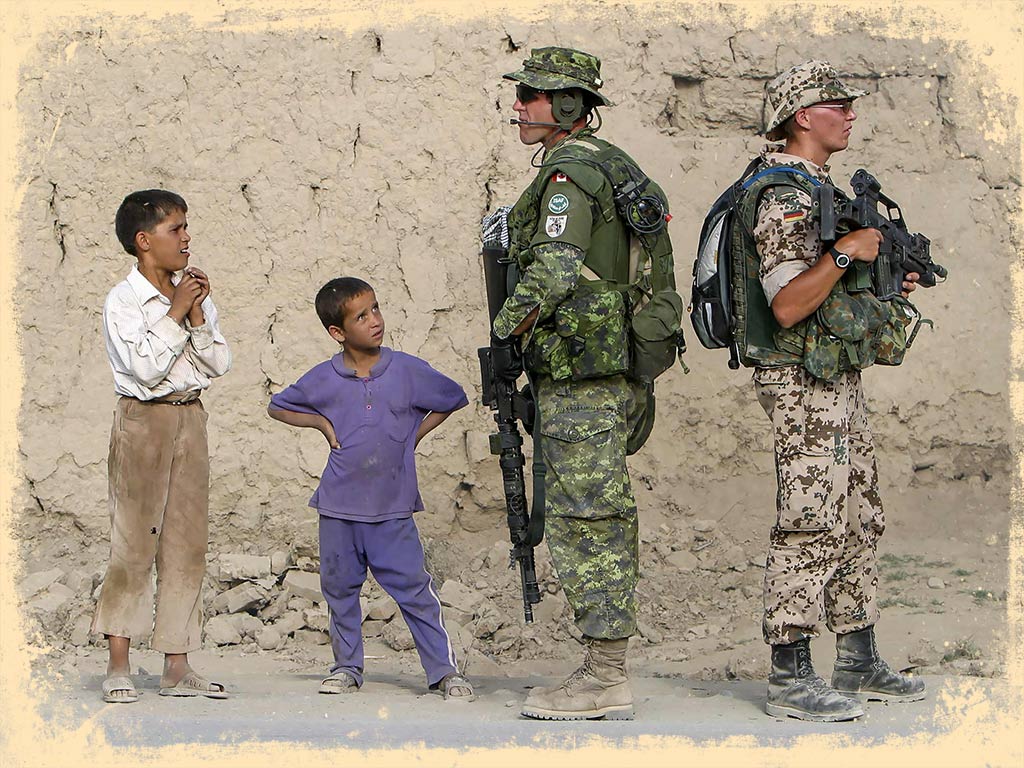

Canadian soldier in Afghanistan [Stephen J Thorne]

There’s a swing bridge, and all they tell you to do is walk,” said retired master corporal Mike Trauner. “Just walk in a straight line across the bridge.”

Beginners, he explained, have only a light breeze rocking the flimsy span back and forth. “But for me…the bridge is just swinging wildly out of control.”

Trauner, an Afghanistan combat veteran who uses prosthetic legs—the result of two improvised explosive devices detonating under him on Dec. 5, 2008—recalled grabbing the handles to gain stability before pushing on.

Yet despite the almighty gusts, despite the swaying structure and despite the seemingly perilous risk of falling, he remembered being unafraid.

The bridge, in reality, never truly existed. Nor did the wind.

But in Trauner’s case, alongside other Canadians who returned from Afghanistan with life-changing wounds, the so-called Caren (Computer-Assisted Rehabilitation Environment) system has brought—and for some still brings—a virtual reality capable of producing tangible results.

One of only two such facilities in Canada, The Ottawa Hospital’s Caren lab has, since being installed in 2010 in partnership with the Canadian Armed Forces, enabled patients to push boundaries in a safe and controlled setting.

The technology, monitored by a collaborative team of rehabilitation experts, psychologists, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, researchers and more, encompasses an entire room dominated by a large projection screen. A moving platform, which can tilt in different directions depending on the patient’s movements, and a remote-controlled treadmill add to the immersive experience as participants are secured in a harness attached to a fall-restraint system.

“It allows us to simulate so many different environments besides flat-level ground walking,” explained Dr. Nancy Dudek, medical director of the hospital’s amputee program. “It likewise affords a great degree of comfort knowing that if it doesn’t go as planned, [the patient] is not going to sustain injuries.”

Considered an accompaniment to other aspects of the rehabilitation process, the virtual reality program captures data that medical professionals can assess and adapt according to the patient’s needs. Its scope, meanwhile, can reach beyond combat-related wounds to the likes of traumatic brain or spinal cord injuries, neuromuscular disease, mental health conditions or chronic pain.

“The Caren system can be just as beneficial to, say, a 28-year-old who happened to be in a civilian motor accident as to a 28-year-old member of the Canadian Armed Forces wounded in the field,” said Dr. Dudek.

And then there are the scenarios themselves, which can cater to individual circumstances, goals, interests and requirements. While some, such as traipsing across a rickety bridge, bear an arguably closer resemblance to fantastical video games, others draw inspiration from everyday life.

A three-dimensional map of downtown Ottawa is just one example, where crowds throng the streets, vehicles drive by and obstacles can spontaneously present themselves. “The idea is to give [patients] mental challenges, which is what happens in the real world when somebody walks in front of you or you have to suddenly move,” noted Dr. Dudek.

Another, Trauner recalled, placed him on a boat. Here, balance and weight dispersal become critical as patients navigate around a series of buoys, all the while building confidence in their abilities and those of their prosthetics.

Bushra Saeed-Khan also remembered cruising over virtual waters during her rehabilitation. On Dec. 30, 2009, the 25-year-old

Canadian diplomat was only eight weeks into a one-year assignment when her light-armoured vehicle encountered an improvised explosive device near Kandahar.

“There were 10 of us [in the vehicle]. Five of us passed away immediately, and five of us survived,” explained Saeed-Khan, whose wounds resulted in the loss of a leg, while the other was severely damaged.

By the time she arrived at the rehabilitation centre in Ottawa, Saeed-Khan’s recovery had extended beyond the physical and into mental barriers.

“I was still knee-deep in my rehab and surgeries…for the first few months,” she said, “until I reached a point where I almost felt I started to stagnate a bit. I wanted to go back home and back to work. But there was still this fear of being back in the community because I was so comfortable in the rehab centre. It was accessible, it was safe.”

The Caren system helped her push physical boundaries.

The program’s importance to mental health, as Saeed-Khan herself recognized, cannot be overstated: “It took me a few efforts to trust the Caren system. But it helped me figure out what was possible and what was not.”

Whether walking over uneven ground in a virtual forest or steadying herself on a virtual bus, each accomplished task brought Saeed-Khan closer to the life she hoped to lead. Even when specific scenarios—and their varying difficulty settings—posed challenges beyond her new circumstances, the diplomat remained grateful for the clarity that came with knowing her limitations.

One of Saeed-Khan’s long-term goals, however, posed an entirely different challenge with a unique set of considerations: motherhood.

“Not only did I want to physically have [children] if possible,” she said, “but just play with them and engage with them. Everything I did at the rehab centre, every surgery, every exercise, I wondered how it would affect that.”

Beyond the rehabilitation lab, trials and tribulations awaited Saeed-Khan over the subsequent years as the prospect of pregnancy was complicated by her past wounds. Nevertheless, in 2018, she and her husband welcomed their daughter into the world. More recently, Saeed-Khan gave birth to a son.

“They’re like mini Caren systems,” she joked of her five-year-old and two-year-old children. “They’ve just got to push you sometimes.”

In part due to her virtual reality journey, together with The Ottawa Hospital’s dedicated team that helped her along the way, Saeed-Khan eventually returned to work. She is currently posted to the UN in New York.

Trauner’s sporting career continues to flourish. In 2023, the veteran served as games ambassador at The Royal Canadian Legion’s National Youth Track and Field Championships, a position he will take on again in 2024.

“I think the military made me the person I am today,” said Trauner. “But ultimately, in a way, the Caren system fine-tuned me.”

Advertisement