Canadian troops return triumphant from the Vimy front, their celebrations tempered by the loss of 3,598 comrades killed and 7,004 wounded.[William Ivor Castle/LAC/3194757/Colourization The Vimy Foundation; ]

Planned and executed with precision, the attack on Vimy Ridge redefined the Canadian Corps as an elite formation.

The victory at Vimy Ridge in April 1917 is the one military story that most Canadians know. Some of our best writers—journalists and historians alike, from Pierre Berton to Tim Cook—have written books on Vimy and the event has been celebrated in textbooks, in the federal government’s material for new citizens, on our money and in the stunning Canadian National Vimy Memorial in France.

Celebrations on the 90th and 100th anniversaries attracted thousands of high school students who raised money to travel to Vimy, and the CBC devoted hours to broadcasting the event to those at home. After more than a century, Vimy remains firmly set in the Canadian consciousness.

The war was not going well for the Allies in the spring of 1917. The Russians were tottering and the Americans, who had recently joined the war, would take months to train and equip troops and get them to the front. The endless toll of dead and wounded at Verdun and the Somme and the mounting financial costs of total war had left Britain and France—and Canada too—near the breaking point.

The enemy was also suffering because of food and materiel shortages caused by the British naval blockade, and German casualties were enormous. But if the war had ended on April 1, 1917, the Germans—occupying most of Belgium, large parts of northern France and huge swathes of Russian territory—would certainly have been deemed the victor.

Lieutenant-General Julian Byng, inspects one of the German guns captured during the battle.[LAC PA-001308]

Field Marshal Douglas Haig, commanding the British Expeditionary Force that included the four divisions of the Canadian Corps, planned a big push in the Arras sector for April. The Canadians, commanded by British Lieutenant-General Julian Byng, were ordered to take Vimy Ridge, the long and well-fortified feature that protected much of the industrial and mining industries in German-occupied France.

This was a difficult task—earlier Allied assaults on Vimy had failed with heavy losses and the Germans seemed well prepared to hold on no matter what the Allies could do.

But orders were orders, and Byng and his staff began to plan. In January, Byng sent Major-General Arthur Currie, commanding the 1st Canadian Division, as a member of a British delegation that visited the French armies to learn how they had fought at Verdun.

Currie’s report stressed the importance of artillery counter-battery preparation that eliminated the enemy guns, and he noted that the French had perfected the creeping barrage that moved effectively just ahead of the advancing troops. He saw that they had developed platoons capable of independent manoeuvres with distinct sections of machine-gunners, rifle-grenadiers, bombers and riflemen. Unlike the Canadians, the French no longer attacked in waves; instead, platoons could support their own advance with fire and movement and bypass enemy strongpoints.

Currie was also deeply impressed with the rehearsals and reconnaissance that the French conducted prior to an attack, so much so that the soldiers became “as familiar as possible with the ground over which they were to attack.” He pointed out that the French pulled the assault forces out of the line for special training and ensured that the men were “re-equipped, re-clothed, fed particularly well, had entertainments provided for them, and consequently returned to the line absolutely fresh and highly trained.”

Members of the 8th Battalion (90th Winnipeg Rifles) conduct bayonet practice with bags of straw on Salisbury Plain.[ LAC/CWM/19930003-359]

Currie also admired the French practice of distributing maps and photographs widely, not only for senior officers well behind the lines as was the practice in the British Army. Soldiers needed to know where and why they were attacking and what was expected of them. On his return, Currie recommended that the Canadians emulate the French, and Byng listened and acted, changing the training and organization of the infantry platoons, cutting their number of soldiers down to 35 or 40, the most a junior officer could manage to lead.

The attack at Vimy, thanks in part to Currie’s report, was preceded by unheard of training in fire and movement supported by the specialist roles and, as the official history by G.W.L. Nicholson noted, “a full-scale replica of the battle area was laid out…to the rear” where units from platoons to divisions “rehearsed repeatedly,” so often that some soldiers grumbled about “their officers’ silly games.”

Forty thousand maps were distributed, and a new artillery plan was launched: the guns began their battlefield preparation two weeks before the attack, and the heavy artillery concentrated its fire on the enemy batteries. The Germans certainly knew an attack was coming, but they did not know when. Moreover, tactical surprise would be achieved by moving troops into specially created tunnels dug into the chalky ground very close to the front-line trenches and maintaining the tempo of gunfire until just before the assault.

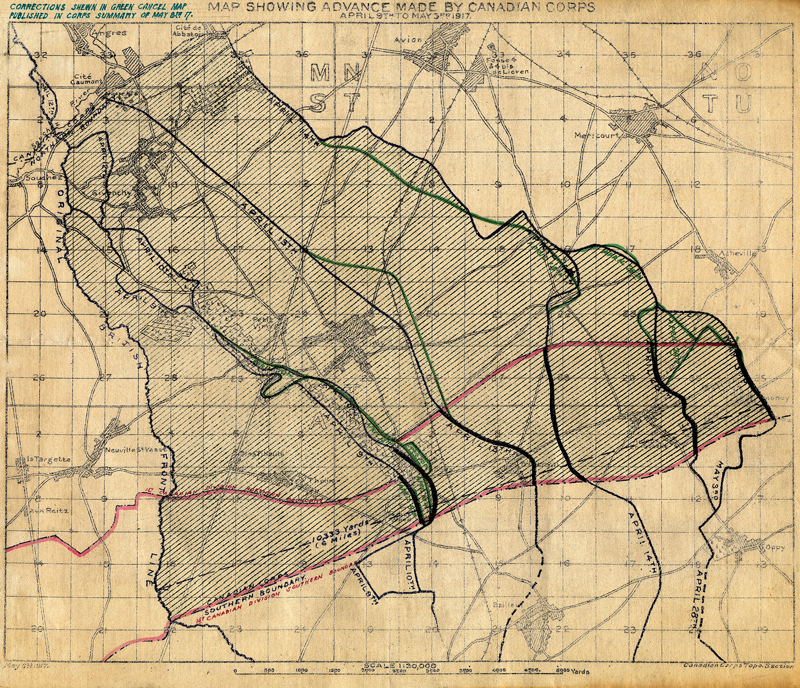

A period map illustrates the boundaries, objectives and strongpoints confronting the Canadians between April 9 and May 3, 1917. [CWM/19750215-030a]

Ammunition for the guns came forward in profusion.

Byng’s plan was ready by March 5. His four divisions, fighting together for the first time, would be positioned in order with the 1st Division on the right and the 4th on the left. There were four objectives, each designated by a coloured line on the map: the entire ridge and the enemy’s second line were to be seized in just under five hours. There were 863 guns in support and the gunners had the new No. 106 fuse that could cut the enemy’s barbed wire. The rolling barrage was to advance in 50-yard steps. Ammunition for the guns came forward in profusion (they would fire more than a million shells between March 20 and the capture of the ridge), much of it hauled by newly laid tramlines. Water for men and horses reached the front through pipelines; signallers buried telephone lines to survive enemy shelling; and the tunnellers carved out large alcoves for battalion and brigade headquarters. Every soldier knew his task.

“I am a rifle grenadier,” Private Ronald MacKinnon of the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry wrote in a letter home. “We have a good bunch of boys to go over with and good artillery support, so we are bound to get our objective alright.” MacKinnon was killed in the battle.

Canadian artillery members fire a captured German 4.2-inch gun at retreating enemy during the battle.[LAC/PA-001083]

The attack began at 5:30 a.m. on Easter Monday, April 9, with snow and sleet blowing in the Germans’ faces. With what Lieutenant Stuart Kirkland described as “the most wonderful artillery barrage ever known in the history of the world,” the enemy guns and trench lines were hit with high explosives and gas, destroying more than 80 per cent of the German guns and keeping the infantry sheltering in their dugouts.

“The guns all opened at the same moment with a roar like a terrible peal of thunder,” wrote Harold McGill, a medical officer of the 31st Battalion (Alberta), “and for miles all along the German trenches there was the most wonderful display of fireworks caused by our bursting shells.”

The 15,000 infantrymen who led the attack moved steadily forward behind the rolling barrage, their handful of supporting tanks unfortunately unable to move forward because of shell holes and sticky mud. The 1st Division reached the German front line, held by Bavarians, and found most of the defenders still in their dugouts. Mop-up troops soon arrived, and Currie’s soldiers reached the Red Line, their second objective, by 7 a.m., although enemy snipers and machine-gunners were beginning to exact their toll.

The 2nd Division moved quickly across its first objective, the Black Line, and encountered heavy fire only at its second objective which it controlled by 8 a.m. By 9:30, the reserve brigades of the two divisions were moving toward the third objective, the Blue Line.

“Our troops advanced as cool and steady as when they had previously practised,” said McGill, but, in fact, it frequently took great courage to take the objectives. Sergeant Ellis Wellwood Sifton of the 18th Battalion (Western Ontario) charged a machine gun that fired on his men, bayoneted its crew, and held off riflemen moving down the trench toward him by using his own rifle as a club. He was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross.

The 3rd Division had a relatively easy time, taking its first two objectives quickly. Billy Bishop, a young pilot in the Royal Flying Corps whose victories were still to come, watched what to him seemed to be men wandering casually across no man’s land. He could see shells falling among them, but the others continued going forward.

The 29th Battalion (Vancouver) advances across no man’s land despite German barbed wire and heavy fire at Vimy. [William Ivor Castle]

The ground had been torn up by two weeks of shelling, and many of the landmarks intended to help situate the attackers had been destroyed. Some units, advancing too quickly, were hit by the Canadian barrage. Many had close calls.

“[We] were able to extricate our men without getting hurt ourselves,” wrote Major Percy Menzies of the 3rd Division’s 4th Battalion, Canadian Mounted Rifles. “All this time we were troubled by our own shells bursting short, but I was never touched.”

The 4th Division faced real difficulty. Its main objective was Hill 145, which had four lines of strong defences and deep dugouts on the reverse slope. The attack by the 11th and 12th brigades, each with an additional battalion, took the first line, but the Germans in the heavily manned second line of trenches forced the troops back with repeated counterattacks.

Hill 145 remained in German hands until the newly arrived 85th Battalion (Nova Scotia Highlanders) took it that night. The next day, the 44th and 50th battalions followed the barrage in a mad charge down the steep eastern slope, and the 4th Division had the Red Line.

Now all that remained was The Pimple, the northern tip of the ridge.

In the early morning of April 12, the 10th Brigade, attacking in the teeth of a gale, surprised the Germans manning the hill. By 6 a.m. after hand-to-hand fighting, the brigade had taken The Pimple.

From the crest, the Canadians could see eastward as far as the suburbs of Lens, a coal mining town, and the Canadian artillery, struggling forward through the heavy mud, took up new positions to the east of Vimy Ridge. The Germans’ supposedly impregnable position had been taken and the Canadian Corps’ success was hailed in Paris, London and at home.

Byng was the first beneficiary of the victory. Promoted to full general, he received command of the British Third Army. His successor, Currie, received a promotion, a knighthood and command of the Canadian Corps in June, a position he would hold until the war’s end.

Vimy was “the greatest thing the Canadians have been in yet—wonderful,”

The battle was a costly but limited success. The ridge had been taken, but the Germans were not routed. There was no breakthrough—no cavalry had been made available to Byng to exploit success.

In five days of fighting, the Canadians suffered 10,602 casualties, including 3,598 killed—enough that Prime Minister Robert Borden, in London at the time, began to realize that conscription would be needed. Many soldiers were proud of the victory.

Vimy was “the greatest thing the Canadians have been in yet—wonderful,” said Captain William Fingold of the YMCA. “Of course, there have been heavy losses, but it was a great victory.”

Others were just happy to have survived: “It was a hell on earth,” wrote one soldier, “and I am very lucky to be here today.”

Did Vimy matter?

Canadian troops hold a memorial service in September 1917 for the men of the 87th Battalion (Canadian Grenadier Guards) who fell at Vimy. Over the course of the war, impromptu cemeteries sprang up all along the Western Front. Reburials and more elaborate memorials would come later. [LAC/3395020]

In Canadian popular history, Vimy is sometimes painted as a war-winning victory. Major-General Arthur Currie’s Canadians had done something that the Allies previously could not: they had scaled the heights of the ridge and defeated the Germans.

But realists know that Julian Byng, a British general, not Currie, commanded the Canadian Corps in April 1917. We know that most of the ridge the Canadians attacked from the west rose gently with the big drop behind the enemy trenches and on the reverse slope. We understand that there was no breakthrough, no cavalry sweeping through the enemy rear, and that the Germans simply retired several kilometres east to their next defence line. We remember too, that the Canadians suffered 10,602 killed and wounded at Vimy, the greatest losses in any single action in our history, and the killing continued for another year and a half. The myths far outpaced the reality.

Major-General Arthur Currie’s [LAC3213526]

But Vimy did matter. The Canadians began the war as amateurs, but at Ypres, Saint-Éloi and the Somme, they had learned how to fight.

After Vimy, the soldiers understood they had done something great and knew that their battalions, brigades and divisions had come to maturity and made the Corps an elite formation. The war would continue, and the confidence and determination earned at Vimy turned the Canadians into some of the best Allied troops of the Great War.

Advertisement