Private James Munroe Franklin of Hamilton, Ont., is believed to be the first Black North American killed in the First World War. He died near Regina Trench on Oct. 8, 1916. [IWM/Lives of the First World War/7541555]

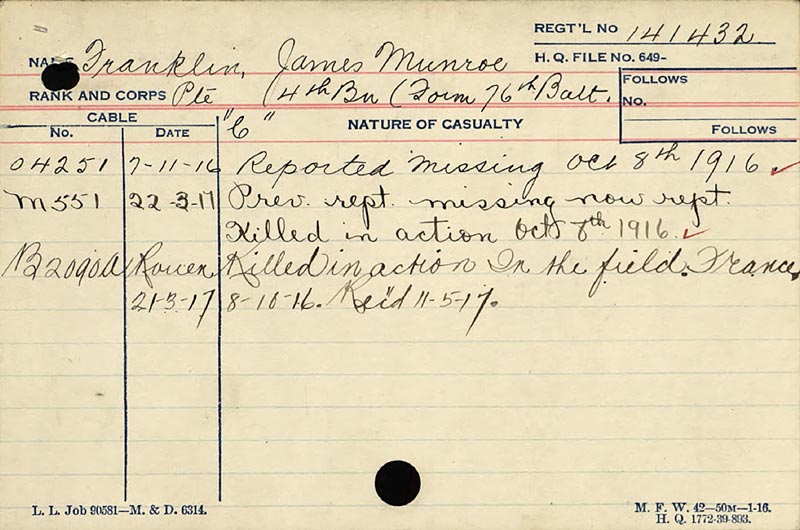

He served in the Ontario-based 76th and 4th battalions and died four days shy of his 17th birthday at Regina Trench during the Battle of the Ancre Heights.

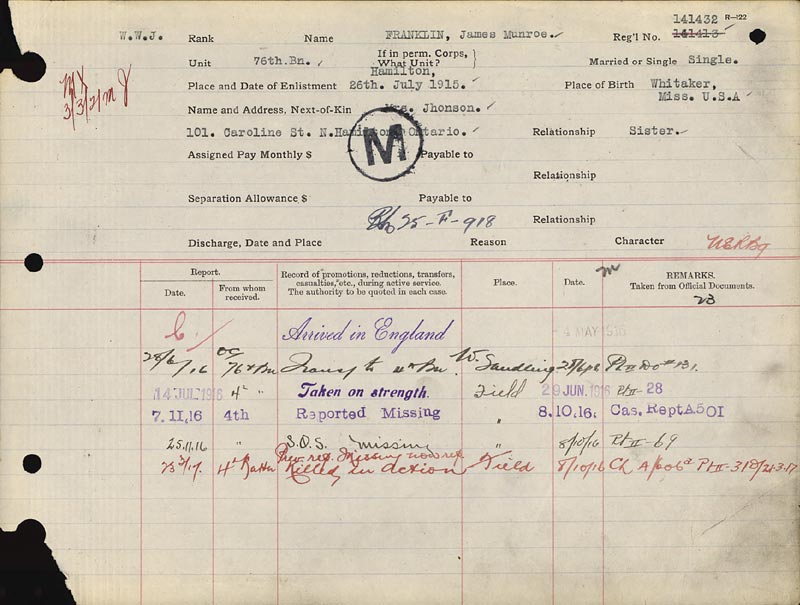

His family left his native Whitaker, Miss., and crossed the Canadian border in 1901, settling in Hamilton, safe from America’s Jim Crow South. He was just seven when his mother Angeline died during pregnancy.

His father, Walter Van Twiller Abraham Franklin, worked as a farmer and an inventor and was credited with inventing the original keyboard chromatic harp. He raised his son a Baptist, but later converted to Judaism and became a rabbi. He put young Franklin in an orphanage.

His dad went on to marry again and father eight more children, but he left Franklin in the Stinson Street Boys’ Home until he was 14, when the boys usually left the harsh orphanage life and went to apprentice with local businesses.

It was 1913, and Franklin found boarding with a local widow named Ellen Henrietta Bryant-Johnston and her children William, Ellen and Charles. Charles was only a few months older than Franklin and they became like brothers.

Franklin found work as a clerk and messenger at the nearby Parke and Parke drugstore, one of Hamilton’s most prominent businesses at the time. It was owned by brothers Walder and George Parke. Walder’s four sons all volunteered as officers in the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

Franklin enlisted under one of the sons, Harold, commander of the 91st Regiment Canadian Highlanders—which may explain why he succeeded where other Blacks could not. Franklin’s attestation papers were signed by Harold Parke as both commanding officer and witness.

It was July 26, 1915, and Franklin—all five-foot-seven inches of him—was just 15 years old. He listed his birth as Oct. 12, 1897, while census records suggest he was born in 1899. His pay was $15 a month.

The 91st was recruiting men for service with the 76th Overseas Battalion at the time. Private Franklin and 76 other soldiers from the 91st, including Harold Parke, were assigned to the battalion’s ‘B’ Company.

They boarded RMS Empress of Britain in Halifax on April 23, 1916, and arrived in Liverpool, England, 12 days later. Franklin was sent to fight in France with the depleted 4th Battalion (Central Ontario) on June 28, three days before the Battle of the Somme began.

The evidence suggests Franklin had already seen plenty of action by the time Canadian units began moving up to the Somme front line in August 1916. The battalion was fighting at Mont. Sorrel near Ypres, Belgium, when he arrived and found themselves in support trenches near La Boisselle, France, on Aug. 31.

At 4:30 a.m., they repelled another German attack.

The 4th moved from village to village from there, pushing back two German attacks by mid-September. At 7:30 p.m. on Sept. 19, German forces launched an assault on the 4th Battalion trenches at Courcelette. Although the village had been taken on Sept. 15, the enemy had secured a foothold after overrunning a Lewis gun position.

The 4th’s ‘B’ Company was called out of reserve to repel what appeared to have been a small raid. But the Germans retreated to their original lines before they got there. The battalion endured heavy artillery fire throughout the night.

At 4:30 a.m., they repelled another German attack and the bulk of the exhausted 4th was relieved a few hours later, down eight officers and 150 enlisted. It set up a battalion headquarters at the infamous Sugar Factory, taken by Canadian troops during the attack on the French village five days before.

The Allies’ attention subsequently turned to the strategic Thiepval Ridge and its network of German trenches, most notable of which was Regina Trench (Staufen Riegel) on the north-facing slope. It was the longest German trench of its type on the Western Front, protected by hundreds of kilometres of barbed wire.

He had been ordered to load up his pack mule and carry combat supplies forward.

It took 41 days of fighting to secure the entire trench. Franklin was killed on Oct. 8 as the Canadians briefly took a portion but couldn’t hold it. Franklin’s unpopular commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel William Rae, wrote in his diary that clearing the German barbed wire had depleted the Canadians’ bomb (grenade) supply.

A supply party took 12 casualties that morning as it brought bombs across open ground. It’s believed Franklin was among them. According to family history, he had been ordered to load up his pack mule and carry combat supplies forward, exposing himself to sniper, artillery and machine-gun fire.“Bombing duels were fought against the enemy throughout the morning,” Andrew Iarocci wrote in his Wilfred Laurier University thesis, The ‘Mad Fourth:’ The 4th Canadian Infantry Battalion at War, 1914-1916.

The attacks grew stronger by early afternoon. Then the Germans launched a massive bombardment.

“Franklin was…the first Canadian of his race to die upon the fields of France.

“It was reported that shells were landing as far back as the Canadian assembly trenches just north of Courcelette,” about two kilometres behind them, Iarocci wrote. “Both the 3rd and 4th Battalions attempted to launch SOS signals, but in every case the signallers were killed before they could deploy the rockets.”

The Chicago Defender, an African-American newspaper, reported Franklin and his mount were “blown to pieces” by a “huge grandmother shell.”

“Franklin was a self-raised, brave young man and the first Canadian of his Race to die upon the fields of France,” the paper said. “This brave young lad, who gave his life that democracy should rule the wide world over, was the only man of his Race in the whole battalion of 2,000 valiant fighters.”

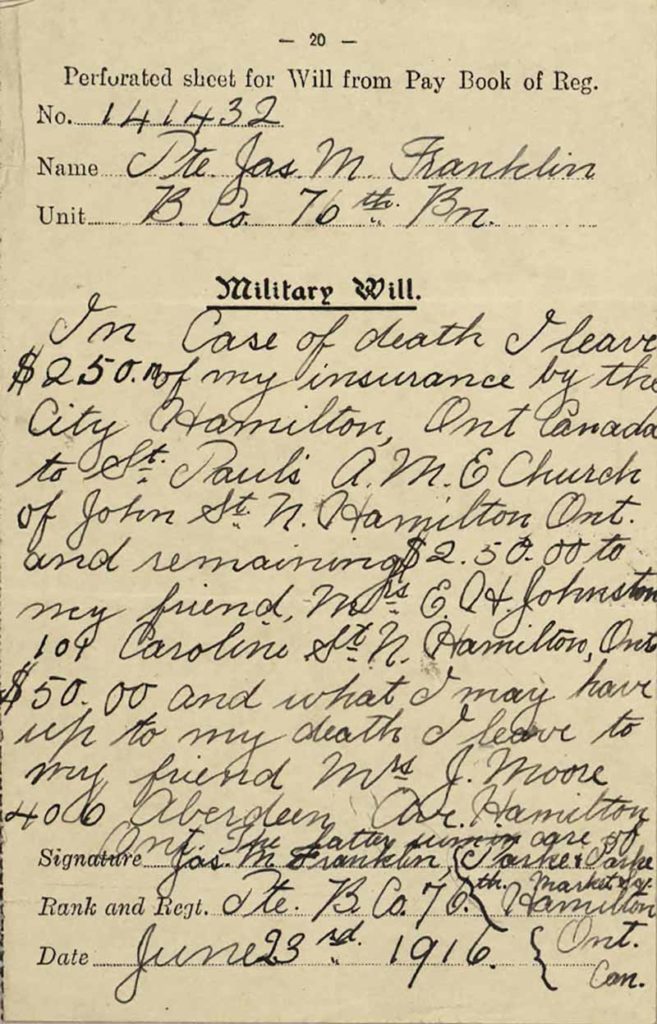

In his will, Franklin left $250 to St. Paul’s African Methodist Episcopal Church in Hamilton, where he had worked as librarian and assistant secretary. He also left $250 to “Mrs. E.H. Johnston,” the woman who gave him a home for two years.

A month later, one of her sons, Charles Bryant, volunteered with No. 2 Construction Battalion, apparently falsifying his age in the process. He sailed overseas on March 28, 1917, and died of meningitis less than four months later.The 4th Canadian Division finally took the western portion of Regina Trench on Oct. 21, repulsing three counterattacks and taking more than 1,000 Germans prisoner. The division took the east end of the trench during the night of Nov. 10-11.

By the time the Canadian Corps was relieved from the Somme front, it had suffered 24,029 casualties, or roughly 24 per cent of the Allied killed, wounded and captured during the four-month battle.

The first largely Black military unit in Canadian history, No. 2 Construction Battalion, had just been formed in Pictou, N.S., on July 5, 1916—four days after the Battle of the Somme began. It was made up of more than 600 recruits from across the country, mostly Nova Scotia. Some even came from the United States.

Historian Kathy Grant estimates 1,300-1,400 Black Canadians served in the First World War, most of them distributed among three segregated units. About 300-400 managed to join regular units and fight on the front lines. Some earned medals. Others, like Nova Scotia’s Jeremiah Jones—who destroyed a German machine-gun position at Vimy Ridge, took prisoners and deposited the captured weapon at his commanding officer’s feet— were denied their due.

After the U.S. declared war in April 1917, some 350,000 African Americans served in segregated units, mostly as support troops. The all-Black Harlem Hellfighters—the 15th New York National Guard Regiment—was the most celebrated Black American unit of the war. Its members confronted racism even as they trained for war in South Carolina, helped bring jazz to France, then battled Germany longer than almost any other American doughboys.

Renamed the 369th Infantry Regiment and assigned to the French, the Hellfighters entered the trenches on April 15, 1918—more than a month before the American Expeditionary Forces fought their first major battle.

The 4th Infantry Battalion with which Franklin died had shipped overseas in October 1914. After it was all over four years later, some 5,563 officers and enlisted had passed through its ranks—about 800 at any one time.

“The Mad 4th” recorded an impressive war record, fighting battles at Ypres (1915); Passchendaele (1917); Gravenstafel; St. Julien; Festubert (1915); Mont Sorrel; Somme (1916); Flers-Courcelette; Ancre Heights; Arras (1917); Vimy (1917); Arleux; Scarpe (1918); Hill 70; the Second Battle of Passchendaele; Amiens; Drocourt-Quéant; Hindenburg Line; Canal du Nord; and the Pursuit to Mons.

Lieutenant J.H. Pedley, who served with ‘C’ Company in 1917-1918, wrote in his wartime memoir that the unrecorded experiences of ordinary soldiers more often than not died with them on the field of battle or faded from memory after they returned to civilian life.

James Franklin has not been forgotten. His name is inscribed on Page 88 of the First World War Book of Remembrance in the Memorial Chamber of the Peace Tower. It is also carved into the Canadian National Vimy Memorial, one of more than 11,000 Canadian soldiers of the Great War listed as “missing, presumed dead” in France.

The Mississippi Armed Forces Museum mounted a temporary exhibit honouring Franklin’s wartime service in 2015.

“Private Franklin’s story is inspirational as an example of loyalty and valour during times of pronounced prejudice and injustice,” said museum director Chad Daniels.

—

Canada and the Brutal Battles of the Somme, the latest in the Canada’s Ultimate Story series, is on newsstands now. You can also order it for delivery to your home from the Canada’s Ultimate Story website.

Advertisement