Nursing Sister Sarah Persis Johnson and her brother, Pte. James Willis Johnson, did the family proud during their First World War Service.

[Glenbow Archives; Johnson family archive]

Born in County Cork, Ireland, and raised in rural Manitoba, Private James Willis Johnson and Nursing Sister Sarah Persis Johnson both enlisted with the Canadian Expeditionary Force shortly after war broke out in 1914. He was 22. She was 28.

A cavalry trooper, James was wounded soon after he reached the front in 1915. He would survive a six-month recovery process and go on to earn the Commonwealth’s second-highest award for valour.

His sister, who went by Persis, or Persie to family and friends, had earned a gold medal on graduating from the nursing program at Manitoba’s Brandon General Hospital in 1911.

She went on to earn a post-graduate degree in nursing in Chicago, then left her job as assistant matron at Brandon General to join the Nursing Sisters of the Canadian Army Medical Corps in September 1914.

Both were good writers.

“Sometime in March, I am lost on dates, the Boche sent so many shells around our camp that at half an hours notice we were sent to St. Omer, very much against our wishes and very unhappy,” Persis wrote home on May 13, 1918.

She was serving with 2nd Canadian Casualty Clearing Station (CCCS) near the front around the Ypres Salient in Belgium, where Allied forces had stopped the German push to the sea and the Channel ports of France.

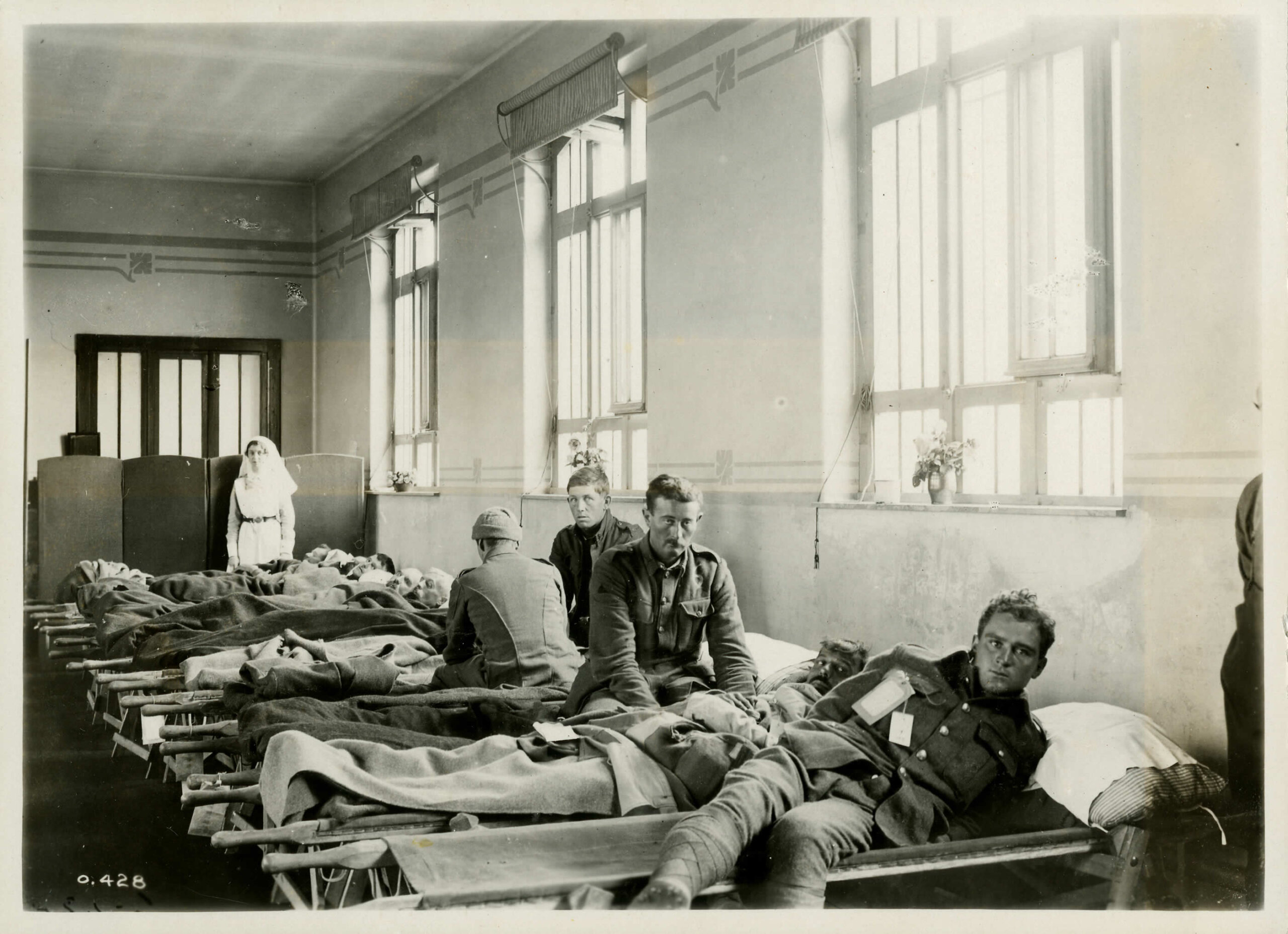

Clearing stations were the first stop on a wounded soldier’s journey back from the front. When the fighting was at its peak, they would handle hundreds of casualties a day, usually with a patient survival rate of more than 95 per cent.

“Now I hope all this won’t make you worry for you can rest assured I’d rather be where I am than anywhere,” she wrote, “and bombs etc. don’t bother us at all—they often fall around but often fall wide of the mark and I think it is not intentional when they hit hospitals.

“That sounds like a great big ‘I’ but I don’t mean it to be. I suppose I am being childish full of it all. Our soldiers are splendid and the salt of the earth. I do hope you will all be kind and patient and charitable to those who return for we all owe them a debt we can never repay. The world is full of rough diamonds.”

The following September, Persis was awarded the Royal Red Cross, Second Class, for exceptional service in military nursing. The RRC was first awarded to the founder of modern nursing, Florence Nightingale, in 1883.

Persis would accumulate an outstanding record serving in wartime hospitals in England, field hospitals in France and Belgium, and casualty clearing stations all over, including postwar Germany. By war’s end, she was matron of 1st Canadian Casualty Clearing Station and received the Royal Red Cross, First Class, from the Prince of Wales himself.

“The next thing I remember after hearing it coming is crawling out of the mud with blood running down my neck.”

At 4:55 p.m. on Dec. 8, 1915, James was with the 1st Regiment, Canadian Mounted Rifles (CMR), in Rossignol, 260 kilometres southeast of Ypres, where French and German forces had fought one of the first battles of the war back in August 1914.

The dismounted Canadians and their German opponents had been exchanging artillery fire for days. Now James (Jim to friends and family) was standing on the bank of the River Douve, watching Allied shells bursting over German lines. The enemy had been returning fire toward 3 CMR to his right, wounding five troopers.

“Well, all of a sudden they switched their fire back to where I was,” he wrote his sister Ethel from Ward 2, Moore Barracks Hospital in Shorncliffe, England, on Valentine’s Day 1916. “The first one splashed in a pool about fifty yards to the rear.

“The next one—a fine, healthy nine-inch shell—just came over the parapet to the right of me and burst in a dugout just behind me.

“The next thing I remember after hearing it coming is crawling out of the mud with blood running down my neck.”

James had shrapnel wounds to his head, neck and feet. According to the unit war diary, an officer was killed and another wounded in the barrage, along with six enlisted.

An aspiring farmer, James had been at or near the front for most of the time since he saw his first action in September. Now he was headed for six months in and out of hospitals in France and England.

“I was moved up here on Saturday last and on Sunday I was surprised to see Persis walk in,” he wrote.

Lieut. Harcus C. Strachan, VC, leads his squadron of the Fort Garry Horse through a village on the Cambrai front in 1917.

[LAC]

After her brother returned to the fighting as a member of The Fort Garry Horse, Persis would speculate in letters on where he might be or where she had heard he had been. On May 19, 1918, she wrote that James “is well and I think is at AIRE.”

James was a sergeant with the Fort Garrys by the time he led a small patrol onto a machine-gun nest at Beaucourt in northeastern France, less than 200 kilometres from the Swiss border.

He had been promoted twice and awarded a good conduct badge in 1917. But in the summer of 1918, weeks after he landed his third promotion in less than a year, he contracted influenza. He was admitted to hospital on July 20, 1918, and managed to return to his unit in a week.

Twelve days later, he engineered the action that would define his war.

The regimental war diary describes the capture of the village of Beaucourt and the costs: 12 wounded and 35 horses killed, wounded or missing.

“A number of prisoners were taken.”

Indeed, 11 of them were Johnson’s, earning him a Distinguished Conduct Medal for “conspicuous gallantry and enterprise.” Created during the Crimean War and first awarded to a Canadian in 1901, it was second only to the Victoria Cross in the Empire’s order of valour.

“After the Squadron had seized the village of BEAUCOURT, Sgt Johnson located a party of enemy with machine guns in the church who were causing casualties to the Squadron,” reads Johnson’s citation in the London Gazette of Oct. 30, 1918.

“This NCO with a picked patrol attacked enemy’s position and by clear and courageous action, succeeded in capturing 11 prisoners and one machine gun.”

Two days later, on the morning of Aug. 10, the regiment moved forward. The troopers would come under heavy artillery and machine-gun fire, suffering casualties to four officers, 41 enlisted and 112 horses.

“Due to the serious nature of the casualties received, the death rate has been high.”

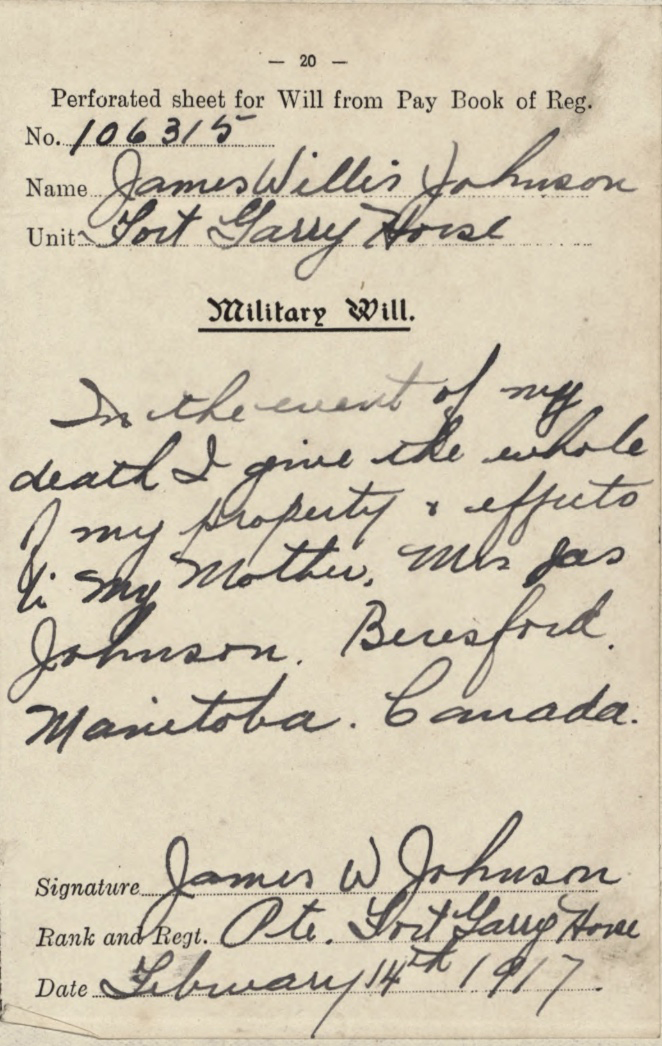

James Johnson’s last will and testament left everything to his mother. He came close, but he wouldn’t need it.

[LAC]

All were volunteers and there was never a shortage of candidates. In January 1915 alone, there were 2,000 applicants for 75 positions.

In many cases, a Bluebird was the last face a Canadian soldier would ever see—an angel from above.

Of the 2,845 Canadian nursing sisters who served, at least 58 died. Twice in 1918, Canadian army hospitals in Europe were bombed and several nurses killed. On June 27, 1918, a U-boat torpedoed and sank the Canadian hospital ship Llandovery Castle. All 14 nurses on board died.

“If all concerned realized as we do it would soon end,” Persis wrote in the last year of the war, “but as it is some people are still playing about and taking things as a matter of course. If they don’t wake up it is certain we will have to make many more sacrifices before it ends.”

Persis left 2 CCCS and served a stint with 3 Canadian General Hospital before joining 1st Canadian Casualty Clearing Station in October 1918. Canadian shock troops were spearheading the 100 Days Campaign. The war would soon be over.

No. 1 Canadian Casualty Clearing Station somewhere on the Western Front.

[CWM/19920044-385]

Most diary entries were made by the station commander, but in the busy month of October 1918, the last full month of the war with the unit moving in concert with the Canadian advance, Persis Johnson recorded some of the doings of 1st Canadian Casualty Clearing Station shortly after she was appointed acting matron.

“Due to the serious nature of the casualties received, the death rate has been high,” she wrote on Oct. 30 (in fact, 48 of 993 admissions died, a 95 per cent survival rate).

“A number of French civilian women and children patients who are being cared for in a building nearby by the 14th Can Fld Ambulance are being visited by our sisters twice daily or as often as necessary.”

On Nov. 11, the station was “very busy” despite the fact the war had officially ended at 11 a.m.

“Receiving steadily and overflowing into neighbouring buildings,” wrote the officer commanding, Lieutenant-Colonel A.E.H. Bennett. “Many flu cases and bronchial pneumonia. The war was not over as far as we were concerned.

“One patient claimed to be wounded at 11:10 a.m.”

Persis was one of four staff to represent the clearing station at the official entry into Mons, Belgium, the last stop for the fighting Canadians.

The Distinguished Conduct Medal (left) and the Royal Red Cross, First Class.

[GOC]

Johnson’s fighting days were all but over. He would return to Canada in 1919, marry Lillian Boberg, and build a life farming and raising a family near Eston, Sask. He died in 1984. He was 91.

Sarah Persis Johnson Darrach was named a member of the Order of the British Empire (Civilian) for her tireless charity work.

[N/A]

In 1934, she was named a member of the Order of the British Empire (Civilian) for her tireless charity work. In 1936, she became dean of women at Brandon College, where she served until 1953. In 1971, Brandon University awarded her an honorary doctor of laws degree.

Darrach Hall—the men’s residence on the Brandon University campus—and Darrach Avenue were named in her honour. Sarah Persis Johnson Darrach died in 1974, age 88.

James O’Brien (Jamie) Johnson with his grandad James Willis (Jim) Johnson and his father James Victor (Vic) Johnson in 1980.

[Johnson family archive]

Advertisement