipping their wings in salute. At home, listening over radios in kitchens and sitting rooms, at Legion halls and lunch counters, the country was transfixed.

Three years later, Canada was fighting another war in Europe and around the globe.

The columns of the Vimy Memorial tower over sailors marching in review shortly after the unveiling. [Toronto Star Photo Archive/Baldwin Collection/Toronto Public Library]

Edward greets Charlotte Wood of Winnipeg, Canada’s first National Memorial (Silver) Cross Mother, who lost two sons in the war. French President Albert Lebrun looks on. [Smith Archive/Alamy/2BW3J04]

Canada Bereft, the centrepiece of the massive monument, was carved from a 30-tonne block of stone. [Canadian Government Motion Picture Bureau/LAC/3224327

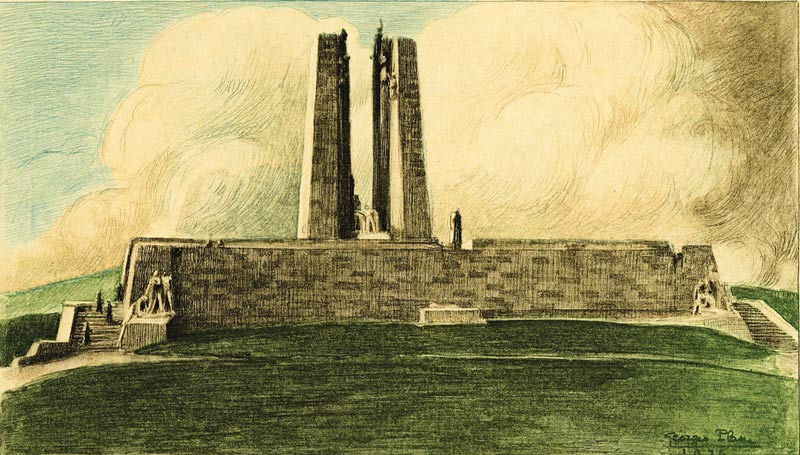

French artist Georges Plasse made drawings of Allward’s vision. [Georges Plasse/Walter Seymour Allward/Toronto Reference Library]

Spirits of soldiers ascend the slope in Australian Captain William Longstaff’s painting “The Ghosts of Vimy Ridge.” Allward said he had been inspired by a wartime dream in which dead soldiers “rose in masses, filed silently by and entered the fight to aid the living.” [CWM/19890275-051]

The memorial is inscribed with the names of 11,285 Canadians who died with no known grave in France during the Great War. It remains a point of pilgrimage to this day. [Nigel Jarvis/iStock/1277880634]

Advertisement