The Mace of Upper Canada became a prized war trophy of American Brigadier-General Zebulon Pike after he defeated British General Roger Sheaffe at the Battle of York in April 1813 .[Wikimedia; Legislative Assembly of Ontario; Wikimedia/Royal Museums Greenwich; Owen Staples]

During the War of 1812,” declared U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt on May 4, 1934, “the Mace of the Parliament of Upper Canada, or Ontario, was taken by United States Forces at the time of the battle of York, April 27, 1813. That Mace, which had been the symbol of legislative authority at York (now Toronto) since 1792, has been preserved in the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis.”

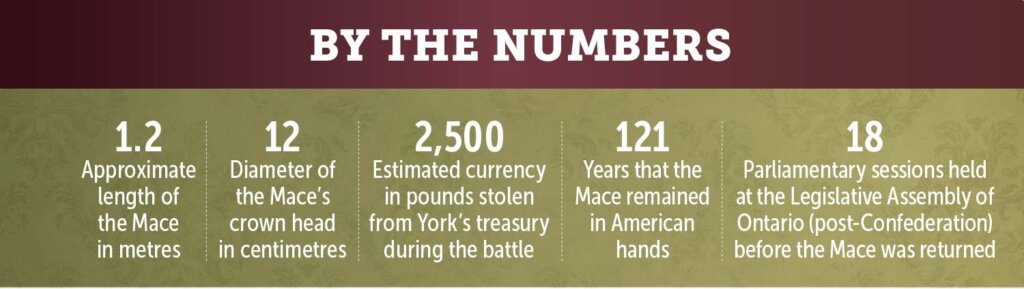

Made from soft wood, perhaps fir or pine, and measuring 142 centimetres long (4′8″), the centuries-old Yankee plunder was, despite its symbolic value to Anglo-Canadian governance, deemed primitive in appearance. Chroniclers often described it as gilded and decorated red in parts; but, it was merely painted gold.

However, in seizing it on that fateful April day, explained Ewan Wardle of the Fort York National Historic Site, “the soldiers and sailors of the young [U.S.] republic were snubbing the majesty of the Crown—of King George III himself.”

Maces were once a favoured weapon of the Middle Ages, especially Medieval-era martial bishops who, bound by canonical law, couldn’t use blood-letting arms such as swords. A club, therefore, could honour oaths to God while providing clergymen with a suitable defence against helmeted and armoured opponents.

As early as the 13th century, maces took on ceremonial reverence, later evolving into symbols of legislative authority for speakers of the British parliament and, ultimately, starting in the 18th century, within the British Empire’s Canadian colonies.

By 1813, the Mace of Upper Canada resided in York after the provincial capital moved from Newark (modern-day Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ont.) in 1796.

In York, having travelled across Lake Ontario aboard an estimated 14 ships, a force of some 2,700 American soldiers and sailors began their April 1813 attack.

The numerical superiority of the invaders, commanded by Brigadier-General Zebulon Pike, against British General Roger Sheaffe’s 700-strong defence quickly became apparent. For the Canadian militiamen, Mississauga and Ojibwa warriors, and 300 dock workers protecting York, it was clearly a lost cause.

Prior to torching York’s government buildings, several symbolic items, including the mace, became spoils of war.

And British resistance at Fort York couldn’t stem the tide. Realizing the hopelessness of the circumstances, Sheaffe ordered a retreat to Kingston—but not before setting alight a gunpowder magazine.

The ensuing explosion killed Pike, who died with his head resting on a captured Union Jack. Infuriated, the Americans and their Canadian sympathizers started razing the town.

Some 2,500 pounds was also stolen from the treasury; dismantled parts of the warship Duke of Gloucester were captured; and, prior to torching York’s government buildings, several symbolic items, including the Mace, became spoils of war.

The British had their revenge by burning Washington, D.C., the following year, but Upper Canada’s legislative regalia stayed in the U.S. for 121 years, until July 4, 1934, coinciding with the unveiling of a memorial in Toronto dedicated to American losses at the Battle of York.

“Since the agreement of 1817,” said Roosevelt earlier in urging the return of the plundered artifact, “the two countries have…maintained no hostile armaments on either side of their boundary; and every passing year cements the peace and friendship between [their] peoples.”

Although previously replaced—indeed, more than once—the Mace of Upper Canada is now displayed at the Legislative Assembly of Ontario in Toronto.

Advertisement