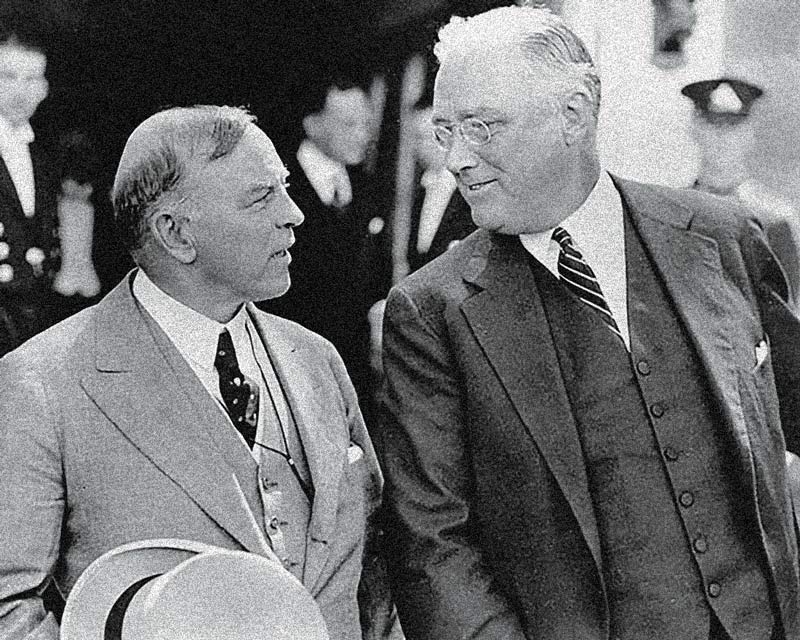

Prime Minister Mackenzie King and U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt chat during a 1936 meeting in Quebec City. [LAC/C-016768]

While Canada would become one of the U.S.’s most steadfast allies in the Second World War—and was already its number one trading partner by the 1920s—Americans have often taken Canada for granted. Perhaps that is typically the case with good neighbours. And yet trade deals, diplomatic relations, and military alliances take work: hard as they are in times of peace, they are harder still during wartime, when nations have their way of life imperilled and there is little time to formulate plans.

Major-General Maurice Pope, an experienced soldier who was a key Canadian officer in wartime Washington, wrote of the challenges he faced in dealing with the Americans and standing up for the Dominion. It was never easy, he wrote, and one always ran the risk of being “big-sticked.” This was a reference to President Theodore Roosevelt’s intimidating phrase from the early 20th century, in which he advocated for “speaking softly, and carrying a big stick” for possible use in bludgeoning Canadians into accepting American demands.

“We shall not be a burden on anyone else—neither a burden on the States nor a burden on England,” said Prime Minister Mackenzie King before the war. He lived up to that promise. The Canadian and American joint effort to fortify the nations’ shared frontiers may be the most successful alliance ever forged by the U.S. in terms of both ease and resources expended for ultimate gain.

The Canadian and American joint effort to fortify the nations’ shared frontiers may be the most successful alliance ever forged by the U.S.

Great War-era American tanks arrive in Canada early in WW II, a sign of U.S. support of the country’s war effort, as materiel production ramps up.[Courtesy Tim Cook]

In the context of prosecuting the war against the Axis powers, the U.S. had a more important wartime alliance with Britain than with Canada, but it was the relationship with the Dominion that was critical for defending North America. The Soviets—one-time enemy turned untrustworthy co-belligerent—were a different breed of ally. They had to be propped up with billions of dollars in aid and military equipment, as it was understood that if the Communists had not been bleeding the Nazis dry through bitter fighting on the Eastern Front from June 1941, there would be little hope of the war ending in anything other than a negotiated peace with Hitler in control of Europe.

Though Canada was never a great power, and stayed clear of the responsibilities and challenges that are required of such nations, it emerged during the war—and because of the war—as a wealthy country better able to exploit its natural resources, harness its industry potential and fulfill security obligations. It did so because it had largely shed its colonial past to act as an independent nation, turning to the U.S. even as it strove to stand with Britain in facing the Axis powers.

In a time of great destruction, the alliance between Canada and the U.S. was nothing short of astonishing.

Canadian and U.S. troops take in a baseball game in Britain during WW II.[Courtesy Tim Cook]

Though much energy has been directed toward exploring Canada’s military effort overseas, far less has been spent examining the defence of North America. It is a story that mattered from 1939 to 1945, and one that continues to offer lessons to this day. At the same time, most Canadian wartime histories are centred on the Canadian and British experience—not surprisingly, since the Canadians most often served with Imperial forces.

Ties of kith, kin, history, politics, and culture also cemented this focus. Despite its historic role in aiding the Canadian war effort, the U.S. has rarely been the focus of a comprehensive study that examines defence, security, culture, economics, trade, politics and diplomacy. And, so, The Good Allies shifts the gaze from the east-west axis of the transatlantic toward the north-south partnership over the border, providing a new way to understand the Canadian war effort and its profound legacy for the development of the country.

The discussion here is weighted firmly toward the Canadian war effort from a Canadian perspective. Tens of thousands of books have been written about the American experience of the war, from the standpoint of both participants and historians over several generations, and almost all neglect Canada and its considerable contributions to the Allied victory. Some of that blindness is due to the scope and breadth of the American martial mobilization; some of it too is because Canada was a dependable ally and much determined effort was made to ensure the wartime machinery worked smoothly between the two nations.

Historical analysis is often drawn to crisis and conflict, and there was little of that in the profitable Canadian-American alliance. Some of the responsibility for our absence from the American historical record also rests on Canadians. Much of the literature related to North American relations is coloured by the fear of a postwar loss of independence, especially from the 1960s to the end of the century. The countries’ relationship during the Second World War does not fit easily into that literature of grievance and anxiety.

The Good Allies shows that Canadians and Americans served together to safeguard North America, and that once it was protected from invasion and had its defences built up, they jointly took the war to the fascists overseas. At home, during the period of the United States’ neutrality, Canada’s rearmament programs on the two coasts were often driven by the need to convince the Americans that the Dominion was secure against incursion by a foreign power.

“To the Americans the defence of the United States is continental defence,” warned one senior Canadian general, noting that this included Canada, with or without its leaders’ consent. “What we have to fear is more a lack of confidence in the United States as to our security, rather than enemy action.”

Canadians were acutely aware of the hazard at stake if the southern behemoth felt its northern border was exposed. The King government wished to give the Americans no reason to feel they needed to liberate their neighbour from an invading force, for he worried the U.S. soldiers might not leave after the crisis. Canada would struggle throughout the war to ensure its sovereignty was respected by the republic to the south.

Though a cross-border invasion by the U.S.—even one to liberate Canada from a German or Japanese invasion force—was an unlikely scenario, Ottawa had to plan to avoid any such threat. The first fruit of this initiative was the promotion of mutual co-operation and military support between Canada and the U.S. On the east coast, Canadian naval and air forces wrestled with the German U-boat threat and led essential convoys across the Atlantic to bring war supplies to a besieged Britain. Even before the Americans formally came into the war on the side of the Allies, the U.S. navy was assisting in the war at sea.

That action came from Roosevelt, who, as commander-in-chief of the U.S. armed forces, slowly positioned his nation to fight, citing his obligation to protect America’s coast. Indeed, in February 1942, the president watched in desperation as the Axis powers were winning on every front. He described the struggle as being “different from all the other wars of the past,” and predicted it would determine the “survival of our civilization.”

After the Japanese attack against the West on Dec. 7, 1941, Canada and the U.S. were drawn closer together, with the Royal Canadian Navy assisting the Americans along the North American east coast as enemy U-boats savaged their shipping. In the West, Canada strengthened its defences to reassure the Americans and jointly protect the long coastline, sent military formations to Alaska to stand with their allies, and even participated in a combined invasion of the Japanese-occupied Kiska Island in August 1943.

These actions were done despite Canada having lost much of its influence with the U.S. after Britain pushed the Dominion aside to have closer relations with the Americans. Led by Prime Minister Winston Churchill, the British worked in a bilateral relationship with the Americans, anxious not to have Canada present, which could dilute Britain’s voice, but equally eager to continue to draw upon the Commonwealth nation’s considerable military and economic resources. In early 1942, Prime Minister King complained that when the two great leaders were in conversation and jousting with one another, it “crowd[ed] both Canada and myself off the map.”

Canada did not withdraw in a sulk. The nation’s politicians, diplomats and service personnel shored up defences, worked with their American counterparts, and continued to fight abroad. While the country’s people were galvanized to victory on farms, in mines, and from the factory floor, Canadian officials conducted the delicate dance of assisting Britain by forging closer ties with the Americans.

In dealing with both Britain and the U.S., the Canadians grappled with exerting their sovereignty, with no area more problematic than the North, where the Americans insisted on building the Alaska Highway and air staging routes to support Alaska. Even with more than 30,000 foreign soldiers and workers operating on Canadian soil, the Canucks remained accommodating allies, willing to swallow their fear of the concentrated U.S. presence.

That did not mean there was no worry as Ottawa navigated this new relationship and learned how to stand up for itself. Robert G. Riddell, an astute observer in the Department of External Affairs, wrote in February 1943, “[W]e

are letting the Americans get away with things that would have broken the Commonwealth in little pieces if London had tried them.”

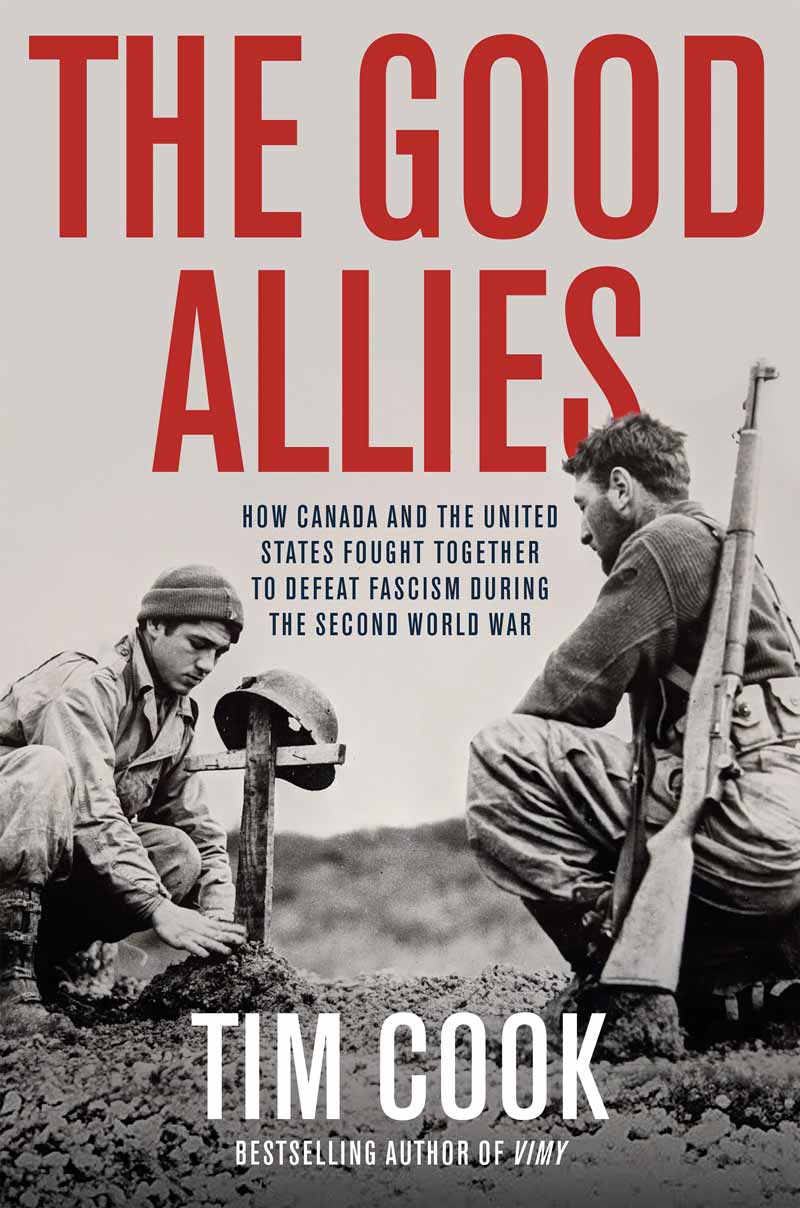

Excerpted from The Good Allies by Tim Cook. Copyright © 2024 Tim Cook. Published by Allen Lane, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved.[Courtesy Allen Lane, a division of Penguin Random House Canada]

With North America secure from enemy attack by 1943, the Canadians and Americans took their co-operation overseas, fighting side by side in Sicily and mainland Italy. This partnership found its culmination in the First Special Service Force, a unique unit consisting of Canadians and Americans. In the air war over Europe, North American bombers, often operated by crews made up of “New World” airmen, struck Germany.

At least 30,000 American volunteers served in the Royal Canadian Air Force and the Canadian Army. The multi-pronged war against the Nazis culminated in the great crusade for Europe, starting on June 6, 1944. Canadian, British, and American forces landed on D-Day, clawing their way forward in that enormous military operation to liberate the French and other oppressed people. This dangerous landing, and the grim combat to follow, was a visible demonstration of that three-way partnership.

In the Pacific, Canadians and Americans rarely fought together, although 10,000 Canadians were stationed in that geographic theatre of war, and more would have served if the war had extended into 1946. Even more important, more than three million Canadians were engaged in home-front war industry work, mineral extraction and food production, all of which involved deep collaboration with the American war effort, revealing that the good allyship went both ways.

The massive production of weapons and vehicles pulled the Dominion from the mire of the Depression years and gave it immense resources that it directed most forcefully toward supporting Britain in its desperate battles. Sometimes the relationship between the North American nations was antagonistic, but more often it was based on mutual goals. Flying in the RCAF, New York state native Malcolm Hormats recalled that his service “left [him] with a profound respect and admiration for Canadian flyers in particular and Canadians in general.”

Many Americans felt the same way.

In a time of great destruction, unimaginable slaughter, and genocidal actions against the people of neighbouring nations, the alliance between Canada and the U.S. was nothing short of astonishing. Both the heroic and the ordinary are covered in The Good Allies, including presidents and prime ministers, generals and admirals, but also service personnel, war workers and civilians on the home front.

Training its focus on the history of war both in North America and beyond its borders, the narrative shifts from the strategic to the operational level and then percolates down to units and individuals. Victory would not have been possible without the Canadian and American relationship based on a common cause: to liberate the oppressed and destroy fascism.

Advertisement