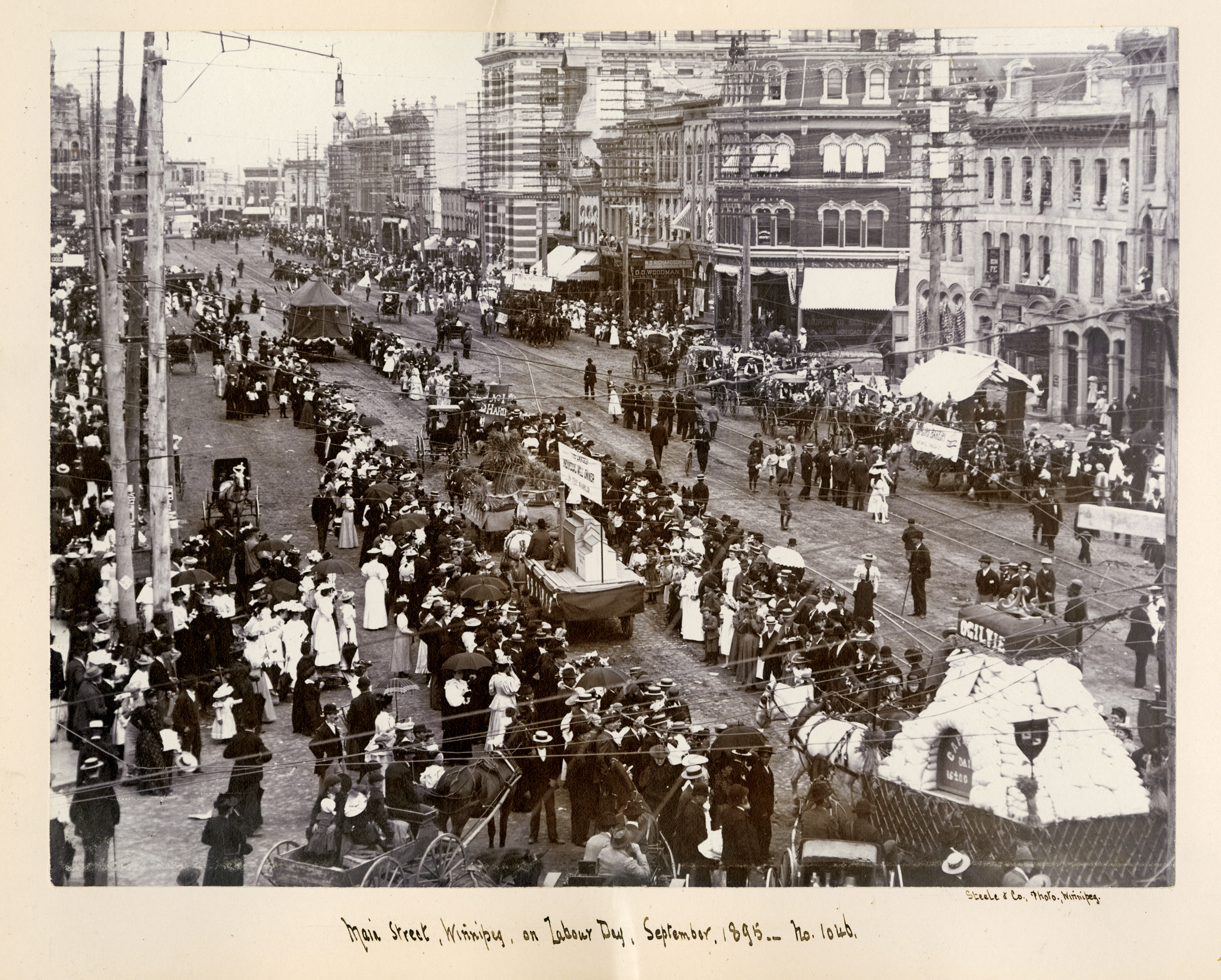

Spectators watch a Labour Day parade on Winnipeg’s Main Street in 1895. [Steele and Co./LAC/R7719-12-2-E]

The 19th century wasn’t a golden era for workers. In Newfoundland, six-year-olds were given the job of splitting fish, while processing was done by 10-year-old girls. Eight-year-old boys worked in Cape Breton coal mines. At Toronto’s Gooderham and Worts distillery, child workers as young as 10 worked long days and were given rations of whisky to help ease the burden.

Things weren’t any better for adults. Twelve-hour days were standard, along with six-day weeks. In company mining towns, most of the workers’ wages went to pay rent for the company-owned houses and to buy supplies at the company-owned store. If the workers threatened to strike, the store would close. Conditions were often unsafe, wages were low and workers could be fired on a whim.

In response to these conditions, the “Nine-Hour Movement” began in Hamilton in 1869 and soon spread to Toronto, where it was championed by the Toronto Typographical Union. They requested a shortened work week—58 hours, down from as many as 72 hours. The request was turned down. But three years later, the request became a demand backed by the threat of a strike. The demand for a nine-hour day was met with outright refusal by employers, including George Brown, founder of The Globe, who countered that it was “absurd” and “unreasonable.”

On March 25, 1872, the printers went on strike. On April 15, a parade was organized to show solidarity. It started with other tradesmen and a marching band and grew to a crowd of 10,000 (a tenth of Toronto’s population) that marched through the city to Queen’s Park.

As it turned out, union activity was a criminal offence under Canadian law at the time, and police arrested 24 strike leaders. Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, always the political opportunist, quickly passed the Trade Unions Act, which legalized unions and freed the strikers. This had two advantages; it endeared him to working-class voters, and perhaps as importantly, it drove his nemesis George Brown mad with rage.

The Nine-Hour Movement didn’t immediately achieve its goal of a shorter work day. In fact, most of the strikers lost their jobs. But the strike laid the foundation for the Canadian Labour Union, which was formed in April 1873, and because of its size and reach, workers were eventually able to negotiate better conditions.

The parade became an annual tradition, celebrated every spring in Canadian cities. In 1882, American labour leader Peter J. McGuire saw the annual labour event in Toronto, and organized the first American “Labor Day” for Sept. 5 in New York. On July 23, 1894, Prime Minister John Thompson made Labour Day an official holiday and moved it to the first Monday of September.

The Labour Day long weekend has largely lost its connection to the labour movement, but every year on that holiday Monday, as you sit in your deck chair enjoying a cold drink and watching summer wane, you can thank the Toronto Typographical Union.

Advertisement